Chairman's Blog

Fr Longenecker, the Latin Mass, and the magic bullet

Reposted from October 2015.

|

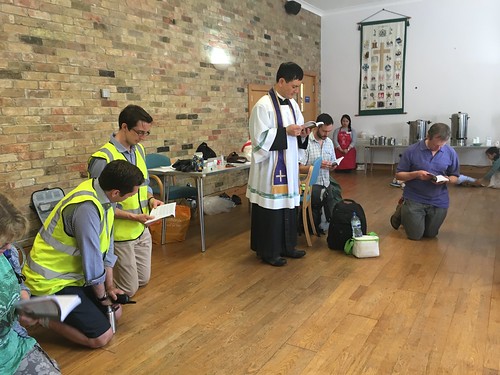

| An act of revence during Mass before the Blessed Sacrament Exposed, for Corpus Christi: it tells us something, does it not? (What does the little chap on the left think?) |

Further to my post the other day someone noted a recent post on this topic by Fr Dwight Longenecker: 'Is the Latin Mass a Magic Bullet?'. In it he attempts to put the thoughts of those 'conservative' Catholics who don't much like the Traditional Mass, about the relationship between the crisis in the Church and the liturgy, into order. The result is fascinating. Some key quotes, with a few comments of mine in black.

The problems in the Catholic church are not due to lack of reverence at Mass. The lack of reverence at Mass is due to the problems in the church. But it can't help, can it?

Simply obeying the rubrics or performing the Mass in this direction or that direction or standing here or there or wearing this particular vestment or that particular vestment or holding your fingers together there and bowing properly there do not necessarily make a Mass reverent. It makes the Mass more formal. .... So what's the point of them?

Here is my main point: I think those who blame all the problems of the church on the Novus Ordo are simply missing the point. If there are things wrong with the Novus Ordo they are symptoms, not causes. The core problem in the church is not the Novus Ordo or the liturgical abuses or the bad hymns and liturgical dance and all that awful stuff. So why exactly are these things 'awful'?

The reason the Novus Ordo so often seems irreverent is not any intrinsic deficit in the Novus Ordo. (otherwise why would Holy Church say that it remains the Ordinary Form of the Mass?) Instead the Novus Ordo is sometimes celebrated irreverently because people regard the Mass as a celebration of their social activism, or a community festival to increase their self esteem or a sentimental, individualistic, spiritual comfort session. They have ceased to really believe in sin and grace and a God who saves, and instead they look to one another for their salvation. So there’s not much reverence required there. Aren't these beliefs reinforced by the abuses which express them?

The phrase 'lex orandi lex credendi' clearly doens't resonate with Fr Longenecker. Whether he realises it or not, he goes far further than simply dismissing the straw man claim he started with ('Some traditionalists also seem to think that all the church’s problems would be solved if only we would all return to the Latin Mass everywhere and at all times.': dude, I don't believe you have friends as stupid as that). His position appears to be the opposite extreme: that liturgy has no impact at all on the spiritual lives and religious attitudes and beliefs of the Faithful.

This is a claim of such utter insanity that I can't imagine Fr Longenecker consciously espouses it. But if he simply thought: 'Of the influences on Catholics, catechesis is on balance more important than the liturgy', then his conclusions would not follow. If the liturgy has some influence, then it would be at least part of the explanation for the strange phenomenon of well-catechised Catholics clustering around one Form of the Mass; at least part of the cause of the problems in the Church; and so on. He would, in short, find himself expressing a position we could all agree with.

The influence of the liturgy on the spiritual lives and on the dogmatic beliefs of Catholics is a constant theme of the Church's teaching on the liturgy. I could point to a score of references in the Magisterium, and it a major theme in Cardinal Ratzinger's writings. That a priest should be betrayed into suggesting, even inadvertently, that the liturgy makes no difference to what people end up believing is itself a symptom of a deep malaise in the Church.

|

| A reverent form of receiving Communion, which expresses the belief we have about it: or just an empty formality? |

I would hope that all minimally sane Catholics would immediately agree that a range of things influence our spiritual lives and beliefs. Catechesis is one, but there are many others: our experience of religious art; cultural references of all kinds; newspapers, blogs, and books, including spiritual reading and study; the example of others; conversations; our own spiritual endeavours and experiences; and of course the liturgy. Looking at a community, or indeed the world-wide Church, we will expect to find these influences interacting, reinforcing or counteracting each other as time goes on. A big push by one or a group of them can draw the others in their wake: conversations take off from what we've read, the liturgy can be influenced by conversations, catechesis can be influenced by the liturgy (think of all those theologically weird hymns), catechesis stimulates spiritual writing or Catholic journalism or blogging, and round it goes again.

What Cardinal Ratzinger, and for that matter Pope Pius XII in Mediator Dei, and Vatican II, and the whole Magisterium, is telling us is that the liturgy is not just a small part of this process: it can't be dismissed as an epiphenomenon, a 'sympton not a cause': no, it is of central importance. It's not the only thing - that idea is just silly - but it is, to coin a phrase, the source as well as the summit of the Christian life. (Many readers will know I'm paraphrasing not some loony trad, but Vatican II.)

Fr Longenecker should reflect on the fact that while all practising Catholics hear (if not actually listen to) sermons, adult Catholics are completely immune to systematic catechesis, except for temporary and atypical situations like marriage preparation. Your exciting new catechetical tools are not going to reach adults; the ones still practising, however, are going to be influenced by the liturgy. Even people who think that liturgy is a less powerful tool than catechesis in conveying theological ideas and habits of prayer, should still recognise its supreme value for those not in any kind of catechetical program, which is almost all adult Catholics.

I find it deeply disturbing that Fr Longenecker and others like him should be so deaf to Vatican II and the rest of the Magisterium on the importance of the liturgy. We seem to have bred up a generation of 'conservative' Catholics who are simply non-liturgical in their thinking. It doesn't make sense, of course, to say that you are in favour of things like Latin and worship ad orientem if you think they make no contribution to the reverence, the worthiness, of the liturgy. The contrast he offers between reverence and formality is, well, amazing, and I'm sorry he didn't have the time to explain what he means. He appears to think that the rubrics of the Mass have no meaning and convey nothing to the onlooker. The outlook all this suggests is mind-boggling.

But Fr Longenecker is in favour of Latin and ad orientem worship and welcomes the spread of the Traditional Mass, so looking at this incoherent position from the other end, it would follow that he cannot believe that it makes no difference, has no positive effect on the faithful, is not a more reverent act of worship to offer God, and so on. So I suppose we just have to leave Fr L suspended between the two positions, like a novice trapeze artist.

The rest of us, however, can hold fast to the fact that the Mass is the central mystery of our spiritual lives. The offering of the Unbloody Sacrifice with beauty and reverence, and in continuity with our predecessors in the Faith, is of fundamental importance in itself, and of fundamental importance for us. We know from experience what we are taught by the Church in the magisterium, that the liturgy is a 'school of prayer', that it is capable of softening the hardened heart, of consoling us and giving us strength to live our Christian lives. It puts us in direct touch with God in a way that nothing else can: not even the personal religious experiences of the great mystics can compare with the experience of Christ, really and objectively present upon the Altar and offered to the Father as a sacrifice for the sins of the world.

Experiencing this mystery, being able to grasp deep down that this is what is going on, is not guaranteed by the sacramental validity of the rite. I can feel the anger of the neo-cons rising as I write these words: how dare I say that the supernatural mystery of the Mass is less visible, is harder to experience, in a vernacular celebration larded with abuses? Sorry, guys, it is a fact we have all experienced; don't take it out on me, take it out on the Congregation for Divine Worship:

... abuses “contribute to the obscuring of the Catholic faith and doctrine concerning this wonderful sacrament”. Thus, they also hinder the faithful from “re-living in a certain way the experience of the two disciples of Emmaus: ‘and their eyes were opened, and they recognized him.’”

Or better still, take it out on St John Paul II:

In various parts of the Church abuses have occurred, leading to confusion with regard to sound faith and Catholic doctrine concerning this wonderful sacrament.

If the mystery is not vividly conveyed to you in Mass, perhaps you should try coming to the Traditional Mass.

A critique of a related opinion of the late Cardinal Hume on reverence and Latin can be found here.

Photographs from SS Gregory & Augustine; more on this Mass here.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Mass in Snave, the Kentish 'Marsh church', this Saturday

This Saturday - A Missa Cantata in the marshes. (Click for a map.)

For only the second time since the reformation, St Augustine's in Snave, a medieval Kent church will hold a Latin Mass this Saturday 24th September at 12 noon.

This is an extremely important event because last year was the first time since the Reformation that Mass was celebrated in the church.

Snave is one a group of medieval churches built to serve very small communities on Romney Marsh in Kent. Now redundant, they are in the care of the Romney Marsh Historic Churches Trust

The celebrant will be Fr Marcus Holden (Rector of the Shrine of St Augustine, Ramsgate) and music will be supplied by The Victoria Consort.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Communist infiltration: a comforting fantasy

Today I'm re-posting this from January 2014, in response to comments on the book I discuss, Marie Carré's AA-1025, by David Martin over on 1Peter5.

This post of generated a bit of comment when first published, partly from people apparently incapable of understanding the genre of Carré's book. It is a work of fiction; that is not, in itself, a criticism of it, just a classification. It is an exploration of an idea, suggested by the testimony of Bela Dodd and other (alleged) Communist infiltrators into the Catholic Church. What exactly were they doing? What historical events or trends can be attributed to them? So, the reader must ask: does this exploration yield convincing results?

The answer is that the book is very clearly a product of its time, the early 1970s. Vatican II and the liturgical reform were, understandably, uppermost in the author's mind. I point out in the post that the author completely missed the sex abuse scandal, in which real Communists were very interested indeed in the Soviet bloc at the time she was writing, though this was not then publicly known; she also misses Liberation Theology, which was in advanced stages of preparation at that time. Instead she latches onto the liturgical reform, which was something for which real Communists showed no enthusiasm whatsoever. Maybe they believed the claim, frequently made at the time and since, that the Novus Ordo would be a more effective tool of catechesis when preaching was heavily restricted in Communist countries. In any event, the implementation of the reform was actually delayed in parts of the Communist world, by up to 20 years. Nothing like it was ever imposed on the Russian Orthodox Church, over which the Soviet authorities had - to say the least - rather more influence than they had over the Catholic Church. In China, its implementation was a major goal of Vatican diplomacy for years, a hard-won concession from the authorities; the Novus Ordo was first celebrated (by Cardinal Zen, that Communist cat's paw - not) in mainland China in 1989. Marrie Carré wasn't to know all this, of course. But the result is that her assessment of Communist strategy in opposing the Church is way off the mark.

------------------------------------------------------------------

I've just read Marie Carré's strange book AA-1025: Memoirs of the Communist Infiltration into the Church. I've seen it around and hear references to it so I got round to reading it. It is very short, only 120 pages or so; someone has gone to the trouble of putting the whole thing online. It is not very well written, but you can find lots of breathless endorsements online so I thought I'd say something about it.

First of all, it is obviously a work of fiction. It says so on the flyleaf ('This book is a dramatized presentation of certain facts...'). The premise of the book is that it is the autobiography of a Soviet agent who had got himself ordained, which is discovered by chance when he is involved in a car accident. The idea is that Communist efforts to subvert the Church from the 1930s onwards would explain the Church's problems, particularly theological liberalism and the liturgical reform. (More detail here.)

The book was first published (in French) in 1972; since then two things have happened to demolish the plausibility of this idea. (I don't say: to demolish it as an alleged record of a conspiracy theory, because, to repeat, the book is fiction.)

The first is the way real Communists reacted to developments in the Catholic Church, particularly in light of what we now know about their activities in the Cold War from secret files which have become available since the fall of the Soviet Bloc. It is perfectly true, and under the circumstances perhaps inevitable, that in countries under Communist rule the Catholic Church (and the Orthodox too) was riddled with agents; the interesting thing is that the activity of these agents was not, as far as one can see, connected with any terribly sophisticated ideological subversion of the Church. As far as theological and liturgical liberalism is concerned, Poland (for example) under Communism was rather conservative; Communion in the Hand did not come about until after the fall of Communism (and, interestingly, the death of Pope John Paul II). In China, the Patriotic Catholic Church, a wholly-owned arm of the Communist state, was very slow in introducing liturgical reforms after the Council, and the Traditional Mass is still widely available there.

What were all the Communist agents doing? Straightforward stuff about blackmailing each other and trying to stop effective political opposition to the regime being aided by the Church. Just what you'd expect, in fact. Of course, the Communists hated and feared the Catholic Church, and wanted to advance Atheism, but they weren't as clever as all that and anyway had other fish to fry.

The second is the sex-abuse scandal. If anything might lend itself to manipulation by Communists, this would be it. Marie Carré is as blissfully unaware of this possibility as everyone else was in 1971; it doesn't come up in the book. And although sexual failings were meat and drink to the system of blackmail and character assassination carried out by the Communists against Catholic priests, there is no reason to think that any blame for the crisis in America, Ireland, Germany and the UK can be laid at their door.

Who can we blame for the crisis in the Church? Naturally there are external influences on the Church: philosophical and theological ideas from Protestantism, the Enlightenment, and Freud, for example. And in a sense all problems in the Church come from Catholics not being Catholic enough, adopting ideas incompatible with the Faith. But the origin of the ideas of 1960s liberalism is quite clearly the modernism of the early 20th century, which in turn derived from the liberalism battled by John Henry Newman in an Anglican context in the middle of the 19th century. These poisonous ideas, such as the denial of the transcendent in theology and the liturgy, and the denial of moral absolutes leading to sex abuse, were incubated in Catholic institutions from early in the 20th century, and became the badges of the superior people: the people who regarded themselves as real scholars, real intellectuals, people who weren't backward, childish, reactionaries.

An excellent guide to this process is Malachi Martin's book The Jesuits.

One thing the Carré book is correct about, is to draw our attention to the long-term causes of the problem, and stop us imagining that everything was perfect up until 1962 or thereabouts. In terms of the intellectual leadership of the Church, the revolution had already triumphed: it just needed to manifest itself. But we can't blame the Reds for this. The rot came from within.

A third priest for the Institute in New Brighton

From Canon Amaurty Montjean of the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, Rector of the Shrine of SS Peter & Paul and St Philomena in New Brighton, the Wirral, the 'Dome of Home':

See their website here.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Letter on Child Protection

I'm not going to comment on the news about Ampleforth College; but today I am reposting this from January 2012, about Downside.

------------------------------------------------

This weekend the Catholic Herald has published a letter of mine on the subject of 'Child Protection'. It responds to an article by Will Heaven.

Will Heaven (Comment, Jan 20th) tells us that monastic schools, like Downside, where there have been failures of child protection, should be handed over to lay trustees. By the same logic, I assume he would want the many lay schools plagued by such failures to be handed over to monks.

Will Heaven (Comment, Jan 20th) tells us that monastic schools, like Downside, where there have been failures of child protection, should be handed over to lay trustees. By the same logic, I assume he would want the many lay schools plagued by such failures to be handed over to monks.

We need to look, not at the clerical or lay status of trustees, but at their attitudes and policies. Unfortunately the leadership of Catholic schools appears to be following the example of its secular counterpart, both by imposing explicit sex education on our children and by an increasing reluctance to expect staff to live in accord with Church teaching.

The secular model is to promote anarchic sexual liberalism in schools, balanced by an hysterical concern for the procedures of child protection. This is not going to solve the problem of the sexual exploitation of children in the long term. Until the Catholic school sector is prepared to buck this trend decisively I, like an increasing number of Catholic parents, will be teaching my children at home.

Yours sincerely,

Joseph Shaw

Two things struck me about Heaven's article. The first was his idea that the problems at Downside would go away if the monks were no longer the trustees. It is reasonable I suppose that a religious order which makes a hash of an apostolate hands it over to someone else, but Heaven's suggestion smacks of anti-clericalism. How, exactly, would having lay control help? Hasn't he noticed all the non-religious, indeed non-Catholic schools which have had child protection issues? It is the attitudes and policies of the individuals in positions of authority which are important, not whether they wear clerical dress. On this, Jonathan West of 'Confessions of a Skeptic' agrees with me, in his Tablet article this week and his comments under Heaven's article: lay leadership is not a 'silver bullet'. (Tablet link for subscribers.)

I have another concern about the attempt to separate monastic schools from the monasteries which founded them. If this happens we will have two institutions sharing a site, but nothing else. It will be entirely reasonable for the monastic community to ask why they are allowing this alien institution to take up so much of their land, rent free. Why not turn it into luxury flats? Hybrid models, in which the Abbot appoints some trustees and some unnamed person others, seem to be a recipe for permanent conflict.

The other thing which struck me was Heaven's jaunty reference to Downside going mixed. He writes:

You might think that the sudden onset of colder weather might make Heaven wonder whether 2005 was spring after all. For why did they they let in girls, to a school which had been single-sex since its foundation a century earlier? Did the monks suddenly feel a special charism to look after the emotional needs of adolescent girls? I don't think so. Letting in girls enabled it to bring number back up to capacity: oh, that's it!

I don't blame the monks of Downside in particular, they were just following the trend. The point is that this is a trend in which the interests of pupils were sacrificed to financial considerations, and to educational fashion. No one was ignorant, by 2005, of the educational benefits to girls of being in a all-girls' school; the subject had been studied to death. Catholic boys' schools, usually with superior brand-recognition and resources, continued to undermine the girls' schools by going mixed because it was in their interests, not in the girls'.

If anyone is interested in the Church's teaching on co-education, they can look at Pius XI on the subject in 1939 (Divine illius magistri):

If anyone is interested in the Church's teaching on co-education, they can look at Pius XI on the subject in 1939 (Divine illius magistri):

This is related, by the denial of original sin, to the real elephant in the room, which I mention in my letter, which is the sexualisation of children. The motto of the secular educational establishment is 'Do whatever you are comfortable doing; don't let anyone make you feel guilty about it; don't let anyone do to you what you're not comfortable with'. This places the burden of child protection on the children themselves. Since the only standard of what is abusive is the child's perception, accusations of abuse are justified almost by definition. By the same token, the 'grooming' activities of abusers, in which they attempt to convince their victims that abuse is really ok, have been adopted as school policy: nothing is not ok, children, if you just accept it. This is why we have the extraordinary situation in which schools are deliberately sexualising children, and then crying blue murder at the least plausible accusation.

The Catholic Church has a great opportunity here, because the secular orthodoxy has become so extreme, and so incoherent, that at least some people will give an alternative a hearing. The Natural Law tells us what is abusive, and we have the intellectual resources to create an environment for children in which abuse is less likely to happen. Why not do it, and make a virtue of it?

I see Oona Stanard is stepping down from the Catholic Education Service. Perhaps her replacement can give these matters some serious consideration.

Full disclosure: I am a Fellow of St Benet's Hall, a Hall of Oxford University whose trustees are the Abbot and Council of Ampleforth Abbey.

Oxford Pilgrimage 29th October

The Latin Mass Society's Pilgrimage to Oxford - which I organise as the Society's Local Representative - will take place on 29th October, with High Mass in Oxford's Blackfriars at 11am, in the traditional Dominican Rite, followed at 2pm by a procession to one of the two sites of martyrdom in the city.

We've been doing this since 2005, but it didn't take place last year because the ceiling of the church had collapsed. I'm glad to say that it has since been repaired! It is a wonderful event, we get a good number of people to process through the streets of Oxford with a processional statue, and we have a mock-up gallows at this site of martyrdom which always draws the interest of passers' by, and the occasional comment in a student newspaper.

It is worth making the point: it wasn't only Anglicans who died for their beleifs, or religiously motivated actions, in Oxford. Four Catholic martyrs died in 1589, on this spot, two priests and two laymen, and another priest, Bl George Napier, died on the Castle gallows in 1610. All have been beatified.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

LMS Pilgrimage to Aylesford, 1st October

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

LMS Tyburn Walk 2016

In 2014 the Latin Mass Society organised a devotional 'walk' from the site of Newgate Prison to the site of the Tyburn Tree, the gallows where prisoners from Newgate were executed, among them at least 105 Catholic martyrs. We didn't manage to do it last year, but it happened on the Bank Holiday Monday this week, while I was still in Walsingham. Here are some pictures, thanks to @idlerambler.

In 2014 we had 45 people with us; this year, there were 70. Also, this year we had Low Mass in Tyburn Convent, build near the site of the Tyburn Tree, which was a great privilege.

The walk was led by Fr Mark Elliot-Smith of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, who is based nearby in Our Lady of the Assumption, Warwick Street.

The above is St Patrick's, Soho Square, which is close to the route. And below is Tyburn Convent.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Walsingham 2016: Photo essay

I took very few photos this year, since John Aron was taking lots; I've included some of his below.

In a nutshell, the LMS Walking Pilgrimage from Ely to Walsingham was a great success, with lots of people, lots of prayers and songs, and lots of graces. And lots of children.

We had with us Fr James Mawdsley FSSP, now at St Mary's, Warrington, and Fr Michael Rowe from Perth in Australia, who has been with us twice before. We were able to have High Mass with the help of Br Anthony of the Friars of Gosport, who is awaiting ordination. We also had a Fraternity seminarian, the Rev Mr Thomas O'Sullivan, very well known to me from his Oxford days; he was MC at our masses, another Gosport Friar, Br Philomeno, who has done the pilgrimage before, and a lay brother of the Society of St Vincent Ferrer, Br Vincent Hoare, who sang with our small schola.

The Blessing of Pilgrims from the Roman Ritual.

Did I mention there was also lots of walking? About 58 miles, in fact. The weather was on the hot side, but nothing too extreme.

Mgr John Armitage, Shrine Custodian at the Catholic Shrine, received a First Blessing from Fr Mawdsely, who was ordained in June.

The Shrine has been given the status of Minor Basilica since our last visit.

For our big Mass on Sunday and the Holy Mile and our devotions at the site of the Holy House, we were joined by lots of people who were there for the day, and people from Youth 2000, which takes place the same week.

Fr Rowe celebrated the Sung Mass we always have on the Monday following the pilgrimage in the Slipper Chapel.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Succesfull walking pilgrimage in Scotland

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.