Chairman's Blog

On cancelling Christmas

|

| Sung Midnight Mass (anticipated at 6pm) in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford. Despite everything it will take place again this year. |

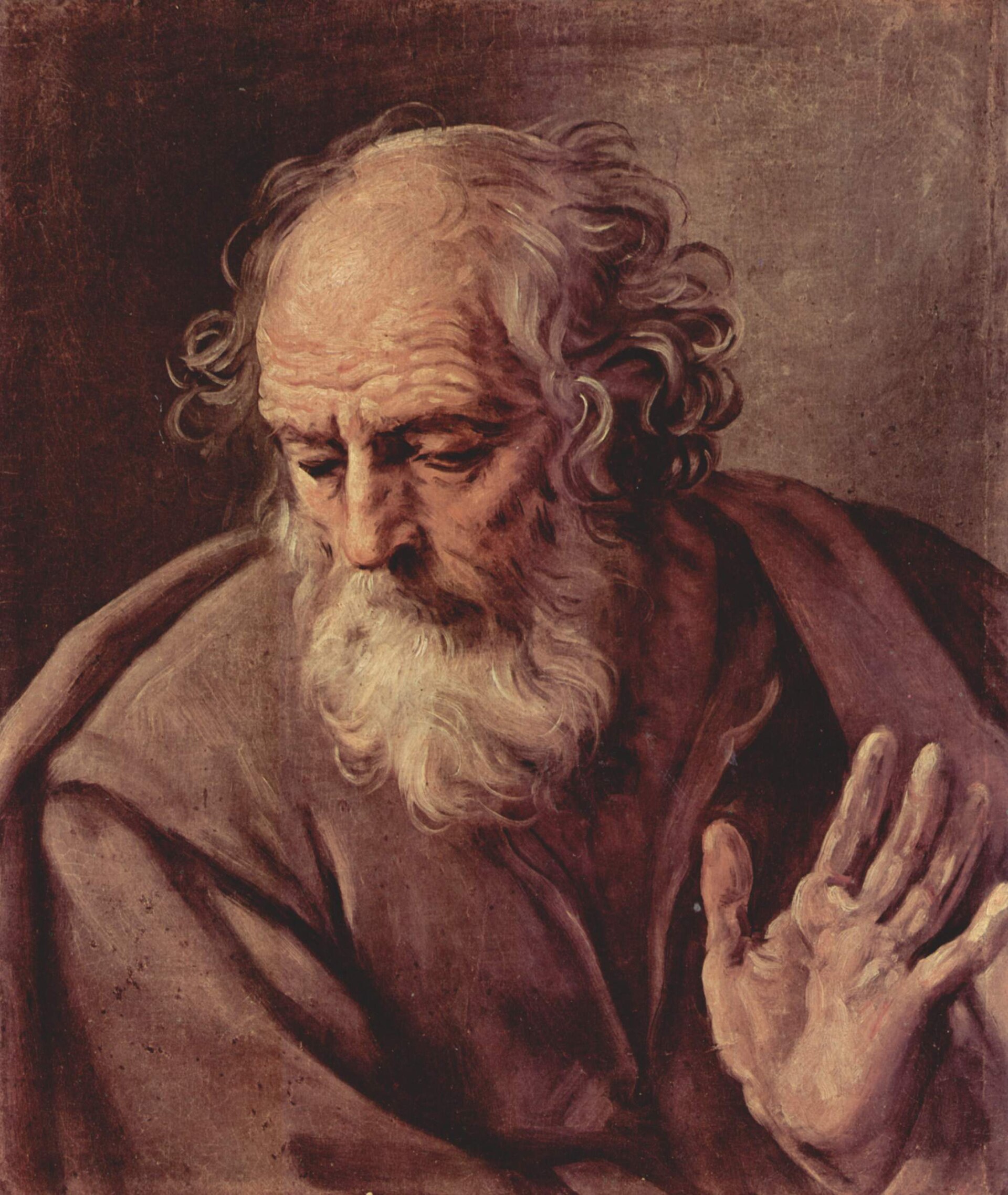

Thoughts sparked by Joseph Sciambra

|

| St Joseph, from Wikipedia Commons |

Read my whole article.

Support the Latin Mass Society

Meet Fr Joseph Quigley, creator of Catholic sex education and paedophile

This story, as they say, writes itself. Fr Joseph Quigly, author of the Birmingham Archdiocese's first foray into sex education, All That I Am, explained about it:

"If we talk about sexuality as a gift, clearly we want to introduce them to that at an appropriate level."

Who could possible have imagined that a man who made it his mission to destroy the innocence of children, who planned, designed, imposed and defended the systematic breaking-down of the natural sexual reserve of nine-year-olds -- who could have possibly thought for a moment that such a man might be sadistic paedophile? I suppose we should all have complete confidence that such an astonishing coincidence is just that -- a coincidence -- and that no-one else involved in the demonic project to sexualise our children is also involved in the demonic project of physically abusing them. Because to connect the two things would be ridiculous wouldn't it? No, it would be far more sane to agree with the sex education establishment that to sexualise children in the classroom is actually a protection against sexualisation by paedophiles. In some way they will I'm sure explain very clearly.

Me on LifeSite.

Father Joseph Quigley of the Archdiocese of Birmingham, England was convicted this week of sexual activity with a child, sexual assault, false imprisonment (he liked to lock children in a crypt) and cruelty. One case against him dated from the 1990s, another concerned his actions between 2006 and 2008.

The Archdiocese, headed until 2009 by Vincent Nichols, now the Cardinal Archbishop of Birmingham, and since then by Archbishop Bernard Longley, failed to report Quigley to the police when they learned of one set of his crimes in 2008. Instead, they flew him to the United States for “rehabilitation” in a specialist clinic and subsequently allowed him to return to work in the UK.

After that, he was supposedly under “restrictions,” but managed somehow to celebrate Mass at a school in 2009, and he was commissioned by the Archdiocese to carry out a school inspection in 2011.

What were they thinking? Well, as a matter of fact, Quigley supposedly had considerable expertise in education. If he had been diagnosed as a “a sexual sadist and voyeur,” what did that matter? Let me quote the report in the UK’s liberal Catholic weekly, The Tablet.

At the time that the first allegations against Quigley were made in 2008, he was both director of education for the Birmingham archdiocese and national adviser on religious education for the Catholic Education Service (CES), of which Archbishop Nichols was chair. …

That Natvity scene in the Vatican

Me on LifeSite.

This year, the annual tradition of the large-scale Nativity scene in St Peter’s Square descended into farce when the figures were revealed as childish and hideous products of artistic modernism. The figures were produced over the course of about a decade starting in 1965 and are reminiscent of the mediocre art of that time. One of the figures visiting the crib is an astronaut; others are unrecognizable. There is an angel represented as a bizarre, tower-like object with meaningless rings round it.

There are a great many reasons why this collection of objects is unsuitable for display as the Vatican’s Nativity scene. I leave it to art historians to decide whether it has sufficient historical importance to gather dust in a provincial museum somewhere. If it were not the season of goodwill, I might suggest it be crushed and used for road-building. But the simple and overwhelming point to make about it is that while it might claim to be religious art — art inspired by religious themes or values, or representing a scene with religious significance — it cannot possibly be described as devotional art.

The failure to distinguish these two categories is to blame for a lot of en

tirely inappropriate art in our churches. Consider the images showing the Stations of the Cross. These are designed to assist the user (and, yes, devotional art is used), to enter imaginatively into the scenes of Christ’s sufferings. This assistance to the imagination is the role of all devotional depictions of scenes. To do this effectively, it needs at least to be representational, and not, for example, abstract.

Last chance before Christmas for LMS Wall Calendars!

There's no obligation to get your Latin Mass Society 2021 Wall Calendars before Christmas, but if you want to give them away, it makes sense, doesn't it? So don't be shy: this is more or less your last chance to get them and other things from our online shop in time for them to be posted on the last working days of the LMS Office before the holiday. Our unique design allows for multiple beautiful photographs for every month.

Child seats in cars and the disincentive to have children

There has been a bit of chatter recently about the idea of ‘car seats as contraception’: the direct and indirect cost of children’s car seats, which were unheard of in my own childhood (was it really so long ago?) and are now required for older and older children, and take up so much space that parents of a growing family quickly have to transition to a huge car or indeed a minibus. A couple of researchers have actually done a study of the effect this has had in the USA. From the abstract:

We estimate that these laws prevented only 57 car crash fatalities of children nationwide in 2017. Simultaneously, they led to a permanent reduction of approximately 8,000 births in the same year, and 145,000 fewer births since 1980, with 90% of this decline being since 2000.

That’s a pretty vivid result, but it is just one factor in the economic disincentives to have children today. It is difficult to find larger homes: many big old houses are divided into flats. Air travel is ruinously expensive with a large family. No preference for married men with children to support is allowed in hiring or promotion, as it was in the past. And so on.

Gaudete Sunday in Holy Trinity Hethe

Last Sunday Fr Tim Finigan very kindly came to the Church of Holy Trinity, in the village of Hethe outside Oxford, to celebrate the Mass of Gaudete Sunday. I am very pleased that despite the Coronavirus this went ahead: it is one of a quarterly series of Masses in this important historic church, and we have not been able to have the last two of them.

Gaudete Sunday in Holy Trinity Hethe

Last Sunday Fr Tim Finigan very kindly came to the Church of Holy Trinity, in the village of Hethe outside Oxford, to celebrate the Mass of Gaudete Sunday. I am very pleased that despite the Coronavirus this went ahead: it is one of a quarterly series of Masses in this important historic church, and we have not been able to have the last two of them.

Gaudete Sunday in Holy Trinity Hethe

Last Sunday Fr Tim Finigan very kindly came to the Church of Holy Trinity, in the village of Hethe outside Oxford, to celebrate the Mass of Gaudete Sunday. I am very pleased that despite the Coronavirus this went ahead: it is one of a quarterly series of Masses in this important historic church, and we have not been able to have the last two of them.

Gaudete Sunday in Holy Trinity Hethe

Last Sunday Fr Tim Finigan very kindly came to the Church of Holy Trinity, in the village of Hethe outside Oxford, to celebrate the Mass of Gaudete Sunday. I am very pleased that despite the Coronavirus this went ahead: it is one of a quarterly series of Masses in this important historic church, and we have not been able to have the last two of them.