Chairman's Blog

Successful Latin Course from the LMS

Last week the Latin Mass Society's residential Latin Course took place. We were close to capacity in the venue, the Carmelite Retreat Centre at Boars Hill near Oxford. With the help of Matthew Schellhorn and a number of singers who were present as students Sung Mass was celebrated each day and Compline twice. The two priests who attended as students took turns with Fr John Hunwicke, who was teaching, to celebrate the Sung Masses, as well as Low Masses before breakfast.

The course is intensive, and the participants worked hard. But it was clearly also a lot of fun.

In addition to Fr Hunwicke, we had as a tutor this year Jean van der Stegen (top photo).

The dates for next year are already booked at the same venue: Monday 29th July 2019 to Friday 2nd August. Booking will open as soon as we've worked out the pricing.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

The death penalty for the prestige of the Papacy

I was asked for a quote by a journalist when the story broke; it was used by LifeSite here. I paste my full statement below.

'Catechisms are not usually regarded as magisterial documents in their own right, but as systematic summaries of magisterial documents. Their value lies in their accuracy as reflections of the Church’s perennial teaching. With this change by Pope Francis, the Catechism of the Catholic Church has become less accurate than it was before, since it is clear from both the teaching and the practice of the Church over two millennia, and the clear and consistent message of Scripture, that capital punishment is not incompatible with the dignity of the criminal, nor with his redemption.

‘The text recently published also appeals to contingent historical circumstances, such as the modern penal system. Such considerations, which apply in any case to some countries more than to others, are irrelevant to the question of whether capital punishment is always and everywhere wrong.

‘This development brings to a head the troubling question of whether the Holy Father’s theological advisers see themselves as bound by the definitive statements of past popes, including the well-known account of capital punishment given by Pope Pius XII. If they are not bound by past popes, there is no reason why future popes should be bound by this statement, and indeed the authority of Pope Francis over Catholics today is called into question.’

(See also my post about the death penalty here.)

The people online and in the media saying 'Well I've never liked capital punishment so I'm fine with this' are like the people who say, when there's a military coup and the rule of law is suspended and people are rounded up for imprisonment without trial, 'Well I never liked those people so I'm fine with this'. They are conceding something of permanent, strategic significance for something of transitory, tactical significance. They are selling their birthright for a mess of pottage.

Maybe they think that the wrongness of the Death Penalty is of fundamental significance, but even so it should be obvious that this way of winning the argument is not only self-defeating but is destructive of any possible future use of the prestige of the Papacy to win any argument inside or indeed outside the Church about anything. If Pope Francis openly contradicts Pope Pius XII, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith as recently as 2004, Scripture, the Fathers of the Church, and the entire Tradition, then the statement of a Pope, given a permanent place in the documents of the Church both in a speech recorded in L'Osservatore Romano and in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, ceases to have serious weight. Catholics and non-Catholics alike will cease to assume that such a statement is an authoritative emanation from an age-old tradition with normative force for the world's Catholics. It may as well be described as a passing, personal, political, foible. That is what I mean by the loss of the Papacy's prestige.

But wait! some will say: Aren't you going to see if the statement really is in contradiction with the immemorial teaching of the Church? No, that is neither necessary nor possible. Allow me to explain. Here is the money-quote of the new statement:

Consequently, the Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that “the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person”

The previous version of the Catechism told us:

the traditional teaching of the Church does not exclude recourse to the death penaltySince the new wording is not a simple grammatical contradiction of the old wording (as 'the traditional teaching of the Church excludes recourse to the death penalty' would be), then those so inclined may seek to interpret the new statement in some way which is not strictly incompatible with the old. So we have people saying things like this: what the new wording means is that in modern conditions the death penalty can never be used, and not that it is, like murder, per se malum ('evil in itself').

This is not the natural reading of the text, but one might argue that since it is purporting to represent the teaching of the Church we must read it if humanly possible in accord with previous authoritative statements of that teaching. On the other hand, bishops and theologians supposedly friendly to Pope Francis are loudly saying that the natural reading is the correct one: what modern conditions reveal is simply that the death penalty is never licit, never morally possible, because it contradicts human dignity.

We've been here before, have we not? This is the well-worn strategy of Amoris laetitia, and indeed of a lot of things since the Second Vatican Council. Flat contradictions with previous statements are avoided in official documents, but trumpeted by theologians and applied in practice by bishops, who are seldom corrected. This is no accidental ambiguity: it is a design feature. In this case the mouse-hole of ambiguity conservative Catholics need to crawl through to maintain the continuity between the two editions of the Catechism is humiliatingly small. When they have crawled through it, moreover, they will be ignored.

The argument about whether the new statement can be read in continuity with the old is, therefore, not something which can be settled: the ambiguity is inherent to the statement. What is clear is that this statement has been given the form of an official teaching of the Church, rather than just a prudential judgment, and that the purpose and effect of its promulgation is the undermining of belief in the binding and irreformable teaching of the Church that the death penalty is licit in some circumstances.

It is not necessary to settle the question of the precise meaning of the new statement, because whether it is read in a natural way or as being ambiguous makes no difference: in either case, Catholics must accept the constant teaching of the Church, the teaching well expressed in many documents of the Church over the centuries, not very well expressed in the old Catechism wording, and not expressed at all in the new wording.

In the meantime, as I have said, it is the prestige of the Papacy which is undermined. Whereas papal statements once had weight even outside the Church because they visibly expressed an ancient tradition, and could remind us all of truths which modernity was eager to forget, this is clearly no longer necessarily the case. Once we have digested this statement, there is nothing which the Pope will not be able to say to overturn other teachings, a corollary which those who reject other teachings of the Church have already pointed out. If the Papacy's prestige is totally destroyed, of course, it will not even be necessary for a pope to contradict statements made by his predecessors, because those statements will already have lost their force.

So that's fine and dandy, isn't it? If the power of the teaching of the Church is undermined, those things which that teaching have, however feebly, been holding back, such as theft, say, will be left unrestrained. It hardly matters that future liberal popes will not be taken very seriously when they say that theft is licit in certain subjective circumstances, if the old statements saying that it is never licit have themselves lost their power. If, as I have pointed out, liberalism is above all a negative, destructive, doctrine, then this is a win for liberalism. The things liberalism wants to destroy will be effectively undermined, and the positive, constructive project of conservatism will be crippled.

I think a lot of political strategy works by a kind of instinct, by habits of mind and associations of ideas. So I don't think this is necessarily the conscious plan of Pope Francis or anyone around him. What is clear is that he is not worried by the issue of visible continuity of teaching in the way almost all of his predecessors were. He's not worried about it because he's not worried about the consequences of obscuring this continuity, consequences those predecessors regarded as disastrous. He regards those consequences either as indifferent or positive.

This way of looking at things makes it harder for me to respond to the sincere and bewildered question: does all this mean that the Pope is a heretic, or even that his has lost his office? It is harder because I am not attributing to him clear-cut heretical intentions or indeed statements. But two things are clear. The first is that we have to continue to believe the teaching of the Church as authoritatively expressed down the ages. The second is that we have to continue to regard Jorge Mario Bergoglio as Pope for practical purposes unless and until some consensus or assembly of those with hierarchical authority in the Church declares that he has in some way 'deposed himself', in accordance with various theological theories on the subject. And no, that hasn't happened and is extremely unlikely to happen.

The confusion of this papacy cannot be wished away. Our task is to hold fast to the truth.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Historic crimes: repentance and reparation, Part 3

Reposted from September 2014

----------------------------------------------------------

In my last two posts I wrote about what our response can and should be to crimes, not personal crimes we have committed but those of the past (and for that matter of the present) which have, as it were, defiled the Church. Here I want to say a little more about the form reparation can take in practice.

|

|

Clockwise from top left: St Cuthbert Mayne, Bl John Nelson SJ,

who forgave the Queen as he was disembowelled, Bl Everard Hanse,

|

Here, again, is something relevant from Shakespeare. In his The Rape of Lucrece, Lucrece confesses her rape by Tarquin to her husband and father, and then commits suicide in front of them, plunging a knife into herself. Shakespeare describes what happens to her blood.

And bubbling from her breast, it doth divide

In two slow rivers, that the crimson blood

Circles her body in on every side,

Who, like a late-sack'd island, vastly stood

Bare and unpeopled in this fearful flood.

Some of her blood still pure and red remain'd,

And some look'd black, and that false Tarquin stain'd.

The idea here is that she did have some measure of guilt for what had occurred, and her death is a kind of expiation. It makes most sense, at least to a Christian reader, on Clare Asquith's reading: that Lucrece represents the English community, which in part remained faithful and in part apostatised under pressure from the Protestant Revolt. The shedding of the blood of the martyrs, which Shakespeare's description of Lucrece's suicide suggests, was a kind of expiation of the apostasy. The faithfulness of few, a faithfulness to death, in this way made up for the faithlessness of others. It makes the reconciliation of the whole country, the 'late-sacked island', more possible.

For the most part the English martyrs had no personal, guilty involvement with the despoliation of the Church and the persecution of the Faithful, but they offered their lives all the same for the salvation of all: for the guilty as for the innocent. Thus wrote St Edmund Campion to the Anglican establishment:

And touching our Society, be it known to you that we have made a league—all the Jesuits in the world, whose succession and multitude must overreach all the practice of England—cheerfully to carry the cross you shall lay upon us, and never to despair your recovery, while we have a man left to enjoy your Tyburn, or to be racked with your torments, or consumed with your prisons. The expense is reckoned, the enterprise is begun; it is of God; it cannot be withstood. So the faith was planted: So it must be restored.

|

||||

| Clockwise from top left: St Luke Kirby, B Robert Johnson, St Alexander Briant, B John Shert. Priests tortured (most of them at least) and then executed under Elizabeth Tudor. |

It is this spirit in which reparation must be undertaken: a spirit of pure charity. The hostile media reception of Catholic bishops, the jeers which greet the public wearing of the priestly cassock in some places, the quiet ridicule which greets large Catholic families: we aren't working to overcome these, we are working for the conversion of England. If that happens, of course, these things will disappear. But in the meantime we can offer them up for this intention.

Apart from the incidental sufferings of being a faithful Catholic in modern Britain, there are things which the Church enjoins upon us by way of reparation. Most familiar, perhaps, are the Divine Praises, which are said, as many hand-missals will explain, as 'Reparation for Profane Language'. In the same spirit, the Forty Hours Devotion was established as an act of reparation for the excesses of Carnival time.

Canons 1211 of the 1983 (current) Code of Canon law tells us:

More generally, the Tyburn Walk is done in a spirit of penance. We walked silently, without banners, in accordance with the long-standing tradition of the Guild of Our Lady of Ransom.

One of the innovations of the LMS Pilgrim's Handbook this year is the inclusion of the Seven Penitential Psalms, a devotion almost completely forgotten even by Traditional Catholics: and we did in fact sing some of them. The walking pilgrimages, to Walsingham, to Chartres, and others in Australia, Russia and America, are a wonderful opportunity for reparation.

In none of these cases does a penitential spirit mean a gloomy one: we perform these works of reparation with joy, like Juliet in Measure for Measure. The discomforts, inconvenience and - on the long walking pilgrimages, the pain - become positive when they are offered up in this spirit. At the same time, they don't stop being pains.

|

| Rosary Crusade of Reparation, 2014, about to start. |

Coming up on Saturday 11th October is an event which is perhaps unique today as being specifically advertised as an act of reparation: The Rosary Crusade of Reparation. It is one of the biggest public events in the Catholic year in London. About 2000 participants walk from Westminster Cathedral to the Brompton Oratory. The reparation is specifically for abortion. There ought to be an event like this every month in every diocese: but in the absence of that, do come along to this one.

The procession is led by a statue of Our Lady of Fatima, and we are reminded of the message of Fatima.

Penance! Penance! Penance! Pray to God for sinners.

|

| Rosary Crusade in Knightsbridge. |

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Historic crimes: repentance and reparation, Part 2

|

| Good Friday Liturgy with the FSSP, Reading |

Reposted from September 2014.

-----------------------------------------------------

In my last post, I suggested that what may be necessary in dealing with the crimes of our predecessors in the Church are two things: compensating the victims, and repudiating any ideological justification put forward for the crimes. My examples were anti-Semitism and paedophilia.

My discussion of past crimes has, deliberately, focused on issues where the crimes clearly really did take place, and clearly are crimes. I don't want to give the impression that I want to accept every accusation against Catholics as true: that will lead to injustice just as surely as treating every accusation as false. Nor am I, by any means, inclined to say that everything which has been done by Catholics down the centuries which does not meet the approval of modern liberals is a crime. Again, the hysteria surrounding the investigation of the recent past in Ireland shows that a lack of historical perspective, and extrapolation from insufficient information, can distort the picture to the extent that good people end up being depicted as monsters. Let us hope that the apology issued by the Associated Press news service over their own reporting of the Tuam excavations represents the high-water mark of this lunacy.

Plenty of crimes, however, are real enough; there is really no need to gild the lily. Looking at the child abuse scandal, for example, it is increasingly clear that it was a problem which affected a lot of institutions at a particular period of time, but that does absolutely nothing to excuse its presence in the Church. The seriousness with which this plague infected the Church is mind-boggling, and one may be excused for asking: what can possibly wash this from us?

I don't say: what will compensate the victims, or stop it happening again, or satisfy the courts, or even restore the Church's reputation. All these things are important, where possible, but there is also something deeper. These abominable crimes stick to the whole institution, they stick to us as Catholics, not because we are personally guilty but because they have, as it were, defiled the sanctuary. We hear some of the victims say: I can't bear to go into a church building, I can't abide being near a man dressed as a priest. It is not difficult to understand that. We need to purify the Temple as the Machabees purified it after the Abomination of Desolation.

The first thing I want to mention is shame. Shame, unlike guilt, is not necessarily personal; you can have family or national shame, as the converse of family or national pride. When appropriately directed, it is a good thing: any appropriate emotion is good. It is appropriate to feel ashamed of the Church in its human aspect, without losing sight of her divine aspect. The Church as a divine institution cannot be defiled, it is the Body of Christ and ceaselessly offers up to the Father the perfect Sacrifice. But it is human aspect it can be shameful, and the vituperation of a Savoranola or a Dante, directed even towards the holders of her highest offices, is sometimes justified. Whether they would have found the words to address the current crisis I do not know. But we should feel ashamed.

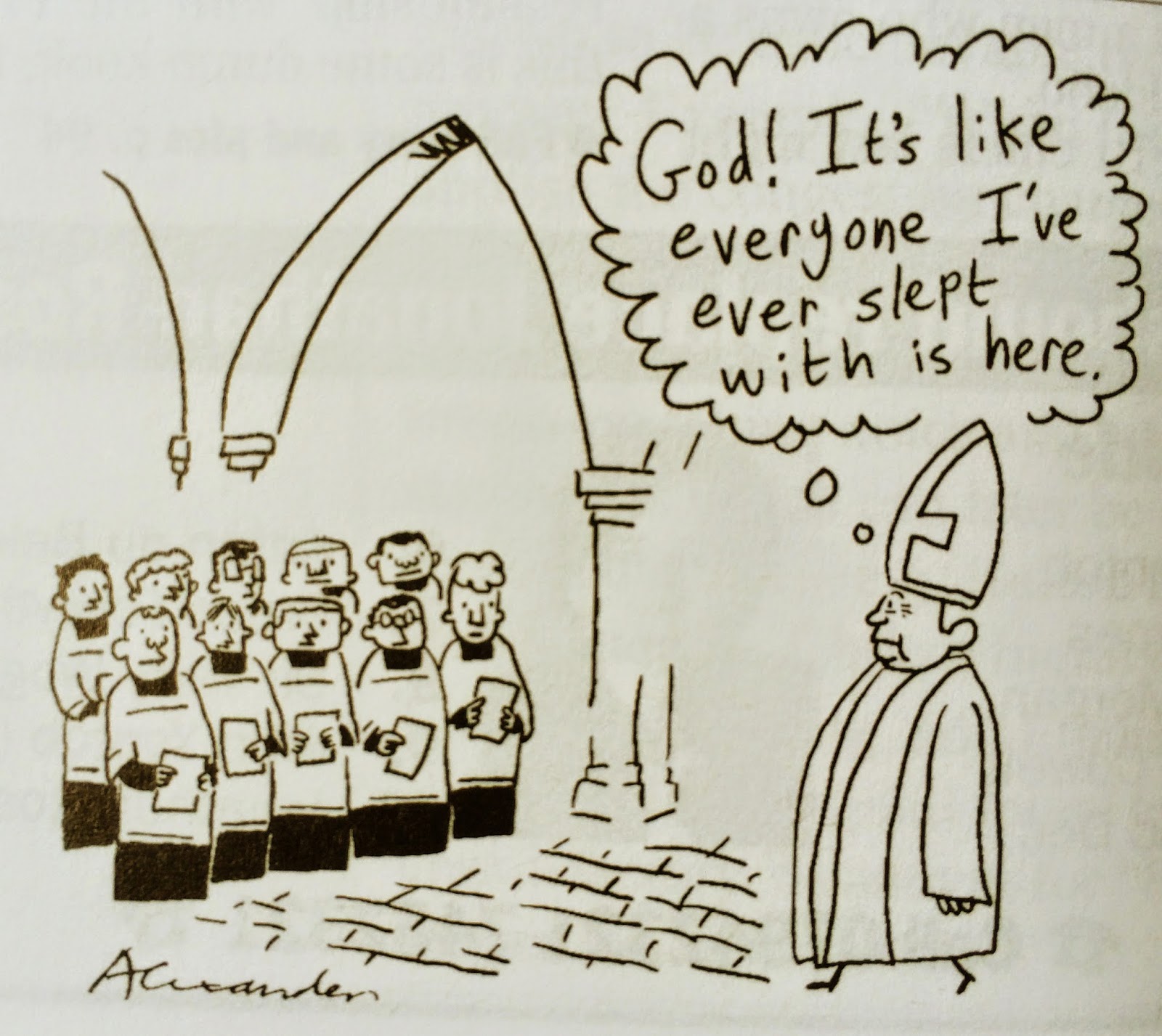

The cartoon I reproduce here from Private Eye (first published in 2010) is grossly offensive. It represents, nevertheless, something true: the shamefulness of the Church, as seen from the outside. It is not accurate: it is, after all, a cartoon. What I want to say about it is that it should make us ashamed that such a joke could be made about the Church, with some degree of justification.

The cartoon I reproduce here from Private Eye (first published in 2010) is grossly offensive. It represents, nevertheless, something true: the shamefulness of the Church, as seen from the outside. It is not accurate: it is, after all, a cartoon. What I want to say about it is that it should make us ashamed that such a joke could be made about the Church, with some degree of justification.

The Duke, disguised as a friar, confronts the pregnant Juliet in Measure for Measure about her repentance for the sin which led to her condition:

'Tis meet so, daughter: but lest you do repent,

As that the sin hath brought you to this shame,

Which sorrow is always towards ourselves, not heaven,

Showing we would not spare heaven as we love it,

But as we stand in fear,--

She replies:

I do repent me, as it is an evil,

And take the shame with joy.

When we contemplate this shame, we should not feel sorry for ourselves - poor us, having to feel shame! - but embrace the shame as the correct response to an objective evil. The shame is a gift. It is the beginning, if we take it in the right way, of reparation.

And this is the second thing: reparation. We cannot repent on behalf of others, but we can make reparation on behalf of others. We must make reparation for crimes closely associated with the Church, such as those by Catholics, or crimes of sacrilege. We can also make reparation for the crimes of society as a whole.

This is something which too many Catholics have forgotten, but it is something which is of the utmost importance. Without the language and the practice of reparation we have nothing to say, and nothing to do, to deal with the horror of systematic crimes by Catholics, of which paedophilia is the most obvious recent example, or the overwhelming crimes of society, such as abortion. We must make reparation. Reparation, voluntary penance or other good works offered in acknowledgement of some sin, is a participation in the expiation of the sins of whole world by Christ. By participating in this way we apply that perfect expiation in the most urgent way to the most urgent matters of our day. Christ's sacrifice is not incomplete in itself, but it is incomplete as it applies to us and to our society, otherwise sin would be no more. It is that completeness of application which we can advance by our actions, just as it is the glory of God on earth, in men's hearts, not His infinite glory in heaven, which can be increased by our actions.

|

| High Mass for the Ember Saturday of Lent, Our Lady of Caversham |

We are right to give thanks, we are right to rejoice, but we also need to do penance and to make reparation. In my next post I shall say something about reparation and the liturgy.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Historic crimes: repentance and reparation, Part 1

|

| Top left: St Edmund Campion, top right St Ralph Sherwin; bottom left St John Payne; bottom right Bl John Ford All priests, tortured for information and executed on trumped up charges of treason under Elizabeth Tudor. Stained glass from St Edmund's College Ware. |

This week I can't do much if any blogging, so I shall be reposing this series of posts from September 2014.

--------------------------------------------

Further to my posts about 16th and 17th century Anglicanism and the Islamic militants of today, a similar argument has now been made in a mainstream publication, The Week, by its Senior Correspondent, Michael Brendan Dougherty. Dougherty's focus is on the policies which led up to, and responded to, the Irish Potato Famine of 1847: much closer to home than the Tudor persecutions. He makes an interesting point about local dissidents being used as a proxy for foreign enemies, a point related to something I have been saying about the problem of the Church being aligned too closely with the decadent West.

In this post, however, I want to explore another aspect of the problem. If we are to talk about the past, and the bad things which happened there, which may or may nor have parallels with the present, the question arises of the what attitude the modern successors of the evil-doers should have to it.

This problem is more acute for the Catholic Church than for most religious groups, for two reasons. One is that it is the oldest institution on earth, of which one can say: this man here is the lineal successor of that one from the distant past, with a recognisable institution around him. The English monarchy is not as old as the Catholic Church by nearly five centuries, on the most generous analysis, and I can't think of any other institution around today as old as that. Almost any event you care to mention in European history since about the third Century has the Catholic Church as a protagonist, and often she is the only one still around to shoulder any blame which might be going.

The other reason is that the Catholic Church does not repudiate her past teaching. As I remarked in my posts on Anglicanism, Anglicanism today is completely different from the Anglicanism of the 16th century. Modern Anglicans can, if they like, simply say that Cranmer (for example) was wrong. Why not?

Catholics can't as easily say that important figures from the Catholic past were wrong, because of the way their writings and actions are bound up with the irreformable teaching of the Church. Sometimes, of course, they were wrong - there have been bad priests, bishops, popes, and Catholic kings and emperors - but the disentangling of personal and doctrinal, fallible and infallible, human and divine, in the Church can be a complicated business, and it is understandable if victims of criminal Catholics become a bit impatient with the argument.

To keep things simple, let's consider phenomena with which the Catholic Church can be said to be involved, at least at a human level, which are reasonably recent and unequivocally bad. There are two obvious ones: antisemitism and paedophilia.

Fr Alexander Lucie-Smith has recently written:

Historically, there have been Catholic anti-Semites. We need to repent for this, and we have done so, not least through the words of St John Paul II.

I think this is not quite right. Repenting for the sins of others is a bit too easy - or would be, if it were not impossible. St John Paul II didn't repent, he didn't need to, but he apologised. What exactly that meant remains controversial. I would suggest that it implies, for starters, a willingness to undertake two things which we may, in particular cases, need to do.

First, as the institutional successors of criminals, we may need to compensate the victims. The English Provincial of the Rosminians, Fr David Myers, once protested that to pay compensation to victims of historic child abuse would take money away from his order's current charitable activities: it would punish the innocent of today. Well that's too bad. If an institution seeks to benefit from its past, the buildings and institutions and endowments and so on, it must accept responsibility for the bad things as well.

Second, we must show that we do not endorse the ideological underpinnings of past crimes. Which is to say, whatever arguments were advanced for anti-Semitic attitudes, or, in the case of paedophilia, for the strange combination of sexual antinomianism and clericalism which permitted and covered up the crimes, are not arguments whose criminal conclusions we accept, and are not arguments which are valid in relation to the authentic magisterium. I have in fact written in this vein on both subjects: the errors involved in the attempted justification, from a Catholic perspective, of an attitude of hostility to Jews, and on the theological distortions at the root of the blind eyes which were turned to peadophilia, and also here and here.

There is something else we need to do, which is on a more spiritual level, and may also be part of what St John Paul meant by his apologies, and what Fr Lucie-Smith means by 'repentance'. I shall talk about it in the next post: it is spiritual reparation.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Youth Conference for Catholic Medics: 29th September, London

The Catholic Medical Association invites all young (18-35yrs) Catholics in healthcare (doctors, nurses, medical students, nursing students, pharmacists etc) to the Third Annual CMA Youth Conference. Speakers and a panel will explore the meaning of the culture of life in relation to healthcare and how to live by that culture in our professional and personal lives.

Entry is by donation (suggested donation: £5, payable at the door). Please be generous in order to enable the continued work of the Catholic Medical Association's Committee for the New Evangelisation (CMANE). The CMANE supports young Catholics in healthcare.

Register at: buildingacultureoflife.

Further information about the talks:

What is the Culture of Life? – Fr Stephen Boyle

An overview of the prophetic teaching of Humanae Vitae. How does the culture of the modern secular world reject the Church and it's message of the Good News? How does that culture affect bioethical issues such as abortion, euthansia, the family etc.?

Bringing the Culture of Life to young Catholics in Healthcare - Dr Adrian Treloar

What is it to be a Catholic in healthcare? How do we live out our lives according to this culture of life? What sort of clinical situations might you be faced with which oppose the culture of life?

Panel Discussion with Catholic clinicians, nurses and midwives

A chance to explore some of these clinical scenarios further and how to respond to them in a polite and professional manner.

Work as Prayer – Fr Gerard Mary OFM Conv.

Fr Gerard will talk about the importance of a strong prayer life for young Catholics in healthcare, and then briefly about the role of Walsingham in the re-dedication of England to Mary and the work of the New Evangelisation.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Traditional spirituality is part of the solution to the abuse crisis, not part of the problem

|

| Fr Richard Bailey of the Manchester Oratory celebrates Mass for the St Catherine's Trust Summer School in St Winifride's, Holywell, in Wales |

As regular readers know, I have from time to time addressed the claim that 'traditional' spirituality and attitudes are part of the cause of clerical abuse. This idea, more often assumed than stated clearly, is part of the reason why the liberal mainstream media has been more comfortable reporting abuse, and failures to deal with abuse, by bishops and indeed Popes regarded as conservative. To make a fuss over Archbishop Rembert Weakland, whose homosexual affairs were as notorious as his dissent from the teaching of the Church and his wreckovation of his Cathedral, ran against the narrative. It seems to have left editors scratching their heads and wondering how to play the story. They are still doing so today with stories about Cardinal McCarrick.

The power of the 'media narrative' is extraordinary, and needs explaining. Here's an article which says the American media is so inward-looking they suffer from group-think. But the attitude which this narrative reflects is also found in the Church.

I want to say something about the association of ideas at work here, making use of things I have already written on this blog.

First a disclaimer: whatever I say below should not be taken as a denial that immoral behaviour and various kinds of abuse can happen in the context of the traditional liturgy and spirituality. Abusive behaviour is not officially sanctioned by any strand of opinion in the Church, so an abuser is always going to have some strange, self-justifying, ideas. Such ideas can and have been put forward in what would otherwise be a traditionalist milieu, just as they have in what would otherwise be a theologically liberal milieu. The case of Carlos Urrutigoity is Exhibit A here; there are other cases. I'm not going to wallow in the details, but neither am I going to brush this under the carpet.

Back to this association of traditional attitudes and abuse. It works as follows. Traditional morality is about suppressing, sublimating, and channelling desires (/appetites /passions), so that desires, which are not under the direct control of reason, can be brought under the indirect control of reason. The principle applies to all desires, but the most powerful of them are sexual. Aristotle gave a philosophical account of the process of the training of the moral agent through the formation of habits, which has been adopted by the Catholic tradition, but the basic idea is found in all traditional societies and the Bible, even if the details about when it is permissible to act on a desire for this or that object has varied. Against this, we have the thought, not original to but articulated most clearly by Freud, that psychological problems, especially those involving sexuality, are the result of sexual repression. I will call this 'the Freudian principle'. On this view, suppressing, sublimating and channelling powerful desires leads to uncontrollable outbursts and harmful behaviour. They need, instead, an outlet.

A neat illustration of the clash between the two approaches is the long-running debate about whether sex-offenders in prison should be supplied with pornography. To anyone with a traditional or Aristotelian way of thinking, the proposal appears utterly insane. To those influenced by the Freudian principle, it is obvious, humane, and necessary. Oh, and the latter has zero empirical support. It is pure dogma.

The Freudian principle also influences the post-war theory of 'the rigid personality', whose patterns of thought and terms of art are echoed, as I have argued, in the words of Pope Francis, and of many of his generation. Its influence was great in the 1960s and 1970s, just when this generation was most open to influence, and when the Church's defences were very low. (See this thread.) The theory was developed to explain the rise of Nazism by Theodore Adorno, who connected what he called 'authoritarianism' with conventional morality. Adorno and his followers saw Nazism as a refuge for people with weak egos, who could only cope with the world in the context of strict rules, slavish obedience to which promised the approval of their colleagues and superiors. Since these rules are repressive, the scene is set for brutality. This is admittedly the simplified, cartoon-version of the theory, but it is in this boiled-down form that we find it being repeated by seminary rectors and the like thirty years later. A concern to keep old-fashioned rules is an indication of psychological weakness, or worse.

The genuine insight in Adorno's theory is that conformists can be attracted to rule-governed, hierarchical organisations, and that this is a problem because (to simplify) conformists are not good in a crisis. If you take away the Freudian principle, the assumption that traditional restrictions on sexuality and other things are psychologically damaging in themselves, we are left with the reality that conformism can manifest itself in relation to any set of rules. The extreme end of the psychology of conformism is exemplified by cults, which commonly have totally novel rules of behaviour. It can very easily be exemplified in Communist systems where conventional morality is largely rejected, or for that matter in institutions characterised by liberal Catholic theology.

This is important, because it is undeniable that there was a lot of conformism in the Church in the early and mid-20th century, and a central part of the Traditionalist understanding of history is that conformist bishops and priests were incapable of responding appropriately to the crisis which followed the Second Vatican Council. The Catholics of today who are trying to recover some of the spirituality and moral outlook of the pre-conciliar era are not conformists: they are rebelling against a brutally imposed and rigidly enforced non-traditional set of rules, in the secular sphere and in most institutions of the Church. The conformism of the last generation before the Council holds no attraction for them, even if what that generation was were conforming to, such as Thomism or the Divine Office, does pique their interest. Thomism and the Divine Office obviously have no internal connection with conformism, in the sense in play here. They originated in an era completely different from the stifling atmosphere of the 1950s.

If you find that last paragraph incomprehensible, try to keep in mind these points.

1) It is possible to be a conformist in relation to a wide range of systems of rules, not only rules which are chosen to oppress, but perfectly reasonable rules, and even rules designed to liberate. Conformism will lead to an unhealthy attitude to the rules and an incapacity to use their underlying principles to deal with unexpected situations.

2) Only if you accept the Freudian principle (that keeping your hands off your spouse's best friend is, to quote that liberating, artsy, film Two Girls and a Guy, a form of self-mutilation), will you assume that there is any intrinsic connection between a moral system which seeks to channel sexual impulses in a way which is not utterly destructive of society, on the one hand, and 'rigidity', oppression, abuse, and violence, on the other.

The oppression and abuse which took place in dioceses, religious communities, and of course in non-Catholic contexts, from the early 20th century onwards, was crucially facilitated by conformism. I don't think anyone would dispute that. What is equally clear is that the kind of conformism necessary for the cover-up culture did not disappear with the Council (in the Church) or the Sexual Revolution (in the World), but carried on, and indeed is clearly alive and well to this day. In a crisis, conformists cling to procedures and denounce whistle-blowers. They value the opinions of their peers and superiors more highly than the welfare of their subordinates. They back away from difficult tasks and gravitate towards easy or impossible ones. Yes, all the signs are there.

We can use this dismal history to test the truth of the Freudian principle itself. Is abuse more likely in the context of a moral theory in which sexual urges are repressed? As far as the records go (they are of limited value in my view), we can trace Catholic clergy abuse cases from the early 20th century to a peak at the end of the 1970s, and a decline thereafter. This is precisely the era in which the 'repressive' model was replaced by a Freudian model of morality in the Church: not in official teachings, but in seminary teaching, guidance for priests, and the attitude of most, if not all, bishops.

The triumph of the Freudian principle in the Church has been illustrated in detail by the book After Ascetism by the (American) Linacre Centre (2006). In 1958 the Catholic priest and psychiatrist T.V. Moore published Heroic Sanctity and Insanity, the last of his books. It describes the conflict between Freudianism, and aspects of other fashionable theories, with the Church's teaching and practice. This is obvious, right? In the last analysis the Freudian principle is not compatible with clerical celibacy. Moore makes the case that ascetic practices and prayer are, contrary to those theories, psychologically helpful. However, a decade later, when the US Catholic bishops commissioned a report into the psychological health of the priesthood, they chose a researcher completely in hock to the Freudian principle, Eugene Kennedy. The Kennedy report, which came out in 1972, did not even ask about priests' spiritual lives and practices (After Asceticism, p.49). Nor did it gather any data on priests' sexual orientation or their sexual activities. In short, it is impossible to look in its findings for correlations between anything thrown up by the interviews and actual outcomes. Kennedey's own conclusion was that priests should be told to chill out.

There is little indication that American priests would exercise freedom in any impulsive or destructive way. (After Asceticism p52)

This, of course, was at the very moment of the acceleration of the abuse pandemic.

Kennedy's approach is found again and again in later officially approved and officially influential studies. The famous 2004 John Jay report, for example, which perforce had to survey cases of abuse, presented no data on spiritual practice or lack thereof, and presented its data on cases of abuse in such a way that no correlations could be investigated between abuse and dioceses or seminaries. The dogmatic, fingers-in-the-ears determination of these researchers to consider only 'repression' as a possible cause of abuse served as no impediment to their being retained as advisers to the bishops in the lead up to, during, and after, the sex abuse crisis of 2002. Again, it is to institutions wedded to the same Freudian principle that clerical abusers have been sent by their bishops to help them recover.

If ever a hypothesis has been tested to destruction, it is surely this one: that spiritual self-discipline, asceticism, and traditional moral standards made abuse more likely. Might it be time to reconsider the wisdom of the centuries, in light, for example, of modern research confirming what all the spiritual masters said, that fasting reduces sexual appetites? Perhaps they weren't such fools after all. Might it not be time to bring back into focus spiritual, as well as purely natural, factors in the psychological health of clergy and laity? In short, might it not be opportune to reconsider traditional spirituality and practice?

Traditional spirituality is not magic. The process by which desires not under the direct control of reason can be brought under its indirect control, even with the help of God's grace, takes time, and even those seriously addressing themselves to this in their lives do not always complete the process before they die. Furthermore, as we are discovering with the box-ticking approach to child protection, any disciplinary system can be subverted by moral cowardice and conformism. However, that observation should not stop us preferring a better disciplinary system to a worse one.

|

| St Dunstan bests the Devil |

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Are things simply going to get gradually better? Or should we hang some bishops?

I was a little startled to read over the last 24 hours two calls for bishops to be hanged. One was from Matthew Walther, writing for the non-Catholic, mainstream magazine The Week. Walther is no anti-clerical fanatic, but a faithful Catholic. He is writing with a touch of hyperbole, perhaps, but he is making a serious point.

McCarrick obviously should not have been elevated to the cardinalate in 2001. He should not have been made archbishop of Washington. He should not have been simply "removed from public ministry" a month ago, but defrocked. In the time of St. Pius V, a cleric found guilty by an ecclesiastical tribunal of McCarrick's crimes would have been publicly executed by the secular authorities.

That would have been fitting. Indeed, I cannot really aspire to some kind of quasi-journalistic neutrality here. I believe that anyone who abuses a child should be put to death, priest or layman, man or woman. I hate child abusers with a perfect hatred, one that rests uneasily in my heart with the imperative of forgiveness enjoined by Our Lord.

This is unfortunately no longer even a remote possibility in the United States, thanks to the Supreme Court's decision in Kennedy v. Louisiana. At the very least, however, McCarrick should be prosecuted aggressively to the furthest extent possible by the laws of the various states in which his alleged crimes were committed.

The other call for the hanging of bishops was in relation to Anglican bishops. You know, those harmless, bumbling, decorative appendages of Britain's delightfully antiquated constitution. The writer, the Anglican cleric Jules Gomes, is a provocateur, but what he's saying is not simply a joke.

Lord Acton argues that those seated on thrones of power should not escape justice. ‘You would spare these criminals, for some mysterious reason,’ he tells Bishop Creighton. ‘I would hang them, higher than Haman, for reasons of quite obvious justice; still more, still higher, for the sake of historical science.’

So far, the IICSA is exposing the corruption of absolute power in the Church of England. Lamentably, we can’t hang corrupt bishops. Neither can we strangle the last bishop with the entrails of the last politician. We can do far more and pray Mary’s Magnificat that God will ‘pull down the mighty from their thrones and exalt those of humble estate’.

Those of my readers who are momentarily forgetful can refresh their memory of the edifying end of Haman in the Book of Esther here. The point is that he was hanged on a very high scaffold indeed: one he had intended for the righteous Mordecai.

The news about Cardinal McCarrick has sent the Catholic commentariate into a kind of furious despair, and as Gomes reminds us, similar things are unfolding in the Anglican world. This parallels the feelings of many in the secular sphere over the 'MeToo' scandals. It is because it so long, now, since the abuse scandal broke, and since those in charge agreed to strict new principles, and told us all that things would be different from now on. It comes as no surprise to those watching things carefully that things have not, really, changed very much, but it is still indescribably frustrating.

What is clear now is that the earlier media circus about clerical sex-abuse, which focused on people like Cardinal Groër of Vienna, Cardinal Law in Boston, and Cardinal O'Brien in Edinburgh, was highly selective. As Philip Lawler pointed out long ago, Law was convicted of covering up clerical abuse, a crime undoubtedly committed by many other American bishops. Yet no other US bishop was charged with this. (A few were charged with being abusers themselves.) O'Brien and Groër were brought down for relationships with seminarians. Yet it turned out that Bishop Conry's adulterous affairs were an open secret for decades, and Cardinal McCarrick and Archbishop Weakland had been semi-publicly paying off former lovers/ victims using Church funds.

Why were those three, and a few others, targeted? Media people sometimes say that they don't like to expose 'consensual' sexual relationships. But there is no substantial differences, as far as consent is concerned, between O'Brien and Groër, on the one hand, and McCarrick and Weakland, on the other. No: the difference is that the people brought down were regarded as theologically conservative. O'Brien had a mixed theological record but the occasion for his downfall was his opposition to same-sex marriage.

The media's preference for exposing conservative politicians and other public figures is equally easy to illustrate. (Compare the treatment of Trump's bragging and Bill Clinton's interns.)

I wonder if this pattern reassured some of the remaining abusers that they were safe if they played up their liberal credentials. But things have taken on a momentum of their own, one which is harder for the 'legacy' media to control. The abuse crisis has been unimaginably painful for the Catholic laity, who are far more even-handed in their condemnations than the mainstream media, and the weight of testimony and other evidence was bound to catch up with other prolific abusers in the end. To be reassured that everything is going to be different now, and then see a series of scandals coming out all over again, is breaking the laity's patience. It is particularly galling to recall that McCarrick was personally involved in the response to the abuse crisis. And that the other bishops saying the warm words were surely perfectly well aware of the irony of the situation.

What it means, alas, is that it is not just the abusers themselves who cannot be trusted. It is the great majority of the US bishops, bishops who did nothing, said nothing, went along with and supported the official response and the business as usual charade. (A notable exception was Bishop Bruskewitz of Lincoln, Nebraska, who refused to comply with the 'Dallas Charter', the absurdly misconceived, and as we now know, deeply hypocritical, official response to the crisis.)

Bishop Thomas Tobin of Providence, Rhode Island, regarded as a conservative, learnt this the hard way on Twitter. He tweeted a few days ago:

Despite the egregious offenses of a few, and despite the faults and sins we all have, I’m very proud of my brother bishops and I admire and applaud the great work they do everyday for Christ and His Church.

I can't screen-shot it because he has now deleted his entire account. He said that Twitter was distracting him from his spiritual life and was an occasion of sin for others. What actually happened, as you can still see by searching for his old handle @bishoptjt and from this article, is that his sentiment was greeted by an overwhelming number of very polite but outraged responses from Catholics. I myself pointed out that is it not the offences of the few which are the problem, now, but the silence and complicity of the many.

I feel a little sorry for Bishop Tobin, because this kind of establishment boiler-plate has gone done perfectly well for decades. It is a little curtsey from a bishop with a conservative reputation to the dominant liberals of his conference. I says 'It's ok, I'm not going to rock the boat'. And it suggests, without quite saying it, that not rocking the boat is what Jesus would have wanted, and that lay conservative Catholics shouldn't rock the boat either.

This is not the moment for such sentiments, however, and it says a lot about the force of his ingrained habits of mind that Tobin thought it would work.

One should be wary of attributing to 'the bishops' the sins of their predecessors, but it remains true that no Catholic bishop in the United States has broken ranks to condemn the system of mutual back-scratching and cover-up which has allowed prolific abusers not only to exist but to flourish. Not all the bishops of the United States are themselves engaged in the back-scratching and covering up, but they all know about it. I'm sorry, but yes they all know about it. How stupid and ill-informed would they like us to think they are? They have seen it with their own eyes. And yet they say nothing.

Is the same true in Britain? I do not know. The fact that two of our biggest scandals have involved heterosexual adultery - Bishop Conry of Arundel and Brighton and Bishop Roddy Wright of Argyle and the Isles - may suggest that there is a slightly different pattern here. On the other hand, the Cardinal O'Brien scandal suggests a systematic problem: he was Archbishop of Edinburgh 28 years, and since he was helping himself to seminarians over that time the damage he must have done is incalculable. It is possible that something like that will revealed about an English bishop; we will have to see. I don't want to condemn anyone in advance of the evidence.

The loss of trust, however, cannot be contained: if it is lost in America, it will have its effect all over the world. The attitude of conservatives in the hierarchy, and many conservative laity, has been that if they quietly do their work they can do good, and that because of (delete as appropriate) the good policies of Pope John Paul II / Pope Benedict XVI / the new generation of Bishops / young priests, things will gradually improve. That was always an optimistic assessment, and it is now clear that it is false. As I have written before, the evangelisation of our society is impossible without the restoration of the moral authority of the bishops. And that is not going to happen now without some kind of cathartic crisis. There must be a clear-out, and there must be a clear stand taken by the remaining, or new, bishops.

It is quite simple, actually. As Cardinal O'Brien demonstrated, it is impossible for bishops who are personally morally compromised to take a clear stand on the crucial issues of the day, because they will be destroyed by the people with dirt on them, with the help of a gleeful secular media. All that needs to happen, therefore, is for bishops to take such a stand. Those who cannot? Never mind talk of hanging: I'll settle for a quiet resignation.

Update: see Michael Brenden Dougherty on the 'biological solution'.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Bishop Schneider on the LMS's liturgical music

|

| Bishop Schneider in St Mary Moorfields, London |

The polyphony of this Mass, sensitively chosen for the celebration and exemplifying the great breadth of the English choral repertoire, was beautifully sung by Cantus Magnus under the direction of Matthew Schellhorn: his generous artistic contributions in the field of Sacred Music are of true value in upholding the dignity of the Sacred Liturgy.

Both the artistry of these works and the sensitivity of their execution clearly evidenced a deep love of the Sacred Liturgy – characteristics intrinsic to the English Catholic music tradition.

Thanks to the support of the Latin Mass Society under its Chairman, Dr Joseph Shaw, the authentic Catholic musical tradition of England, Our Lady’s Dowry, is fostered and kept alive to the benefit of the whole Church.

This rejuvenation of the Church through Sacred Music is greatly encouraging. In the words of His Holiness Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI [then Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, speaking at VIII International Church Music Congress in Rome, 17 November 1985]: ‘True liturgy, the liturgy of the communion of saints, gives man once again his completeness. […] By “lifting up the heart;” true liturgy allows the buried song to resound in man once again. Indeed, we could now actually say that true liturgy can be recognized by the fact that it liberates from everyday activity and restores to us both the depths and the heights: silence and singing. True liturgy is recognizable because it is cosmic and not limited to a group. True liturgy sings with the angels, and true liturgy is silent with the expectant depths of the universe. And thus true liturgy redeems the earth.’

His Excellency Athanasius Schneider O.R.C.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Fr Mark Morris sacked as Chaplain of Glasgow Caledonian University over prayers of reparation for Pride event

|

| Fr Morris, centre, at the Latin Mass Society Priest Training Conference at Prior Park, in 2015. |

From Church Militant:

Read the story there.

The story is both outrageous and predictable. Naturally the University authorities have no interest in the integrity of the Catholic faith or the freedom of its adherents to act on it. They have no interest in academic, aesthetic, or historical integrity either. Their only interest is in not falling out with the latest student politically correct demand, as it was over the issue of Rudyard Kipling's poem on display in Manchester University, or the former Provost of Oriel over the statue of Cecil Rhodes. As far as University administrators are concerned, students are customers, and if students wanted to be taught nothing but the collected poems of Minnie Mouse and have rainbow flags adorning every tower, they would do their best to arrange it.

I think, nonetheless, that prayers of reparation for such evils are not only morally necessary but a good way of manifesting the Faith. Anything Catholics say or do about homosexuality is going to be interpreted as homophobia, but prayers of reparation locate the issue firmly at the level of personal sin and scandal. It is insofar as Pride events are celebrations of a lifestyle characterised by sin - insofar as they are, in fact, propaganda exercises for sin - that they are problematic. And it is precisely this aspect of them that those objecting to Fr Morris' prayers are objecting to.

There will be a votive Mass of Our Lady of Guadalupe in reparation for abortion in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford, at 6pm on Wednesday 28th November.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.