Chairman's Blog

Is Patrarchy a punishment for sin?

|

| Chaucer's Wife of Bath. What is it all women desire? |

In my last post I considered the claim that all the many Scriptural texts saying that wives should be subordinate to their husbands should be read in light of Ephesians 5:21's reference to the 'mutual submission' of Christians. Here I want to address another argument, based on Genesis 3:16, or rather the second half of it. It is part of the curse of God on Eve after the Fall (King James Version):

your desire shall be to your husband, and he shall rule over you.

The curse implies that the harmonious relationship between husband and wife, which was Adam and Eve's in Eden, will be disrupted by sin.

Pope St John Paul II suggests, or perhaps 'hints' would be a better word, that the ruling of the husband over the wife which this verse speaks of, can be seen as a part of the consequences of the Fall which can be seen as reversed in the Christian dispensation. Mulieres dignitatem 11:

Mary means, in a sense, a going beyond the limit spoken of in the Book of Genesis (3: 16) and a return to that "beginning" in which one finds the "woman" as she was intended to be in creation, and therefore in the eternal mind of God: in the bosom of the Most Holy Trinity. Mary is "the new beginning" of the dignity and vocation of women, of each and every woman.

The suggestion, if that is what it is, seems to be one of a parallel with the abolition of divorce by Our Lord, by reference to the original intention of God in creation before the Fall. Another partial parallel would seem to be the Augustinian view of political authority, which has it that it is necessary because of sin. Like death, authority, then, comes into the world at the Fall; like divorce, perhaps at least this kind of authority can be abolished with the help of grace and the sacraments.

But what does the verse of Genesis actually mean? On the face of it, it is very puzzling to connect the idea of 'desire for the husband' and his rule over the wife.

One interesting thing is that the Vulgate gives a different reading, leading to the Douay translation: 'thou shalt be under thy husband's power, and he shall have dominion over thee.' This has always been used as a text supporting the authority of the husband in marriage, but it doesn't help determine whether the power was new, after the Fall, or simply newly irksome.

Looking at the long list of Bible translations given by BibleHub, although something like the KJV wording dominates, a couple translate 'desire' in a quite different way again:

You will want to control your husband, but he will dominate you.

And you will desire to control your husband, but he will rule over you.

The reason for this is an intriguing link with a later verse of Genesis, 4:7, when again God is speaking, this time to Cain. All translations (except the Vulgate / Douai) concur this time, with something like this:

If you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door and its desire is toward you, but you shall rule over it.

(The Vulgate again treats the two phrases as reiterating each other, not contrasting with each other, giving 'if ill, shall not sin forthwith be present at the door? but the lust thereof shall be under thee, and thou shalt have dominion over it.')

It is, in fact, the same Hebrew phrase (as Robert Sungenis explains in more detail). The 'desire' of the sin, and the desire of the woman, is for domination, and contrasted with that is the possibility, or probability, that this desire will be frustrated by the assertion of authority by the other party. It is not Adam's authority, any more than Cain's inclination to upright action, which is new; it is the temptation to kick against it.

Authority is a remedy for sin, but that is not all it is. St Augustine is the classic exponent of the view that the authority of the state is a remedy for sin, but he did not regard the authority of Adam over Eve as starting with the Fall. In St Thomas Aquinas the connection between Adam's patriarchal authority and political authority is brought out. Without the Fall, Adam would have ruled his extended family; without sin, that would have been a matter of guiding cooperative action and the nurturing of civic friendship, which look very much like political aims. It is true that Christ is able to roll back some of the consequences of sin, and render some of the remedies for sin mandated in the Mosaic Law unnecessary, but there is no support in the tradition for the view that God's creative intention was for some kind of non-hierarchical, anarchist commune.

That, at any rate, is clearly the view of the New Testament authors, who show zero awareness of any new dispensation in light of the Gospel to abolish the authority of husbands over wives. On the contrary, there are more explicit references to this authority in the New Testament than there are in the Old. To interpret Genesis 3:16 as implying that the authority of husbands is a temporary expedient to deal with sin until the New Covenant, like divorce or circumcision, one needs to ignore the revealed testimony of the New Covenant itself.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Mutual submission of spouses: coherent, Pauline, true?

Among other issues raised by Pope Francis' Exhortation Amoris laetitia is the question of family life and the complementarity of the sexes. As I have pointed out on this blog, Pope Francis seems to have a relatively robust notion of the specialisation of gender roles, a subject Pope St John Paul II was less willing to broach. I have noted on this blog the strange position of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which brings up complementarity when discussing homosexual relationships. These lack 'genuine complementarity', the Catechism tells us, and therefore lack something essential to marriage. Something so essential, in fact, that its own discussion of marriage doesn't even mention it. D'oh.

Pope Francis nevertheless pays lip-service to feminism, and says that 'patriarchy', whatever he means by that, is wrong. More substantially, in section 154 he repeats in summary form the argument made by Pope St John Paul II in his 1988 Apostolic Letter Mulieres dignitatem 24, that St Paul in Ephesians wants each spouse to submit to the other (Pope Francis refers in fact to a 'Catechesis' John Paul II gave in 1982, but the argument is the same). This is something, on the face of it, which is problematic in Amoris laetitia, not because it contradicts Pope St John Paul II, but because it agrees with him.

Pope St John Paul II says very little about what 'mutual submission' actually means. There may be a 'pious reading' which would allow us to say that it says nothing in tension with previous treatments, but I want to explore the theory as standardly elaborated and understood by neo-conservative Catholic writers, of whom there are a great many. The problems with their notion of 'mutual submission' can be divided into three categories. Does it make sense? Is it the teaching of St Paul? And, Is it the teaching of the Church?

Mutual submission is a theological riposte to traditional views of male headship of the family. There are good, bad, and indifferent versions of such views, but what they have in common is that according to them the husband has some form of authority over the wife, which the wife does not have over him. There is an asymmetry in the relationship, and the family has a hierarchical structure. Instead of clarifying the nature, the limits, the purpose, or the motivation of this authority, or investigating the corresponding expectations and rights of the wife vis a vis the husband, the 'mutual submission' approach to this question is to deny the asymmetry. The most natural way to do this would be simply to say that there is no submission of the wife to the husband: there is no relationship of power or authority, and no hierarchy, within marriage. This would be the view, I suppose, of most secular people. Instead, the 'mutual submission' suggestion is that there is a relationship of power or authority, but that it goes both ways. The wife submits to the husband, and the husband submits to the wife.

At any rate, this is the language which is used, on the basis of Ephesians 1:21, where St Paul writes 'And be subject to one another in the fear of Christ', which is used by the partisans of this view as an interpretive key to understand the numerous passages in the New Testament which urge wives to submit to their husbands. Yes!, people say, wives should submit to their husbands, but look at Eph 1:21: husbands should submit to their wives too!

It may be objected, however, that the attempt to establish a position on authority within the family which is different from the secular view that there is no authority in the family, at any rate between husband and wife, fails, because it is impossible to give coherent substance to such a position. What does it mean to submit to the authority of a person who, in exactly the same way, is submitted to your own authority? I might have authority over you as the Secretary of a club you have joined, and you may have authority over me as a traffic warden over the driver of a car, but we can't have authority over each other of exactly the same kind. It just doesn't make sense. Or rather: the only sense which can be made is that the clashing authorities cancel each other out.

The proponents of this view might reply that it means that the two people locked in this Escher-like paradox of mutual subordination should always be ready to give way to the other's desires, as opposed to working out their differences by some form of bargaining. The two little love-birds, trapped forever in the closing pages of a sentimental novel, should, on this view, be constantly saying to each other 'no, dearest, we must do what you want!' Whenever they have divergent desires or opinions, which will be a lot of the time if they are rational, if they are to come to any decisions at all, they must do so in favour of whichever has best mastered the art of emotional manipulation: of conveying a desire without appearing to insist upon it. If that's not what the proponents of this view have in mind, then what it really comes down to is saying that the bargaining of the secular model should be tempered by charity and self-restraint, which may be an improvement upon secular practice but does not restore to it any kind of legitimate authority. If Scripture tells us that there is legitimate authority within marriage, then, on this view, Scripture is wrong.

So the next question is, does Scripture, and specifically St Paul in Ephesians, tell us that there is legitimate authority within marriage, of one spouse over the other? The answer of course is that this message is conveyed emphatically over and over again, not only in Ephesians, but in Colossians, 1 Corinthians, 1 Timothy, 1 Peter, and the Letter to Titus: I've listed the passages here. Ephesians 1:21 is the only apparent qualification to the principle that husbands have authority over wives and wives should be subordinate to husbands, and not the other way round. So what does Eph 1:21 mean?

A comment on a recent post this blog suggested that it is a general remark to the effect that some Christians be subject to other Christians, not only within marriage but in the household (children to parents and slaves to masters) and in society (everyone else to the Emperor). Given the structure of the letter, this suggestion makes sense.

An alternative view, which is somewhat closer to the exegesis of Mulieres dignitatem, and has the support of some Fathers of the Church, is that it is not legal submission which is at issue here, but the kind of submission made by Christ when he washed the disciples' feet. Christ did not give up his authority in this action, but illustrated the spirit which should animate it, a spirit of service. This service is proper to all Christians, who should seek to serve all, whether they have legal authority or not. So, far from being incompatible with authority, such service may be performed through the exercise of authority. So St Jerome tells us, of this verse:

Let bishops hear this, let priests hear, let every rank of learning get this clear: In the church, leaders are servants. Let them imitate the apostle...The difference between secular rulers and Christian leaders is that the former love to boss their subordinates whereas the latter serve them. We are that much greater if we are considered least of all.” (Migne PL 26:530A, C 653-654).

(I owe this quotation to a short book on this subject by Robert Sungenis, Does St. Paul Teach Mutual Submission of Spouses?, which can be bought here and is online here. He puts a number of handy quotations together, particularly from the Fathers.)

Both interpretations make sense, and it isn't necessary to decide between them here, since both messages are implicit and explicit in Scripture in other passages. It is clearly the teaching of St Paul that Christians should submit to legitimate authority, and it is clearly also his teaching that leaders should exercise authority in the interests of the community they are leading, and not for their own benefit alone. It is on the basis of the second reading, perhaps, that a 'pious reading' of Mulieres dignitatem could be constructed, to the effect that all St John Paul II really meant (when read in light of the tradition) is that, like all Christian rulers, husbands should use their authority in service to the community they govern. In any case, what is not the teaching of St Paul is the idea that wives in some sense have an authority over their husbands, such as rivals or cancels out the authority of the husband over the wife.

The final question is of the teaching of the Church. Naturally the Church does not have the authority to overturn Scripture, and we find the teaching of Scripure accepted very clearly, and applied to modern conditions, in the Papal Magisterium.

The locus classicus on this subject is Pope Pius XI's 1930 Encyclical Casti conubii, but Leo XIII (in his 1890 Encylcical Arcanum) wrote in the same vein on the subject, as did the darling of the liberals, Pope John XXIII, in his 1959 Encyclical Ad Petri Cathedram, which was written after Vatican II had been summoned. Bl. John XXIII wrote:

53. Within the family, the father stands in God's place. He must lead and guide the rest by his authority and the example of his good life.

54. The mother, on the other hand, should form her children firmly and graciously by the mildness of her manner and by her virtue.

55. Together the parents should carefully rear their children, God's most precious gift, to an upright and religious life.

56. Children must honour, obey, and love their parents. They must give their parents not only solace but also concrete assistance if it is needed.

This nicely illustrates the point I have made on this blog before, that the doctrine of male headship does not deprive the wife of authority: her authority over the household, rather, derives from the authority of the husband, even when, as may commonly be the case in practice, it is has more frequent practical application.

What can be said about the rejection of the authority of the husband over the wife in Mulieres dignitatem and Amoris laetitia? I have noted the direction a 'pious reading' might come from, but I do not want to say that the neo-conservative reading of Mulieres dignitatem is unreasonable in itself: it is, for example, consistent with what St John Paul II said in various sermons and speeches. What is unreasonable, for a Catholic, is the acceptance of a teaching at variance with the teaching of the whole Church. My question for the neo-cons at this point is simply this: can you explain why it is more scandalous, more disloyal to the Papacy, or in any way more theologically problematic, to question the teaching of an Apostolic Letter and an Apostolic Exhortation, one by a canonised Pope, rather than of three Encyclicals, one by a beatified Pope?

Encyclicals carry more magisterial authority, but this is far less important than the fact that Leo XIII, Pius XI and Bl. John XXIII are reiterating the constant teaching of the Church, the consensus of the Fathers, and the teaching of Scripture, this last both according to its most obvious meaning (a meaning to which feminists ferociously object), and its meaning according to the interpretation given by the tradition of the Church.

The stability of the Ordinary Magisterium on this can be illustrated from the liturgy, itself a 'theological source'. The traditional Nuptial Mass has as its Epistle Ephesians, 5:22-33, missing out 5:21 on 'mutual submission'. Why does it do that? Well, 5:21 has traditionally been seen as the conclusion of the previous section of the letter, a point Robert Sungenis illustrates by reference to St John Chrysostom's Homilies, so it is logical to start the lection with v.22. Accordingly, and without any qualification in terms of 'mutual submission', the lection sets out the teaching of headship as a matter of authority of husband over wife being complemented, not with more authority of the wife over the husband, but by the husband's obligation of love and self-sacrifice to his wife. It begins:

Let women be subject to their husbands, as to the Lord: Because the husband is the head of the wife, as Christ is the head of the church. He is the saviour of his body.

Tomorrow I'm going to address another aspect of the neo-conservative reading of Scripture, Genesis 3:16.

I have addressed the question of whether Patriarchy, as understood in Catholic teaching, is oppressive, here.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

That Beattie petition

Prof Tina Beattie and some rather obscure others have called on the Polish Bishops to rethink their support for a blanket ban on abortion in Poland.

Prof Tina Beattie and some rather obscure others have called on the Polish Bishops to rethink their support for a blanket ban on abortion in Poland.

It raises the question of whether a blanket ban on abortion really is the goal of Catholic political advocacy. After all, it is not necessarily wise to seek the sanction of the civil law against all immoral actions: St Augustine famously argued for the toleration of prostitution.

However, in this case, while the question of when and in exactly what form it should be proposed practically to ban abortion, there is no real question that the civil law should fail to protect the innocent. If the law does not protect the lives of children, then what is it for?

I have written something at greater length on this on my Philosophy blog; here is an 'executive summary'.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

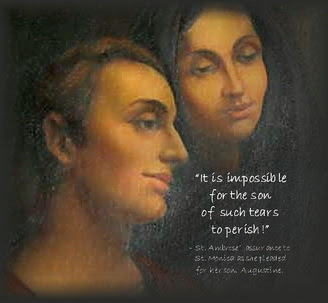

Pray for your lapsed family members

A few years ago the LMS set up the Sodality of St Augustine, whose members pray for each other's lapsed friends and relations.

A few years ago the LMS set up the Sodality of St Augustine, whose members pray for each other's lapsed friends and relations.

A member of the Sodality is initiating a monthly public rosary before the Blessed Sacrament in St Bede's, Clapham Park. I hope this might inspire others to do the same.

The dates for this Rosary: Thursday May 5th - (Ascension Day); Thursday June 2nd; July 14th. It will start at 11:30am. There is usually an EF Low Mass at 12:15pm in the Lady Chapel.

To join the Sodality, all you have to do is email the LMS to add your name: info@lms.org.uk

There is no membership fee. Members undertake to say the Sodality prayer each day - see below.

From the website:

The purpose of the Sodality is to unite the prayers of members for the conversion of those dear to them. There can be few Catholics today who do not have family members or close friends who have either lapsed from the practice of the Faith, or never had it; it is a particular source of grief when parents see children and grandchildren living without the support of the Sacraments. We take heart from the example of St Augustine, converted at last by the prayers and tears of his mother St Monica, and wish to demonstrate our fellowship with others in the same position, by praying not only for our own dear ones, but for those of others who will do the same for ours.

The Sodality takes advantage of three principles of Catholic prayer:

1. The Public Prayer of the Church is more pleasing to God than private prayer.

Not only are the Sodality's prayers supported by regular Masses, but the Sodality's own prayer is a Collect of the Roman Missal, linking our individual prayers further to the Church's prayer and the Masses being said for the same intention.

2. The united prayer of a group of Catholics is more pleasing to God than the prayers of individuals alone.

The prayers of Sodality members are united for a single intention: the conversion or return of our friends and family to the Faith.

3. Prayers motivated by charity are more pleasing to God than prayers motivated by necessity.

By praying for each others' friends, members of the Sodality show fraternal solidarity and charity, even towards those unknown to them.

The Sodality prayer (Collect of the 'commemoration' pro devotis amicis):

O God, who, by the grace of the Holy Ghost, hast poured the gifts of charity into the hearts of thy faithful, grant to thy servants and handmaids, for whom we entreat thy mercy, health of mind and body; that they may love thee with all their strength and, by perfect love, may do what is pleasing to thee. Through our Lord Jesus Christ thy Son, who liveth and reigneth in the unity of the same Holy Ghost, God, world without end. Amen.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Conference 14th May: reminder

LMS One-Day Conference - Saturday, 14 May 2016

| Edmund Adamus | Fr Serafino Lanzetta FI |

John Smeaton | Prior Cassian Folsom of Norcia |

Dr Joseph Shaw |

This is the third bi-ennial One-Day Conference organised by the Latin Mass Society, the theme of which is 'The Family'.VENUE: Regent Hall, 275 Oxford Street, London W1C 2DJ [map]

Mr John Smeaton, Director of The Society for the Protection of Unborn Children and Vice-President of International Right to Life Federation.

Prior Cassian Folsom O.S.B., founding Prior of The Benedictine Monks of Norcia.

Dr Joseph Shaw, Chairman of the Latin Mass Society, a Research Fellow at St Benet's Hall (a Permanent Private Hall of Oxford University) and St Benet's Dean of Degrees. PRE-CONFERENCE MASS PROGRAMME LUNCH COST AND BOOKING INFORMATION POST-CONFERENCE DINNER |

||||

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Is UKIP harbouring anti-Catholics?

UKIP in Scotland has been accused, by Dr Jonathan Stanley, a former party official, of trying to hoover up sectarian votes by indulging in anti-Catholic rhetoric, The Scottish Catholic Observer & The Tablet report. They refer to tweets by Caroline Santos, a candidate for the Holyrood elections which take place in May, for the South of Scotland.

I thought I'd have a look myself. Ms Santos has not deleted her tweets, which is interesting in itself, and I can't say I like the look what she says. I should add, of course, that UKIP is not the only party with activists, and even candidates for elected office, with dubious views. I'm interested in this because the target is the Catholic Faith.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

God bless Michael Voris

I've had my differences with Michael Voris (and here), but never doubted his zeal and sincerity. The idea that the repented sins of his past life should cause one to question either zeal or sincerity is patently ludicrous, from a Catholic standpoint, and like pretty well everyone in the Catholic online community I am very impressed by his response, which can be seen here.

I've had my differences with Michael Voris (and here), but never doubted his zeal and sincerity. The idea that the repented sins of his past life should cause one to question either zeal or sincerity is patently ludicrous, from a Catholic standpoint, and like pretty well everyone in the Catholic online community I am very impressed by his response, which can be seen here.

Liberals have a very different line, as their attacks on Kim Davis indicated not long ago. For anyone who has forgotten, Kim Davis was the elected County Clerk in Kentucky who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. She is a 'born again' Christian, and liberals thought they could undermine her witness to her faith by pointing at her former life - she'd been married four times. On so many levels, So what? What difference does it make to the truth or falsity of what she says? What difference does it make to the sincerity of her faith? What difference does it even make to whether she is assessed as a good person?

Liberals have a particular thing about those with same-sex attraction: that they are necessarily insincere if they don't follow the accepted homosexual political agenda. This attempt to coerce people into supporting you by denying their free will is simply insane.

The liberal media message about politicians and other opinion-formers seems to be that they are not allowed to talk about morality, or even about family policy, unless they are saints, because they would be hypocrites. And not if they are saints either, because that means they are out of touch. This neat little pincer movement means that no-one is allowed to talk about morality at all, and no one is allowed to say, for example, that two-parent families, with one parent of each biological sex, are preferable, other things being equal. This is not about hypocrisy, it is just about silencing inconvenient voices in public debate.

That's what they wanted to do with Kim Davis, and I have no doubt that this is what lots of people would like to do to Michael Voris. Voris is in a different position, however, since his audience is made up of Catholics serious about their Faith, and part of being serious about Catholicism is understanding the reality of repentance. We may not make as much fuss about reformed sinners as some evangelicals do, but we understand the reality of the phenomenon, and that the difference between St Augustine and the average pewsitter is just one of degree. Serious Catholics have not the slightest problem with listening to the insights of John Pridmore, a former gangster, or Joseph Pearce, a former senior National Front activist. The liberals can't harm Michael Voris by their threatened revelations; his pre-emptive confession of more details about his past life - the sinfulness of which he has never hidden - is not only the right thing to do in terms of crisis-management, is not going to do his reputation any harm: quite the opposite.

While rejoicing, with the angels, over the repentance of each sinner, I wouldn't want Catholics to adopt a more evangelical attitude, which could turn into a kind of voyeurism of sin. Voris' recent testimony is a model of honesty and also of prudent restraint about details. Let's not let our emotions run away with us about these things, and seek bigger and bigger thrills about people's conversion stories.

There are two reasons why the Catholic attitude is, or should be, different from the Evangelical one. First, we do not see conversion as necessarily either instantaneous or permanent. Conversion is a daily necessity, and involves the slow and painful overcoming of bad habits by good ones. Grace can be genuinely accepted and then lost. No one knows if he is saved until the moment of death and judgement, unless God grants him a private revelation, and that is rare.

A moment of conversion can be spectacular, when a sinner accepts the grace of repentance and makes a perfect act of contrition, and / or receives sacramental absolution: then he is freed from mortal sin, restored to spiritual life, and things may look suddenly different after a long period of darkness. But not all conversions are like that, and even when they are, hard work remains, and success is not guaranteed.

The second reason is that we don't think that all saints were once sinners. A lot were. A lot weren't. The point is, it is not a necessary rite of passage, as it is sometimes treated in Protestant thinking. Sentimental hagiographies from the late 19th century sometimes play down the sins of the saints to a ridiculous degree, but let's not make the opposite mistake, and run away with the idea that to be an authentic Christian you have to sleep around when young, and maybe kill someone in a pub brawl. Our Lord is our model, and He never committed even a venial sin. Our Blessed Lady was not a sinner: not even for a moment. St John the Baptism was freed from the stain of Original Sin in his mother's womb, so he never experienced the sinful desires of the fallen human condition. St Therese probably never committed a mortal sin. Avoiding sin does not make you inhuman: it makes you more human, human as God wants us to be.

Sin is a tragedy. God's grace and forgiveness is a miraculous triumph over that tragedy. The wonderful variety of saints in heaven illustrates the infinite creativity of God's providence.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Why the 'Old Mass' disturbs a conformist age: in the Catholic Herald

That liturgical traditionalism should lead away from, and not towards, an uncritical acceptance of the established order of politics and society should not be surprising, and this reality is manifesting itself again today. Attending the ancient liturgy now, as in the past, implies taking seriously the longer view: a view from which divorce and abortion are not just facts of life, where the vision of Catholic education is not just a matter of tweaking the National Curriculum, and where the Church’s teachings about Usury and the Social Kingship of Christ might be worth a second glance. In terms of the party politics of 2016, it is a view, as Pope Francis would express it, from the periphery. It is view which takes the vulnerable, the ignored, and the exploited, more seriously than it takes the cognoscenti.

This is matched by the Traditional Mass’s ability to attract diverse congregations. At a time when too often Catholics segregate themselves into social, educational, and linguistic categories by choosing which parish and which version of the Ordinary Form they attend, a complete range of people can be found at the EF. Catholics attracted to a more counter-cultural view of the Faith, naturally see the Faith which unites them as more important than anything which divides them.

Ascension and Bach: another lost opportunity

|

| J.S. Bach |

Another meeting of the Bishops' Conference of England and Wales, and another missed opportunity to restore Ascension, along with Epiphany and Corpus Christi, to the days they have occupied for umpteen centuries, the days they are celebrated in St Peter's in Rome, and the days they are celebrated even by many non-Catholic Christians. And to the days they are celebrated in the Extroardinary Form of the Roman Rite.

On Sunday 8th May, Oxford Bach Soloists are doing something rather fun: they are singing the two Cantatas written by J.S. Bach for the Sunday after Ascension. Bach wrote masses of cantatas for liturgical use, and they correspond to the liturgical calendar, with references to the readings and proper prayers. He did this for the German Lutherans, and the German Lutherans had essentially the same calendar, the same readings, and even many of the same prayers, as the ancient Latin Missal. The same is true of the Book of Common Prayer, where, with the odd theological tweak, you'll see Cranmer's translations of ancient Latin collects on the very same days as they are used in the Extraordinary Form.

So Bach wrote these particular cantatas for 'Exaudi Sunday': the Sunday 'within the Octave of the Ascension' (in the days Ascension had an octave), whose Introit, the first prayer of the Mass, starts with the words 'Exaudi, Domine, vocem meam': 'Hear, O Lord, my voice!' The Epistle, from 1 Peter 4, is an exhortation to persevere in good works. The Gospel, from John 15, is about how the Holy Ghost at Pentecost will give testimony, with the warning that the Apostles will be ejected from the Synagogues, and those killing them will believe that they are doing a good work before God.

The collection of these texts in one liturgical celebration is, like so much of what inspired Bach, Catholic, for all the theological differences between Lutherans and Catholics in his day. In important ways it is Catholic liturgical spirituality and thinking which form the backdrop to some of his finest work. But these liturgical artefacts are no longer available as a coherent whole to Catholics attending the Ordinary Form. In those vanishingly rare places where Introits are sung in the Ordinary Form, 'Exaudi Domine' is given for the 11th Sunday of Ordinary Time, whose relationship with Easter depends on how early or late Easter is. The lections have been exiled from the Sunday cycles altogether.

But in England and Wales, the very concept of the Sunday after Ascension has now been abolished. We are in the embarassing situation of saying to people like the Bach soloists: well, these texts used to be used in Catholic worship; the idea of a Sunday to pause for reflection between the Ascension and Pentecost used to be one we had in the Catholic liturgy; we used to have some continuity with this historical, cultural, and spiritual reality Bach is writing this wonderful music about.

The idea of using these kinds of cultural hooks to engage in some form of subtle evangelisation is associated with Pope Benedict, but it was Pope Francis, in Amoris laetitia, who wrote (208):

Nor should we underestimate the pastoral value of traditional religious practices. To give just one example: I think of Saint Valentine’s Day; in some countries, commercial interests are quicker to see the potential of this celebration than are we in the Church.

As good as his word, every year, on St Valentine's Day, Pope Francis gives a blessing in St Peter's Square for young couples. But wait! When is St Valentine's Day? It does not exist in the 1970 Calendar.

As I have noted on this blog before, Bugnini consciously worked against traditional religious practices, which had found their way into popular culture, because he thought of them as a distraction from the liturgy. In the 1956 reform of Holy Week many traditional practices became impossible, and others were left stranded in the wrong place: an example being the blessing of eggs in Poland, which still happens on the afternoon of the Saturday of Holy Week, even though this is now before the Vigil, and not after it.

The process of the liturgy seeping into culture, creating cultural opportunities for evangelisation, is the work of centuries. Destroying these connections is the work of moments.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Amoris laetitia on gender roles and parenting

|

| Don't be too indulgent to them, says Pope Francis. Children at the Family Retreat. |

Tim Stanley has written an article in the Telegraph about how Pope Francis has turned out, in Amoris laetitia, to be something of a social conservative, highlighting a passage I drew attention to on this blog about the handing on of traditions, and the need for continuity and a sense of history. I'd like to take this idea further, on the specific issue of the kind of family the Holy Father wants to foster.

Pope Francis says he is in favour of Feminism and against Patriarchy, but liberal readers may beg to differ, having rather different ideas about what those terms mean. Pope Francis writes:

54. There are those who believe that many of today’s problems have arisen because of feminine emancipation. This argument, however, is not valid, “it is false, untrue, a form of male chauvinism”. The equal dignity of men and women makes us rejoice to see old forms of discrimination disappear, and within families there is a growing reciprocity.

The key word here is 'recoprocity': equal dignity does not, for Pope Francis, mean 'interchangable in function', it means equal in dignity, with distinct functions. And so he goes on - yes, I'm afraid so - to affirm traditional gender roles and traditional parenting.

You see, men and women just aren't the same:

136. Men and women, young people and adults, communicate differently. They speak different languages and they act in different ways.

Nor should they be the same.

173: I certainly value feminism, but one that does not demand uniformity or negate motherhood. For the grandeur of women includes all the rights derived from their inalienable human dignity but also from their feminine genius, which is essential to society. Their specifically feminine abilities – motherhood in particular – also grant duties, because womanhood also entails a specific mission in this world, a mission that society needs to protect and preserve for the good of all.

He has encouragement for 'stay-at-home' mothers.

49. The problems faced by poor households are often all the more trying. For example, if a single mother has to raise a child by herself and needs to leave the child alone at home while she goes to work, the child can grow up exposed to all kind of risks and obstacles to personal growth.

He also speaks of the essential role of fathers.

55. Men “play an equally decisive role in family life, particularly with regard to the protection and support of their wives and children… Many men are conscious of the importance of their role in the family and live their masculinity accordingly. The absence of a father gravely affects family life and the upbringing of children and their integration into society. This absence, which may be physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual, deprives children of a suitable father figure”.

Taking up one's gender role is actually a central part of spiritual growth in marriage.

221. Might we say that the greatest mission of two people in love is to help one another become, respectively, more a man and more a woman?

A traditional form of upbringing for children includes, naturally, discipline. Pope Francis devotes a whole sub-chapter to the 'The value of correction as an incentive'; it begins:

268. It is also essential to help children and adolescents to realize that misbehaviour has consequences. They need to be encouraged to put themselves in other people’s shoes and to acknowledge the hurt they have caused. Some punishments – those for aggressive, antisocial conduct - can partially serve this purpose.

Pope Francis does not want parents to be easy-going. On the contrary:

260: Parents need to consider what they want their children to be exposed to, and this necessarily means being concerned about who is providing their entertainment, who is entering their rooms through television and electronic devices, and with whom they are spending their free time. ...Vigilance is always necessary and neglect is never beneficial.

They should imbue their children with the virtue of modesty:

282. A sexual education that fosters a healthy sense of modesty has immense value, however much some people nowadays consider modesty a relic of a bygone era. Modesty is a natural means whereby we defend our personal privacy and prevent ourselves from being turned into objects to be used. Without a sense of modesty, affection and sexuality can be reduced to an obsession with genitality and unhealthy behaviours that distort our capacity for love, and with forms of sexual violence that lead to inhuman treatment or cause hurt to others.

Pope Francis goes on in the following sections to say that sex education should precisely not be what it is in progressive educational theory: an education in 'safe sex.'

He is equally emphatic about the role of parents as primary educators, and develops this point at some length. Parents should set out to form their children morally:

264. Parents are also responsible for shaping the will of their children, fostering good habits and a natural inclination to goodness. This entails presenting certain ways of thinking and acting as desirable and worthwhile, as part of a gradual process of growth.

This should include - indeed, start with - table manners.

266. Good habits need to be developed. Even childhood habits can help to translate important interiorized values into sound and steady ways of acting. A person may be sociable and open to others, but if over a long period of time he has not been trained by his elders to say “Please”, “Thank you”, and “Sorry”, his good interior disposition will not easily come to the fore.

All of this guidance and formation is to make possible a child's freedom, which is not conceived in a liberal fashion, which is to say in a negative fashion, as the ability to go in lots of different directions, but positively, as having as few impediments as possible in grasping the true and good.

267. Freedom is something magnificent, yet it can also be dissipated and lost. Moral education has to do with cultivating freedom through ideas, incentives, practical applications, stimuli, rewards, examples, models, symbols, reflections, encouragement, dialogue and a constant rethinking of our way of doing things; all these can help develop those stable interior principles that lead us spontaneously to do good.

A picture of the Bergoglian household emerges, which looks like something, I suppose, which would have been recognisable to Pope Francis' own childhood: he was born in 1936. A person of that generation, aware of the changes in attitudes which have taken place since then, has to make an assessment and decide what to reject and what to uphold of the way things used to be done. Pope Francis warns us against inflexibility, against legalism, and against coldness, but he wants to hand on to the future what was good about the traditional forms. He warns fiercly against the selfishness which often leads to divorce, against contraception (80), against abortion (83), against IVF (81), against gender theory (56), and against same-sex marriage (250: the only mention of homosexuality in the document).

In dealing with the aftermath of divorce, he may not speak as clearly as we would like, and he may not even be on the right track in stressing inclusiveness over the problems of bad example and infidelity. He does at least make it clear that these are matters of policy, and while passionately adhering to his own view, there is no question of doctrinal teaching at issue. On the contrary, things are left to bishops and priests - a burden which they may not always welcome. Nevertheless, the overall picture gives scant comfort to liberal Catholics, and absolutely none to liberals outside the Church.

I was struck, discussing Amoris laetitia on national television, how utterly irrelevant to the concerns of even Catholic progressives the apparent concessions made to them in the Exhortation are. There was a man from ACTA, who complained that the views gathered in the pre-Synod questionnaires had been ignored, and a lady from Women's Ordination Worldwide who wasn't going to be happy until the Pope was a woman. The presenter, Nicky Campbell, wanted to bring the conversation around to contraception, and a former News of the World editor wanted to rail about the Church's role in stopping the spread of abortion to Northern Ireland. This may be an argument that those apparent concessions were pointless. But it also shows that they aren't going to make as much difference as some people imagine.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.