Chairman's Blog

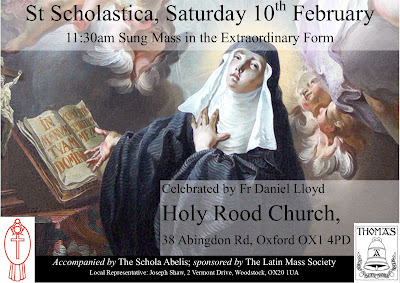

Sung Mass for St Scholastica in Holy Rood

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Thoughts on the Mortara case

As has been well described elsewhere, in 1858, in Bologna when it was part of the Papal States under Pope Pius IX, a 6-year-old Jewish boy who had been secretly baptised by a servant when he had been thought to be at the point of death, was taken from his parents to be raised a Catholic.

This was a rare kind of case, but it had been contemplated in the civil law of the Papal States, and the decision was in accordance with longstanding practice. In the face of an international outcry, Pope Pius IX refused to restore little Edgardo to his family.

First Things has been getting more ‘traddy’ in recent years but they have jumped the shark by publishing a defence of this action of Pius IX by a Dominican theologian, Romanus Cessario. This must surely be one of the most indefensible actions by any Pope of modern times, not least because there is no dispute about the facts of the case. Nothing in the article made me remotely more sympathetic to this action of Pius IX.

I have a lot of time for Pius IX, in general. I also think the Papal States were good and necessary (so necessary, in fact, that they had to be resurrected in miniature form in 1929). Furthermore, I accept the constant teaching of the Popes on the cooperation of Church and State. None of this obliges me to accept that every decision made by Pius IX as head of the Papal States in the Good Old Days was a good one, nor that all the policies of the Papal States were good and just. The whole point of being Traditional Catholics is that we are not slaves of the daily thoughts and doings of Popes. We are not Ultramontanists. It would be silly to reject Ultramontanism about the post-Conciliar Popes and adopt it for the pre-Conciliar ones. We can leave that kind of inconsistency to liberal and conservative Catholics.

Popes have made many mistakes over the centuries. Some of their foreign policy decisions were disastrous, as anyone who reads any history can see. Their internal policies are no more impeccable. I labour the point because, really, we are at complete liberty to assess the civil laws and temporal policies of the Papal States without fear of undermining the Faith.

Is this, then, not about the Faith directly? No, it isn’t. It is about the exercise of temporal power in the Papal States. States routinely intervene in family life where the good of members demands it. This interference is sometimes absolutely necessary, but it remains extremely important that it is kept within strict limits. The integrity of the family in general, and the rights of parents over children in particular, do not exist at the pleasure of the state: as the Church has consistently taught, they predate the state and their prerogatives cannot be overridden by the state.

In this case, the justification for overriding the rights of parents over a young child was that the child had been baptised. It is perfectly true that baptism places a person under the jurisdiction of the Church: it gives the Church certain rights over the person, and gives the baptised person certain obligations towards the Church. It is also perfectly true that the State can and should enforce some of these rights and obligations on behalf of the Church, where this is necessary. Thus the duty of Catholics to provide financial support to the Church, to observe various rules about marriage, and so forth, could be, in Catholic states, determined in cases of dispute by Church courts, whose judgements could if necessary be enforced by agents of the state. The cooperation of Church and State was particularly seamless in the Papal States, but the distinction still existed. What is important to note is that the Church would not, obviously, attempt to enforce such obligations against non-Catholics, of whom the most prominent examples in Catholic states has historically been members of various Jewish communities.

This is where the Mortara case becomes interesting. The child may have been baptised, but the parents most certainly had not been. The duty of baptised parents or godparents to raise a baptised child in the Faith were not being violated by these parents: they had no such obligation. It was to fulfil the child’s right to a Catholic upbringing that he was removed from his family. No one claimed that the parents had done anything wrong.

The right to a Catholic upbringing is violated, however, by every nominal Catholic family, and come to that by baptised non-Catholics, who fail to educate their children in the Faith as they should. No doubt in some cases this did lead to state intervention, though I fancy not under that description: I mean, the civil authorities would have found places in orphanages for children whose parents were dead, insane, or otherwise incapable of bringing up their children in a reasonable way. The problem is that while the Church would have greater justification for demanding state intervention in cases where the parents are baptised, but it would appear that in such cases there is actually far more reluctance to intervene. Only in the most extreme cases would children be taken from their baptised parents: no one in the Papal States was demanding small children from parents who had, for example, simply lapsed. Something strange is going on here.

I’m afraid the strange thing going on is the attitude towards the Jews. I don’t want to engage in any kind of self-flagellation, but it is a historical fact that the treatment of the Jews in Catholics countries has not always been just, and since we do not think Popes are impeccable there is no a priori reason to think the shadow of such injustice should not have fallen on the Papal States. The civil law and policy applied to the Mortara family placed Jews in a specially disadvantageous position, compared to other families who might be failing to bring up their baptised children right, and I do not see the moral or theological justification for this special treatment.

As with the sex-abuse scandals, it is relevant to point out the wider context: in this case, that Jews were in many cases protected by Church teaching and Papal policies; that Protestant theology and Protestant states have been problematic in this area to say the least; and that the worst anti-semitism of all time has come from an ideology--Nazism--also hostile to Christianity. But it remains important not to let our Catholic amour propre blind us to the seriousness of the historical problem inside the Church, lest our failure to recognise or criticise it cause more scandal.

But there is something else as well. As I have noted, this is about the use of State power: the temporal arm of the Papal States. It seems Stephen Spielberg is planning to make a film about the Mortara case. Is he going to make a film about the Johanssen case, when Swedish social services kidnapped a home-schooled Christian child? Is he going to make a film about UK social services attempting to meet targets for the number of children taken into care, and the secret family courts which cannot be reported in the press, which have become a national scandal? Is he going to make a film about the Romeike family, which fled from Germany because social services there were likely to abduct the children for the crime of being home-schooled, who sought and gained asylum in the USA until they were very nearly forcibly repatriated by the lovely President Obama?

I don’t think so.

Please note, gentle reader, that today's debate about family policy does not have liberals on the side of the rights of the family, and the wicked old Catholic Church on the side of the state’s right to snatch away children who, in the eyes of some petty functionary, would do better in care. No, it is liberals who have the second attitude, and it is the teaching of the Church which supports the former. The Mortara case is a case in which the Papal States had slipped into a way of thinking and acting which is today characteristic of liberals. Defenders of Pope Pius IX, please note.

See also: Position Paper on the Good Friday Prayer for the Jews; and see the corresponding label in this blog.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

LMS Latin Course booking open

|

| Fr Richard Biggerstaff celebrating the Vetus Ordo in the chapel of the Carmelite Retreat Centre for the Guild of St Clare Sewing Retreat last year. |

Resideintial Latin course for adults 30th July to 3rd August 2018.

Since 2009 our intensive Latin course has helped a few dozen priests and laity to brush up their Latin for liturgical and scholarly purposes, in a Catholic atmosphere and with daily Traditional Mass.

Now it is taking place in a more accessible venue with more space and lower costs. Don't miss out!

Prices:

Full price is £340 (+ £30 optional single room supplement); without accommodation £290.

LMS Member £290 (+ £30 optional single room supplement); without accommodation £240.

Clergy, students and Seminarians full price £240 (+ £30 optional single room supplement); without accommodation £190.

Clergy, students and Seminarians LMS member £190 (+ £30 optional single room supplement); without accommodation £140.

|

| Some Latin Course students with Fr Richard Bailey last year. |

Dominican Rite High Mass for St Thomas Aquinas in Oxford, 27th Jan

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Catholic Medical Association 10th March, with me

The Catholic Medical Association invites all juniors and students of the healthcare professions (doctors, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, AHPs...), and all young people involved in the pro-life movement, to our next youth (18-35 years old) conference, entitled “Catholics in Healthcare: Men and Women of Conscience”.

Tyburn Convent, London. 11:15am registration. The conference will commence with Holy Mass (Missa Cantata) and talks will follow on The English Martyrs by one of the Tyburn nuns, Dr Joseph Shaw on conscience in healthcare and Dr John Smeaton (SPUC) on abortion and conscience.

Entry £10 donation, includes lunch, all profits to Tyburn Convent.

Sign up via event page on Facebook and EventBrite. Search “CMA England and Wales”.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Vermeule's mistake about human traditions

Adrian Vermeule has written a very interesting and in some ways helpful article in the Catholic Herald about the the nostalgia felt by a number of conservative/ traditionalist-leaning Catholic writers for the apparant live-and-let-live harmony between the Church and the 'liberal' state in the USA and elsewhere in the past, recent or not quite so recent. (I'll come to my disagreement with him in a minute.)

His argument is simply that liberalism is an ideology inherently hostile to the Faith with which no long-term, stable compromise is possible. He is absolutely right. As he writes:

Put differently, as I have argued elsewhere, the main “tradition” of liberalism is in fact a liturgy, centred on a sacramental celebration of the progressive overcoming of the darkness of bigotry and unreason. To participate in that tradition, that liturgy, is necessarily and inescapably to commune with and be caught up into a particular substantive view of time, history, world and the sacred – the liberal view.

The same point can be expressed in a slightly different way, from a historical perspective, which was made clear to me by reading Edward Norman's Secularisation. Norman points out that the brief golden age in the UK with neither religious intolerance from the dominant religion, or secularist intolerance from a liberal state, was simply a momentary equalibrium of forces in the long decline of the influence of the formerly dominant religion (Anglicanism) and the long rise in the power and self-confidence of the liberal state. This golden age - more like a golden mini-second - has inspired absurd amounts of political theorising, but was simply a moment when Anglicanism was too weak to assert itself against others but still too strong to be pushed around.

Vermeule goes on to say that we should seek eternal habitations and not place our trust in princes, though he doesn't express it quite like that. Again, this is correct. But he draws a rather surprising conclusion from this. He writes:

The typical mistake is to conflate the traditions of the Church with the traditions of the broader society. These are very different things; the Church is an ark afloat on a dangerous sea, which preserves its own internal traditions in part with walls that prevent it from being deluged by secular practices and mores. 1 Peter thus connects Catholic rootlessness and homelessness with a rejection of human political traditions, enjoining Catholics to “live out the time of your exile here in reverent awe, for you know that the price of your ransom from the futile way of life handed down from your ancestors was paid, not in anything perishable like silver or gold, but in precious blood …” Catholicism is not Burkeanism. Because Catholics are exiled in the world, they can ultimately have no attachment to man’s places and traditions, including political traditions.

I like the point that the Church has to protect itself from bad influences, but Vermeule makes a critical mistake in (apparantly) not considering the possibility that the political order be Christianised. Is this a possibility, he might ask? Well, Vatican II, in accordance with the whole tradition, demands that we at least try,

'to penetrate and perfect the temporal order with the spirit of the Gospel' Apostolicam actuositatem 5

And it would be rather strange if a society made up almost exclusively of believing Catholics should not, over several centuries, make some progress in this direction. Such societies have, of course, existed, and a glance at their political institutions and human culture in general confirms that, yes, with all the imperfections inevitable to fallen nature, they had made at least some progress. When considering the traditions of such societies, and the continuence in politics and general culture of these traditions in other societies which are not blessed with the same ideal conditions, does one really want to say that a Burkean respect for tradition has no value? Does one really want to say that no human traditions should be preferred to any other?

Even if there had never been any truly Catholic societies, even if one were presented with a choice between human traditions formed by pagan or secular societies, does one really want to say that we should not bother to respect and uphold the better, and oppose the worse? Do we really not care if polygamy and human sacrifice become the settled cultural expressions of the society in which we find ourselves, when we could work to preserve those cultural aspects of, say, Roman paganism, or modern liberalism, such as contain at least a fumbling and imperfect respect for the family and for human life, and which genuinely intersect with the Natural Law?

Vermeule's mistake is to extrapolate from a rightly pessimistic view of fallen nature, which is found throughout the Catholic tradition, to an implicit rejection of the possibility that nature can be redeemed. For the story with human culture parallels the story of human nature itself, since culture is the result of many humans living together. Fallen human nature is dominated by sinful desires, but it is not wholly evil: it is still capable of perceiving the moral law to some extent. Among pagans we find pity, honour, an appreciation of beauty, artistic and intellectual acheivements, and sincere religious aspirations. These good aspects of pagan societies are manifested in their traditions - as well as bad things.

Humans can, moreover, be redeemed, and this redemption has the effect of beginning a process of freeing them from error and confusion, allowing them to live better, if not perfect, lives consistently, allowing them to think more clearly, allowing them to undertake art and politics and everything else in ways less in slavery to sin. This has consequences for human traditions, for politics. The disappearance of redeemed humanity from the political and cultural scene has the contrary consequences. Listen to the popes:

…where religion has been removed from civil society, and the doctrine and authority of divine revelation repudiated, the genuine notion itself of justice and human right is darkened and lost…

Pius IX Quanta Cura §4

And

Therefore the law of Christ ought to prevail in human society and be the guide and teacher of public as well as of private life. Since this is so by divine decree, and no man may with impunity contravene it, it is an evil thing for any state where Christianity does not hold the place that belongs to it. When Jesus Christ is absent, human reason fails, being bereft of its chief protection and light, and the very end is lost sight of, for which, under God's providence, human society has been built up. This end is the obtaining by the members of society of natural good through the aid of civil unity, though always in harmony with the perfect and eternal good which is above nature. But when men's minds are clouded, both rulers and ruled go astray, for they have no safe line to follow nor end to aim at.

Leo XIII Tametsi Futura §8

Should we feel more at home in a society still visibly shaped by Christianity, with saints' names and religious holidays, with respect for property and some grasp of natural justice, than we would be under Nazism or Soviet Communism? Should we, finding ourselves in one of the latter societies, look back with nostalgia on the Christian past, and use the memories and traditions of that past, which still have resonance and force with our unbelieving compatriots, as part of a programme of resistance to evil and of restoration?

You bet we should.

By all means be pessimistic about the direction society is going in as Christ is rejected more and more completely. But don't repudiate your civic obligations, and don't repudiate those traditions and that past which are among our most effective means of evangelising those with whom we share, like it or not, a public culture. Neither of those repudiations are things we can 'afford', Mr Vermeule.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Prior of Norcia to celebrate Candlemas in London

Those interested in the Benedictines of Norcia will like to hear that Prior Benedict Nivakoff will celebrate a Sung Mass in Our Lady of the Assumption, Warwick Street, in London, at 6:30pm on Friday 2nd February, the feast of the Purification of Our Lady (Candlemas).

Prior Benedict succeeded the founder, Prior Cassian Folsom, in 2016, as I noted on this blog here.

More details about the Mass to follow.

|

| Now-retired Prior Cassian Folsom celebrating Sung Mass in Our Lady of the Assumption in May 2016 |

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

First Saturdays in the London Oratory

The Fathers of the London Oratory are extending the practice they adopted for the centenary year of the Fatima apparitions, of celebrating a Traditional Mass on the First Saturday of each month, at 11am, usually at the Lady Altar (on the right near the front). The first one of the New Year is on Saturday 6th January.

More information about the devotion, recommended by Our Lady at Fatima, below the fold.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Scottish Chartres Chapter

I'm delighted to pass this on from Una Voce Scotland. The Scots have had their own 'chapter', a segment of the huge column of pilgrims, on the Chartres Pilgrimage, for a few years now, often supported by the Sons of the Holy Redeemer (the Papa Stronsay Redemptorists), who created this 'Bonny Prince Jesus' image (and had it authorised for public use). This year they are joined by the indefatigable Fr Michael Rowe who was the Chaplain of the Latin Mass Society's Walsingham Pilgrimage in 2017.

I'm delighted to pass this on from Una Voce Scotland. The Scots have had their own 'chapter', a segment of the huge column of pilgrims, on the Chartres Pilgrimage, for a few years now, often supported by the Sons of the Holy Redeemer (the Papa Stronsay Redemptorists), who created this 'Bonny Prince Jesus' image (and had it authorised for public use). This year they are joined by the indefatigable Fr Michael Rowe who was the Chaplain of the Latin Mass Society's Walsingham Pilgrimage in 2017.

The contact email address is fromscotlandtochartres@gmail.

There is also a Facebook page.

The Chartres Pilgrimage (17th-21st May 2018) is something everyone attracted by the Traditional Mass should do - the younger the better, but if you are reasonably active, or can make yourself so by May, then you have no excuse not to.

Here are some practical details.

The Bonnie Prince Chapter - Chartres 2018

with Chaplain Father Michael Rowe

Full programme

(as at 15th December 2018)

Thursday 17th May

1830 Depart Edinburgh airport (Easyjet flight) to Paris

2120 Arrive Paris Airport Charles de Gaulle

Stay in Hotel Gay-Lussac, Rue Gay-Lussac, Paris 75005

Friday 18th May

840 am Traditional Latin Mass at Chapel of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal, Rue du Bac, Paris

Breakfast

Visit to the Shrine of Saint Vincent de Paul and the Chapel of the Passion

Picnic lunch

Visit to Our Lady of Victories and Basilica of the Sacred Heart (Sacre Coeur) Early dinner in restaurant near hotel

Bed (10pm curfew!!)

Saturday 19th May (vigil of Pentecost)

6 am walk to Notre Dame de Paris for start of Notre Dame de Chrétienté pilgrimage

Sunday 20th May (Pentecost Sunday)

6am Continue on Notre Dame de Chretiente pilgrimage

Monday 21st May (Pentecost Monday)

Arrive at Basilica Notre Dame de Chartres Dinner in restaurant in Chartres

Stay in Hotellerie Saint Yves, Chartres

Tuesday 22nd May (Pentecost Tuesday)

8am Traditional Latin Mass, Basilica Notre Dame de Chartres

Breakfast

Visit Basilica Notre Dame de Chartres

Return on train to Paris

Lunch

1740 Depart Paris Easyjet

1825 Arrive Edinburgh

COST Flights

Each person books their own Easyjet return flight - prices change but at time of writing the price is

£69 return

Hotel costs

Hotel Gay-Lussac, Paris, for 2 nights - the price varies from £68 per person to £154 per person depending on the room type you choose.

Hotellerie Saint Yves, Chartres for 1 night the price is £30 per person for sharing a twin or triple room.

The cost of the Notre Dame de Chrétienté pilgrimage is approximately £40 which includes bread and soup and 2 nights accommodation (a communal tent)

BOOKINGS CONTACT : Mrs Julienne Thurrott fromscotlandtochartres@gmail.com

Bookings close 15th APRIL 2018

THERE ARE A LIMITED NUMBER OF GRANTS OF £100 AVAILABLE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE. CONTACT fromscotlandtochartres@gmail.com if you would like to apply for a grant.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Statement on Amoris by Bishops of Kazakstan

This document speaks for itself; I post it here in full.

-------------------------------

about sacramental marriage

The mentioned pastoral norms are revealed in practice and in time as a means of spreading the "plague of divorce" (an expression used by the Second Vatican Council, see Gaudium et spes, 47). It is a matter of spreading the "plague of divorce" even in the life of the Church, when the Church, instead, because of her unconditional fidelity to the doctrine of Christ, should be a bulwark and an unmistakable sign of contradiction against the plague of divorce which is every day more rampant in civil society.

• "With regard to the very substance of truth, the Church has before God and men the sacred duty to announce it, to teach it without any attenuation, as Christ revealed it, and there is no condition of time that can reduce the rigor of this obligation. It binds in conscience every priest who is entrusted with the care of teaching, admonishing, and guiding the faithful "(Pius XII, Discourse to parish priests and Lenten preachers, March 23, 1949).

As Catholic bishops, who - according to the teaching of the Second Vatican Council - must defend the unity of faith and the common discipline of the Church, and take care that the light of the full truth should arise for all men (see Lumen Gentium, 23 ) we are forced in conscience to profess in the face of the current rampant confusion the unchanging truth and the equally immutable sacramental discipline regarding the indissolubility of marriage according to the bimillennial and unaltered teaching of the Magisterium of the Church. In this spirit we reiterate:

Being bishops in the pastoral office those, who promote the Catholic and Apostolic faith ("cultores catholicae et apostolicae fidei", see Missale Romanum, Canon Romanus), we are aware of this grave responsibility and our duty before the faithful who await from us a public and unequivocal profession of the truth and the immutable discipline of the Church regarding the indissolubility of marriage. For this reason we are not allowed to be silent.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.