Chairman's Blog

Farewell, Pope Benedict: official statement of the LMS

|

| From Wikipedia Commons. |

Statement on the death of Pope Benedict XVI

The Latin Mass Society learns with deep sorrow of the death of the Pontiff Emeritus, Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger.

As a theologian, as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and as Pope, he made an outstanding contribution to the life of the Church, in ways which will continue to be felt far into the future.

Catholics attached to the Traditional Mass have a particular motive for gratitude towards him. In his writings before his election as Pope he laid indispensable foundations for the rehabilitation of the Church’s ancient Mass, which had been banished to a precarious existence on the periphery of the Church’s life, its supporters treated—as he himself expressed it—like ‘lepers’. As Pope, his Apostolic Letter Summorum Pontificum, which declared that the older Missal has never been abrogated, transformed attitudes towards it, and brought it back into the heart of the Church. For a generation of priests and laity, Pope Benedict’s action remains the decisive influence on how they see the question.

Pope Benedict’s public actions reflected a great sensitivity to the liturgy, a comprehensive mastery of theology, and an intellectual honesty and courage based on profound humility.

The Latin Mass Society will be organising a Requiem of suitable solemnity for Pope Benedict in due course.

Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Latin Mass Society: position open for Communications Officer

We have a vacancy for a Communications Officer

As a consequence of the impending departure of Clare Bowskill as the Society's Publicist/Communications Officer, we are seeking a replacement.

Clare has done outstanding work for the Society - often in difficult circumstances - during the time she has been with us and we are extremely grateful to her.

Working with the Society’s General Manager, Trustees, and local activists, the Communications Officer will develop a proactive communications strategy using social media and mainstream media to promote the Society, its events, and its campaigns, and to promote membership and fundraising. The Communications Officer will also be able to react to events and news stories affecting the Society, to present the Society’s position and protect its reputation.

Attendance at some key events is essential.

Status: Self-employed. Hours: variable, averaging 10 hours a week. Salary: £7,000 pa. It is envisaged that the Communications Officer will work mainly from home.

Main duties and responsibilities

• Maintain on the Society’s website and social media accounts a flow of news, announcements, videos, and developing resources pages

• Develop promotions for LMS events using different channels (advertising, press coverage, social media, flyers)

• Coordinate membership and fundraising campaigns

• Cultivate relationships with people in the social media and Catholic and secular press (e.g. Catholic Herald, EWTN, bloggers, Catholic journalists, prominent Catholics)

• Put the Chairman and/or leading members of the Society forward for interviews, provide quotations, or compose articles for various media

• Ensure that journalists, bloggers etc. are invited to our major events

• Evaluate the success of press and publicity activity to aid future planning.

The ideal candidate will demonstrate:

- Significant experience of managing digital communications across a variety of social media.

- Experience of preparing press materials including Press Releases and relevant media for publicity.

- A basic knowledge of graphic design for print and digital content along with basic video editing skills.

- Experience of working under pressure

- Experience of working independently and in a small team

- Excellent and persuasive interpersonal skills

- Creative written communication skills

- A good knowledge and understanding of the UK and international Catholic environment and the Traditional Latin Mass

Application by CV and covering letter (hard copy or email) to Stephen Moseling, General Manager, The Latin Mass Society, 9 Mallow Street, London EC1Y 8RQ stephen@lms.org.uk

Closing date for applications: Friday, 30th December 2022. Interviews will take place in London in January.

You can download a pdf of the job specification HERE.

The Traditional Mass at the Oxford University Catholic Chaplaincy

David Lloyd, Requiescat in pace

In paradisum deducant te angeli.

Support the Latin Mass Society

Bogle and Morello on the Monarchy

The article by our friend, Theo Howard, entitled Monarchy and the Great Silence, published here at OnePeterFive, contains assertions that we believe are serious errors, which misrepresent the true position of the British monarch, not least the late Queen Elizabeth II.

Truth should be the first concern of Catholic journalists and writers, and so we wish to respond to Howard’s piece in fraternal charity for the sake of the truth.

Firstly, from a practical perspective, it is our concern that Howard’s article could do real harm by having the effect of encouraging secular republicanism (the only actual alternative available today) through the spreading of untruths, and serve to sour relations between nationalists and monarchists, particularly in communities where the issue is sensitive and even explosive. After all, it was not long ago that our United Kingdom was in conflict within its territories, namely in Northern Ireland, precisely over the question of whether that part of the Kingdom ought to be under the Monarchy or under a republic.

Annual St Benet's Hall Requiem

The first time I proposed such a Mass, to the last Master of the Hall who was a monk, Fr Felix Stevens, refused to allow it in the Hall chapel. However, I tried again with his successor, and it became an annual event.

The deacon was Dom Stanislaus Mycka of Farnbrough Abbey; the subdeacon was Br Joseph of the London Oratory. Mass was accompanied with chant by the Schola Abelis under Daniel Tate.

Support the Latin Mass Society

A Reply to Cavadini, Healy & Weinandy

| Rubrics erased in the Reform |

Cross-posted from Rorate Caeli.

Throughout this article they keep repeating two fundamental misunderstandings of the movement for the Traditional Mass, misunderstandings which make their analysis and recommendations beside the point. It is a principle of academic discussion that before criticising a position one must first be able to summarise it in a way which would be acceptable to those who put it forward. In this, CHW have, I am afraid, completely failed.

The first misunderstanding is in the motivation of the movement. It is all the more remarkable in that they express their own understanding as their reading of a passage from Peter Kwasniewski which says something entirely different. Dr Kwasnieski, as CHW quotes him, says this:

If at all possible, we should avoid participating in a form of prayer that deprives the Lord of the reverence that is due to Him. The Novus Ordo systematically does this by having removed hundreds of ways in which the Church showed her profound reverence for the Word of God and the holy mysteries of Christ.

CHW comment:

Such critiques presume that the reformed rite must be an occasion of significant irreverence; there is little appreciation of the many celebrations of the reformed liturgy with profound reverence, feeding the souls of countless members of the faithful in parishes throughout the world.

CHW want the argument to be about celebrants and perhaps the congregation lacking a spirit of reverence. But this is not what Dr Kwasnieski is talking about. He refers to the Novus Ordo’s reformers having “removed hundreds of ways in which the Church showed her profound reverence”. An obvious example would be the removal of the genuflection by the celebrant before each of the elevations. The reverence of the celebrant is another issue altogether.

Nor does Kwasnieski deny that people can be spiritually fed by the Novus Ordo. Like me and nearly all adult members of the Traditional Movement, he was fed by it himself for many years before discovering the Traditional Mass. What he felt, on making this discovery, is what he says in this passage: that there are things in the texts and rubrics of the Traditional Mass which express more clearly the reverence due to God than are to be found in the Novus Ordo.

I think this is extremely hard to deny, and perhaps that is why CHW don’t want to engage with this argument. Traditionalists could supply them with a mountain of examples, and also point to the published words of liturgists in no way committed to the Traditional Mass who have made similar arguments on particular points. Cardinal Ratzinger—as he then was—thought that the silent Canon was preferable, more reverent, more conducive to prayer, than the Canon proclaimed aloud. He and Cardinal Sarah have said the same thing about worship ad orientem being preferable to worship versus populum. Non-traditionalist liturgists have published critiques of the reformed Lectionary, the reformed Offertory Prayers, the Novus Ordo Sign of Peace, the reformed manner of receiving Holy Communion, and many other things. What is more, the Holy See itself has accepted some of these criticisms, such as those about the way the Collects were edited. In the 2008 edition of the reformed Missal a whole lot of words and phrases which had been cut out of them by the Concilium were actually restored.

Are CHW going to attack all these people for rejecting Vatican II? For failing to maintain communion with the Church? For lacking a proper respect for ecclesial authority? For failing to read the signs of the times? I very much doubt it. It is only when these arguments are made by Traditionalists that they are wrong. But this is ridiculous. There can’t be one law for us and another for everyone else.

The second misunderstanding is about how Traditional Catholics define themselves. CHW claim it is by reference to the Rite they attend: for Trads, they say, “‘Church’ is now defined by which Eucharistic rite one attends.”

This is easily disposed of. Among Traditional Catholics, there is absolutely no sense that the ancient Roman Rite is the only “true” or adequate or reverent liturgical form. If this seems surprising, consider the attitude of Traditional Catholics towards the ancient Dominican Rite, the ancient Ambrosian Rite, or the Eastern Rites.

I can imagine CHW protesting: Oh this is not what we meant! No, indeed: you didn’t think your statement through, did you? Trads are not fixated on the Roman Rite. The other rites are not so easy for most of us to attend, but we think they are great, and express in a beautiful way the universality and genuine pluralism of the Catholic Church. Typically trads regret the loss of liturgical diversity following the Council of Trent, and lament the ‘Latinisation’ of eastern Rites both before and after Vatican II; again, it is among Trads that you will find enthusiasts for the revival of the Sarum Rite and the regional Rites of France.

Given that CHW’s statement as written is totally false, what is the defining feature of Traditional Catholics? It is what it says on the tin: we are concerned with tradition: the passing on down the generations of a living patrimony of prayer, as opposed to the artificial manufacture of liturgy by committee: to paraphrase Cardinal Ratzinger.

This may make CHW a little uncomfortable, but it should be obvious that the rupture in this process of handing on, which Ratzinger referred to and which is undeniable by anyone with any knowledge of the matter coupled with intellectual honesty, is a problem. It is a problem, perhaps, with no easy solution. But it is right for Catholics to see it as a problem, because reverence for tradition is part of what it means to be Catholic.

Let CHW come out and deny that, if they can.

The attack on the Seal of Confession

The Report of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) published in October recommends ‘mandatory reporting’ of child sexual abuse, explicitly including under this requirement the breaking of the seal of the confession: that is, revealing things disclosed during the Sacrament of Penance, something considered so serious for Catholic priests that it leads to automatic excommunication. The Report’s recommendation follows similar moves in parts of Australia: the states of Victoria and Western Australia have passed laws seeking to oblige priests to disclose the content of confessions if these include allegations of child sexual abuse.

It is difficult to avoid the impression that the IICSA, like the Australian Royal Commission before it, and Australian state legislators, are more concerned with striking a pose than with the practicalities of child safeguarding. Their highlighting of the seal confession, implicated in precisely zero cases of child sexual abuse around the world, is reminiscent of their grandstanding demands, during their gathering of evidence, to see persons and documents from the Holy See, without bothering with official channels.

Pontifical Canon: reprint available from the Latin Mass Society

Cross-posted from Rorate Caeli.

This is a very handsome presentation of the main texts of the Mass, with illuminated capitals, full-colour picture pages, and large font, particularly for the Canon itself, which will be of particular benefit to readers with poor eyesight. These features are unfortunately not found with the 1962 edition of the Canon Pontificale.

The Canon Pontificale contains the prayers said at the Altar, from the Aufer a nobis (which follows the Preparatory Prayers) to the Last Gospel, but not the Proper Prayers and Lections. This makes it a slim volume of about 120 pages, intended for the use of Bishops.

It also contains the text of the Rite of Confirmation, the Blessing of a Chalice, and a few other things, such as prayers for use by the celebrant in preparation for Mass and in thanksgiving after it.

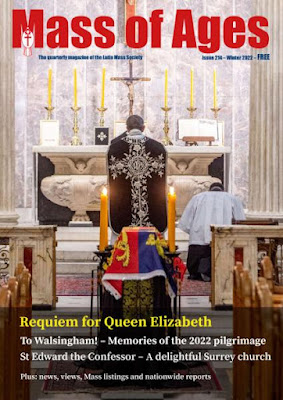

Mass of Ages Winter 2022 published

The Winter edition should be arriving with members right now: mine arrived today. It should also be in churches kind enough to stock it -- available free. It can be read online through the ISSUU website or app, optimised for use on mobile devices.

Details of the latest edition, and how to get a printed copy, here.

My favourite quote from the latest magazine is in Mary O'Regen's column, talking about devotion to the Holy Face. She quotes from the autobiography of Douglas Hyde, a communist who became a Catholic:

Hyde heard a Political Bureau member gripe that, “We get women into the Party…but within 12 months of our turning them into Marxists they are about as attractive as horses.” ... “The hatred which the Party kindles and uses is often quite shockingly apparent in eyes as hard as those of a Soho prostitute and lips as tight as those of a slumland money-lender.”

My favourite image is a very contrasting one: the charming carving showing St Anne surrounded by her daughters, with her grandsons playing below and their husbands in a row behind them. The is the subject of Caroline Farey's art history column this issue.

Our regular columnists:

• The Chairman’s Message: On why the Church must find a way of making peace with the Traditional Mass, which is to say, with her own heritage

• Family Matters: timely advice from James Preece on how when times are rough, we need to look out for each other

• Art and Devotion, Caroline Farey looks at a 15th century sculpture from South Germany

• Rome Report, Diane Montagna looks at some controversial appointments

• Architecture: Paul Waddington looks at the delightful church of St Edward the Confessor, Sutton Park in Surrey

• Mary O’Regan explains how to honour and love Our Lord’s Face is to have the gift of youthful beauty

• Wine: Sebastian Morello on the perfect accompaniment to treasured companionship

• World News: Paul Waddington reports on what’s happening around the globe

Support the Latin Mass Society