Chairman's Blog

LMS Walsingham Pilgrimage: photos

|

| Approaching the Priory grounds at the end of the Holy Mile. |

|

| Mass in Cambridge on Thursday morning for the three pilgrims trying out an extra leg of the walk: another 18.4 miles, to Ely |

|

| Pilgrims' blessing from Fr Serafino Lanzetta. |

|

| On the road by the Great Ouse. |

The chapel at Oxborough is undergoing repairs and the lovely reredos is covering in a dust sheet.

|

| In the Reconciliation Chapel at the Catholic Shrine on Sunday. |

|

| The Holy Mile from the shrine to the site of the Holy House in the Priory ruins |

|

| In the Priory grounds |

|

| Mass on Monday for those who had stayed overnight. |

|

| An expanded cooking and support driving team rose magnificently to the occasion! |

Support the Latin Mass Society

Latin Motto from Mass of Ages

Dulcis agonista tibi convertit domus ista Pancrati memorum precibus memor esto tuorum

What does pastoral care look like?

|

| The Traditional Mass behind bars: so to speak. The Oxford Oratory. |

…this Dicastery is of the opinion that this [permission] would not be an opportune decision. Therefore, we deny the request. The path established by the Holy Father in Traditionis custodes is quite clear and this has been underscored both in the “Letter to Bishops of the Whole World” which accompanied the Motu proprio and in the Responsa ad dubia of this Dicastery, which were personally approved by the Holy Father. In this latter document, with regard to this very point, it was highlighted that the liturgical reform of the Second Vatican Council “has enhanced every element of the Roman Rite and has fostered – as hoped for by the Council Fathers – the full, conscious and active participation of the entire people of God in the liturgy (cf. Sacrosanctum Concilium no. 14), the primary source of authentic Christian spirituality”. Most recently the Holy Father’s Apostolic Letter of 29 June, Desiderio Desideravi, on the liturgical formation of the people of God, expands on the above mentioned letter to the bishops and reaffirms Pope Francis’ desire that unity around the celebration of the liturgy be re-established in the whole Church of the Roman Rite (n. 61).

There is of course no difficulty for Fr [] to celebrate Mass according to the editio typica tertia (2008) of the Missale Romanum.

The Morning After Pill: abortion or contraception?

My latest on Catholic Answers wades into some of the complexities about the 'Morning After Pill', aka 'Emergency Contraception'.

It begins:

Recently, a spokesman for the bishops of Louisiana suggested that the use of so-called “emergency contraception” is compatible with Catholic teaching in cases of rape. The news article reporting this connected it with the explicit exception made for “emergency contraception” in the restriction of abortion by new Louisiana abortion laws, made possible by the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade. There are, however, a tangle of issues here that I will try to separate.

The Catholic Church teaches that human life is worthy of protection from the moment of conception—the moment when the genetic material of an ovum and of a sperm are united to form a new human (see the Catechism of the Catholic Church 2270 and following). The Church, further, demands that this life be protected by law (2273).

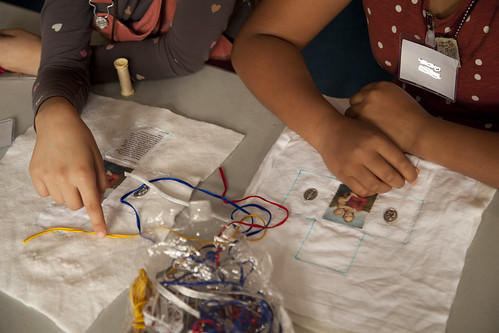

SCT Summer School: Classes and activities

To this end we have five 40-minute lessons most days, as well as Sung Mass, Rosary, Compline, and activities. Most of one day was dedicated to a trip to Oxford, where we had Mass in the Oratory and a tour of some sites of particular Catholic interest.

The week includes a quiz on what the children have learned, and we had football and tennis in the afternoons.

Every year the children perform a staged reading of part of Dorothy Sayers' radio plays on the life of Christ.

To join the mailing list email info@stcatherinestrust.org; to make a donation see here.

SCT Summer School photos: liturgy

Support the Latin Mass Society

LMS AGM Mass: photos

Radio discussion with Fr Robert McTeigue SJ

You can hear my latest chat with Fr McTeigue SJ on his Catholic Current radio show here.

New video on the LMS Walsingham Pilgrimage

Part-time Job opportunity at the Latin Mass Society

|

| The current LMS Office, when it opened in 2009. |

- Office administration - The Office Assistant acts as the principal secretary for the LMS office.

- This includes general correspondence, answering telephone calls, post and emails.

- Membership administration - The Office Assistant is responsible for the membership database (CiviCRM), membership renewals, data entry, data analysis, data export (print or email mail-merges).

- Mail-order - The Office Assistant is responsible for the administration of the LMS online shop (Drupal Commerce). This includes stock replenishment, stock management, product updates/additions and order fulfilment (picking, packing & mailing).

- Information administration - The Office Assistant is responsible for compiling information which pertains to the Charity, including research and document publication and distribution.

- Volunteer administration – The Office Assistant is responsible for overseeing office work undertaken by volunteers.

- Other tasks as determined by the General Manager.