Chairman's Blog

Feast of the English Martyrs, Didcot

Fr Philip Pennington Harris, Parish Priest of the Church of the English Martyrs in Didcot, is celebrating his parish's Patronal Feast on Friday 4th May with a Traditional Missa Cantata. It will be accompanied by the Schola Abelis of Oxford. Join us!

The church is at 15 Manor Crescent, Didcot OX11 7AJ (click for a map).

Mass is at 7:30pm.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Pilgrimage in honour of the English Martyrs in Preston, Sat 5th May

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

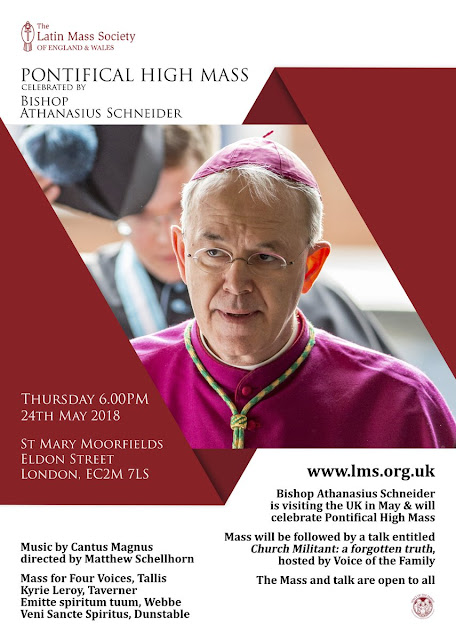

Bishop Schneider to say Mass in London 24th May

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

LMS Priest Training: private Masses

Another characteristic feature of these conferences are the private Masses. This time I was able to see not only private Masses before breakfast with one server, but others celebrated as a demonstration to priest participants.

We are very fortunate in this venue, Prior Park, since in addition to the High Altar there are four beautiful side-altars. Once upon a time, these would have been used daily by the priests teaching in the school. Today, it is wonderful to see them being used simultaneously as originally intended.

The chapels themselves are testimony to an attitude to the Mass to which the Latin Mass Society is devoted: that each celebration of Mass has great value. Even if there aren't many people there - even if there is no congregation at all - priests should want to celebrate Mass daily, and the Faithful should be glad to stipend them to celebrate for particular intentions. As the Congregation for Clergy recently reiterated, the priest's spirituality, the Holy Souls in Purgatory, and the good of the Church and the world are all advanced by each celebration of Mass.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

LMS Priest Training: training sessions

We are very fortunate in having many people with liturgical expertise, both clerics and laymen, willing to spend time training priests and servers in the ceremonies of the Traditional Mass.

Nothing could be a better use of the time and resources of the Latin Mass Society, and of our supporters and friends, than this training, especially as it is carried out by people who really know what they are doing. Not me, I should add: my contribution has been only to make a photographic record of it.

As I noted in the previous post in this series, this Training Conference was particularly well-attended: not like the very early ones, when we had forty priests turning up, the pent-up demand of decades, but well-attended all the same, notably by priests and seminarians and deacons who needed to learn the Mass from scratch.

We also had a lot of servers attending. The difficulty for some of them after this conference will be finding opportunities to serve and MC regularly at Sung and High Masses near them. What we have been able to do is have a bash at the chicken-and-egg problem of there not being occasions for local servers to gain experience of such Masses, and these Masses not being celebrated because of the lack of servers with experience.

This conference, like the last one, was also an opprtunity for our Musical Director Thomas Neil to rehearse quite intensively with his polyphonic choir, who were resident at the conference, and perform with them every day, Monday to Thursday. The music at the two Masses I attended was superb. This is another example of the building up of expertise, experience, and relationships which will bear fruit for many years to come.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

LMS Priest Training: public liturgies

I was able to attend the LMS Priest Training Conference for its final two days, on Wednesday and Thursday. In this post are photographs of the two High Masses of those days, celebrated respectively by Fr Thomas Cahill and Fr James Mawdsley FSSP.

Prior Park is an independent Catholic boarding school (on holiday last week). The splendid chapel, dedicated to Our Lady of the Snows, was built by Bishop Baines in 1830, when the site was intended to be a seminary.

The Priest Training Conference this year was one of our most successful, and the third to take place at Prior Park. Because of the early Easter last year we were unable to book it for the Easter holiday and it didn't take place. That problem will recur next year; however the demand for places this year means that we may look for an alternative venue.

This year's Conference was attended by priests from seven dioceses, plus the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, four seminarians and two permanent deacons. We also had a good number of trainee servers.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Bishops have become strangers to each other: here’s why

|

| The Tower of Babel (Wikipedia Commons) |

Here's the feature article of mine published by the Catholic Herald last weekend. It's not on the website.

----

|

| St Giovanni Calabria. His correspondance with C.S. Lewis has been published here. |

This year, Pope Francis promulgated a new document on seminary education, Veritatis gaudium. It demands, like its many predecessors, that future priests learn Latin: not for the liturgy, but to the far higher standard required for studies. The few seminarians who actually do get a bit of Latin can learn some interesting things. While modern Church documents are drafted in a vernacular language, they generally have to be translated into Latin to go into the Church’s official records. This seems to have become an opportunity for a final review of the contents: things are toned down or tightened up. This process came into public view when it was revealed that the first, French, edition of the Catechism of the Catholic Church took a significantly more accommodating line on lying than the later, but official, Latin version. On other occasions, a progressive spin has been given to texts when the official Latin is turned into English and other vernaculars: most notoriously with the documents of Vatican II, and with the ‘old ICEL’ translation of the Mass.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Some thoughts on Jordan Peterson

My favourite Anglican theologian, Alastair Roberts, has written in some detail on Jordan Peterson, and in order to get to grips with his thought from a Christian perspective I recommend reading this post of his at least. For the benefit of my own readers--and, as often on this blog, to clarify my own thinking--I want to take a different approach, and say something reasonably brief on why Catholics should welcome, in part, and disagree, in part, with the Peterson phenomenon.

For it is indeed, a phenomenon. Sometimes these things are shortlived but Peterson is, at least by social media standards, an intellectual heavyweight, which I think will give him greater staying power. In any case, he is influencing a lot of people, and I think that over the next decade we will increasingly encounter young people, particularly men, who have been influenced by him. It's really that which motivates me to write. So what is it all about?

There is a practical and a theoretical aspect to his work. The practical stuff is about how self-discipline and an aspiration to objective value is necessary to have a decent life, in combination with a refusal to go along with a number of politically correct ideas. This is underpinned by the theoretical aspect of his thinking. What I've seen of this can be summarised, very crudely, as 'Jung meets evolutionary biology', and it is this which I want to talk about here.

Jungians take mythology and religion very seriously as psychological phenomena: they regard mythical and religious stories and world-views as embedding deep truths about human traits and the human condition. This YouTube video of Peterson's about the Easter message shows how he does it. Thus, human socialisation involves establishing a reputation for generosity and engaging in reciprocity, and this can be taken to a higher level in sacrificing things in the present for the future. This can in turn be represented in terms of sacrificing things for the sake God, in the hope that God will be good to us in the future. This kind of psychologising interpretation can be applied across the Bible and indeed to other religious traditions.

The dangers with this should be obvious. It is simply indifferent to the historical basis of the stories. It equally says nothing about the metaphysical reality of the actors in these stories: i.e., whether God actually exists. It represents an open invitation to distort the Christian message for the sake of shoe-horning it into a favoured psychological theory: Jung himself famously interpreted the newly-proclaimed Dogma of the Assumption as raising Our Lady to membership of the Blessed Trinity. And it consistently leaves out the operation of grace: as Alastair Roberts points out, it is Pelagian. Unless you commit yourself to God being a real actor in the human story, you can't expect Him to intervene to help you out, even in the subtlest ways.

On the other hand, it is nice to hear someone talking about Biblical ideas with interest and respect, and by no means is all of the genuine message lost in Peterson's retelling. The mere fact that the Bible is being brought into the conversation is a huge opportunity for the Church, and we must be ready to engage with the interest Peterson arouses and correct what needs to be corrected. One of the interesting aspects of this is that Peterson's quest for his own brand of psychological insights leads him away from a historical-critical or liberal interpretation. Thus, when God asks Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, Peterson is not concerned to explain this away or ignore it. He says, rather: well, the real world is like that, isn't it? Sometimes you have to sacrifice what you are most attached to.

What Peterson is doing goes back to Kant, who looked for moral allegories in Scripture. Christ is the Ideal Man and so on. Kant's approach influenced the liberal tradition of interpretation which claims that brotherly love and the Golden Rule comprise the 'real message' of Jesus, and not any of that stuff about being God or sacrificial offerings. Peterson's interpretation is different, because his own moral outlook is different: and maybe because he's a bit more sensitive towards the authentic message of the Bible.

The Jungian stuff is, of course, also far from new, and one thing readers should be aware of is the weaknesses of Jungianism as a psychological model. Jung's standards of clinical research were abysmal, and if Freud's conclusions were sped by his cocaine habit, Jung tried to confirm his conclusions by dabbling in the occult. Both Freud and Jung made the fatal error of assuming that other people's psychologies were like their own, as Dr Pravin Thevasathan has pointed out in his CTS booklet on mental health.

Again, Modern students of mythology are prone to dismiss the whole whole world of psychological interpretation, which includes J. G. Frazer's Golden Bough, Joseph Campbell, T.S. Eliot, and Robert Bly, as being too dependent on selective reading and wishful thinking: they only find patterns by ignoring the bits which don't fit. The putative psychological insights, of course, must stand or fall on their own merits.

A related weakness of Jung is the theory of the collective unconscious. This is the idea that we all have similar or identical ideas at the backs of our minds, of the king and the witch and the mother and the dragon and what not, and it is not that these derive from experience and story-telling, but that the experience and story-telling are explained in large part by these 'architypes' already in our minds. Put explicitly this sounds pretty ludicrous, and so indeed it is. It ignores cultural differences, for one thing; more fundamentally, there is no mechanism for such ideas to be passed on from one generation to another, except by teaching.

To hear Peterson and other Jungians talking about first the development and then the mysterious passing on of complex cultural artifacts, such as the idea of the hero, is ultimately to listen to a fairy-tale.

But here, Peterson hopes, evolutionary biology can come to the rescue, at least in some part, by its claim that patterns of behaviour, as well as the length of our legs or the size of our brains, have been honed and developed by the demands of survival over thousands of generations. At this point Catholic readers shouldn't be too frightened off by the idea of the evolution of human nature, problematic though that can certainly be, because the role this idea has in the argument for present purposes is simply to reaffirm that there is such a thing as human nature. People are not just organic machines which can be programmed in infinitely many ways. No: we have instincts and aspirations built in, and there are therefore certain ways of living which work, which lead to happy individuals and communities, and others which just don't. Among the ways of living which are simply hard-wired into human nature, on this view, are some pretty old-fashioned thoughts about gender roles and - a particular theme of Peterson - social hierarchy.

So Peterson's Jungian psychology, turbo-charged with evolutionary psychology, is a friend of social conservatism. It reaffirms the importance of the stories, myths and rituals of our religion and culture. It underpins traditional models of the family and society. It teaches that traditional morality, self-restraint and self-sacrifice have value. In all cases the value these things are said to have is ultimately value for the self: for mental health, for happiness. One could see it as a kind of Aristotelianism, a civilised morality of virtue and happiness. All the time, the truth of our religious claims is left hanging. Peterson is an agnostic. But worse than that, the Jungian and other influences he exhibits prompt him to place meaning ahead of the outside world. Meaning is imposed on reality: this isn't subjectivism, however, because we are all imposing the same meaning, or at least something sufficiently similar, because of our shared human nature/ Jungian architypes/ evolutionary behaviour patterns.

Ultimately, Peterson and his disciples are trapped in a universe whose meaningfullness is, or could very easily be, the product of collective fantasy, perhaps driven by the imperatives of the evolutionary struggle. This may seem preferable to a universe whose lack of meaning is laid starkly bare, as it is for too many young people growing up without religion or culture. But it is a lot closer to it than may at first be apparent.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Family Retreat 2018: photographs

The St Catherine's Trust annual Family Retreat took place last weekend, led by two priests of the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, Canon Amaury Montjeand and Canon Scott Tanner. They were joined on Saturday by Br Albert Robertson who was subdeacon at High Mass.

As always it was attended by many children - more than ever, in fact. The retreat is structured to make it possible for families to attend to attend together.

Alongside the Retreat the Gregorian Chant Network has its Chant Training Weekend: the singers attending this sing at the Retreat's liturgies. The Chant was led by Chris Hodkinson and Matthew Ward.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

London Triduum Photographs

|

| Tenebrae |

I attended all of the Triduum in St Mary Moorfields, organised by the Latin Mass Society, this year, for the first time.

|

| Taking the Blessed Sacrament to the Altar of Repose on Maundy Thursday |

|

| Prostration on Good Friday |

|

| The Passion on Good Friday |

|

| The 'crowd' (turba) sung polyphonically by the crowd during the Passion |

|

| Revealing the Crucifix |

|

| Venerating the Crucifix |

|

| The Blessed Sacrament, from the Altar of Repose |

|

| Blessing the Paschal Candle at the Easter Vigil |

|

| Processing back into church |

|

| Candlelit interior during the Vigil |

|

| Newly blessed water for the baptismal font |

|

| Easter Vigil Gospel |

|

| Elevation |

|

| Final blessing |

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.