Chairman's Blog

LMS Pilgrimage to Aylesford, 1st October

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

LMS Tyburn Walk 2016

In 2014 the Latin Mass Society organised a devotional 'walk' from the site of Newgate Prison to the site of the Tyburn Tree, the gallows where prisoners from Newgate were executed, among them at least 105 Catholic martyrs. We didn't manage to do it last year, but it happened on the Bank Holiday Monday this week, while I was still in Walsingham. Here are some pictures, thanks to @idlerambler.

In 2014 we had 45 people with us; this year, there were 70. Also, this year we had Low Mass in Tyburn Convent, build near the site of the Tyburn Tree, which was a great privilege.

The walk was led by Fr Mark Elliot-Smith of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, who is based nearby in Our Lady of the Assumption, Warwick Street.

The above is St Patrick's, Soho Square, which is close to the route. And below is Tyburn Convent.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Walsingham 2016: Photo essay

I took very few photos this year, since John Aron was taking lots; I've included some of his below.

In a nutshell, the LMS Walking Pilgrimage from Ely to Walsingham was a great success, with lots of people, lots of prayers and songs, and lots of graces. And lots of children.

We had with us Fr James Mawdsley FSSP, now at St Mary's, Warrington, and Fr Michael Rowe from Perth in Australia, who has been with us twice before. We were able to have High Mass with the help of Br Anthony of the Friars of Gosport, who is awaiting ordination. We also had a Fraternity seminarian, the Rev Mr Thomas O'Sullivan, very well known to me from his Oxford days; he was MC at our masses, another Gosport Friar, Br Philomeno, who has done the pilgrimage before, and a lay brother of the Society of St Vincent Ferrer, Br Vincent Hoare, who sang with our small schola.

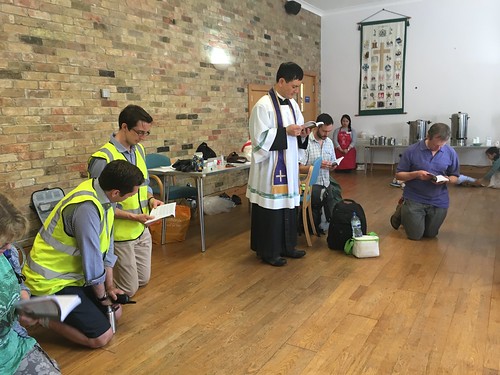

The Blessing of Pilgrims from the Roman Ritual.

Did I mention there was also lots of walking? About 58 miles, in fact. The weather was on the hot side, but nothing too extreme.

Mgr John Armitage, Shrine Custodian at the Catholic Shrine, received a First Blessing from Fr Mawdsely, who was ordained in June.

The Shrine has been given the status of Minor Basilica since our last visit.

For our big Mass on Sunday and the Holy Mile and our devotions at the site of the Holy House, we were joined by lots of people who were there for the day, and people from Youth 2000, which takes place the same week.

Fr Rowe celebrated the Sung Mass we always have on the Monday following the pilgrimage in the Slipper Chapel.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Succesfull walking pilgrimage in Scotland

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Why they hate us

This has already done the rounds in the media, but I'd not seen one particular aspect pointed up. The slick propaganda magazine of the Islamic State (ISIS), Dabiq, has a chilling article entitled 'Why we hate you and why we fight you'. You can see this hideous publication here; the article starts on p30. They hate us, they say, for three reasons: for our Christianity, for our liberal secularism, and for Western foreign policy. They emphasise the point that the last issue is not the primary one.

To illustrate the West's secular liberalism they display a photograph of a pro-gay marriage demonstration. To illustrate the West's wrong-headed religious tradition they have a photo of... the Traditional Catholic Mass. The Altar Cards allow no room for doubt.

It reminds me a story I heard a few years about about the late, lamented magazine The Sower, of the Maryvale Institute. They had an article about the Mass which they wanted illustrated with appropriate photos. The non-beleiving designer did a search for photos and most of them turned out to be of the Traditional Mass. He just thought they looked nice. This didn't help The Sower which was gaining a reputation for being a bit too orthodox.

What does it tell us, that non-beleivers, whether sympathetic or ferociously unsympathetic, pick out the Traditional Mass as illustrative of Catholic liturgy, or even of Christianity as a whole? The Mass in its traditional form looks the part. It looks like worship. It corresponds to their vague and perhaps confused notions of what Christian worship is. When an atheist or a Muslim extremist thinks of Christianity, this is a prominent mental image.

It means that if we can explain what is going on in this picture, we are addressing the heart of their idea of our religion. In clearing away misunderstandings and perhaps hatred of this, we will be cultivating a plant already rooted in their minds.

That really is something worth considering.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Video interview with Fr Anthony Mary F.SS.R

Fr Anthony Mary is one of the older generation of priests of the Sons of the Most Holy Redeemer, the traditional 'Transalpine Redemptorists' based on Papa Stronsay in the Orkneys. They also have an apostolate in Christ Church, New Zealand, where Fr Anthony is currently based.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Fr Armand de Malleray FSSP on Fr Rolheiser

|

| Michaelangelo's 'common misconception' |

Not for the first time, Fr Armand de Malleray has written to correct a school-boy error on the part of Fr Ronald Rolheiser in the Catholic Herald. For my money, Fr Rolheiser's articles are the next-worst source of theological error in the dead-wood Catholic media in the UK after those of Mgr Basil Loftus. How a priest of good will could have failed to grasp the fundamental reality of the doctrine of hell as a point of no return is mystifying, but that is what he has done. He even presumes to correct the teaching of our Lord in the Gospels, writing as follows.

And yet, the Gospels can give us that impression. We have, for example, the famous parable of the rich man who ignores the poor man at his doorstep, dies, and ends up in hell, while the poor man, Lazarus, whom he had ignored, is now in heaven, comforted in the bosom of Abraham. From his torment in hell, the rich man asks Abraham to send Lazarus to him with some water, but Abraham replies that there is an unbridgeable gap between heaven and hell and no one can cross from one side to the other. That text, along with Jesus’ warnings about that the doors of the wedding banquet will at a point be irrevocably closed, has led to the common misconception that there is a point of no return, that once in hell, it is too late to repent.

Yes, it has led to that impression: because that is the teaching of both Testaments of Scripture, the Fathers and Doctors, and of the whole Church.

Fr de Malleray's letter is as follows. (Catholic Herald 19th August 2016)

Sir,

Fr Rolheiser deplores "a common misconception...that once in hell it is too late to repent" (August 12). But Francis told mobsters the opposite: "There is still time not to end up in hell, which awaits you if you continue on this world." This would be a bad joke, rather than a fatherly and solemn warning, if hell were not a permanent destination. The Catechism confirms: "To die in mortal sin without repenting and accepting God's merciful love means remaining separated from Him for ever by our own free choice. This state of definitive self-exclusions from communion with God and the blessed is called "hell" " (#1033).

Fr Rolheiser rightly stresses that God's mercy knows no bound, so that if a damned person showed the least sign of contrition, God would responde. But precisely, the Church clearly teaches that once our soul departs from our body, our time to merit -- or demerit -- is ended, so that we cannot become better or worse. Consequently, the soul of a damned person is utterly incapable of regret or love, and it will never want to improve, whatever God may try. How seriously then should we take our time on earth, since it determines our eternity!

Yours faithfully,

Fr Armand de Malleray, FSSP

Warrington, Cheshire

It is mystifying that the Catholic Herald continues to give Rolheiser a platform. Letters correcting his fundamental errors are published a few times a year, but have no effect on him, no dount in part because it is a syndicated column which appears in a number of Catholic publications, and can be read on Rolheiser's website. Does that make it cheaper than a specially commissioned article, I wonder?

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Islamic terrorism: What can we do?

Here, there is something which can be contributed by people who still believe in something, something wholesome and historically rooted. Self-doubt and self-flagellation, even when offered by Christians, has nothing to offer the West; these are things already widespread in our societies. What we can offer is something substantive: that life, beauty, and God are real and have value, are worth something, and can give shape, discipline, and meaning to our lives. If Westerners really believed these things, and set themselves in their lives to live accordingly, then the Islamists would not be confronting such an easy and open target.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Walsingham Pilgrimage preparations

I've just ordered 80 copies of the LMS Pilgrims' Booklet for the LMS Walsingham Pilgrimage.

If you're now coming, you are missing out! But we'll put up some reports on social media as we go along.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

New Mass of Ages available

The autumn 2016 edition is now available in which we publish part of the talk given to the AGM by Archbishop Thomas Gullickson, Apostolic Nuncio to Switzerland and Lichtenstein. Speaking on the subject ‘The persecution of the Church’, Archbishop Gullickson said:

The autumn 2016 edition is now available in which we publish part of the talk given to the AGM by Archbishop Thomas Gullickson, Apostolic Nuncio to Switzerland and Lichtenstein. Speaking on the subject ‘The persecution of the Church’, Archbishop Gullickson said:

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.