Chairman's Blog

Michael Davis attacks home-schoolers

|

| The quiz at the end of the St Catherine's Trust annual Summer School, attended by about 50-50 home-educated and school-educated children. Details of this year's here. |

Cross-posted from Rorate Caeli.

A while ago the Catholic Herald journalist Michael Davis thought he'd do a good turn to the Traditional Catholic movement (with which he apparently identifies) by describing us as hateful bigots and antisemites. Now he's decided to do a similar favour to homeschoolers.

It works like this. First, Davis starts the article with a reference to the staggering success of homeschoolers: it seems that they are providing 10% of vocations to the priesthood in the USA, a proportion vastly in excess of their numbers.

Second, Davis lists all the tired old criticisms of homseschooling. Homeschooling is against the teaching of the Church; the children aren't 'socialised'; the parents are 'helicopter parents' who 'seal off their children in a bubble'; even the apparent good of the vocations is undermined by the snarky suggestion that the vocations aren't genuine and the priests won't be good pastors.

Step three is to hold up his hands and say: Oh well, maybe these problems can be avoided by some homseschoolers. Citing one particular group, he says vocations coming from it 'won’t be stereotypically paranoid, socially awkward homeschooled kids': unlike all the other homeschooled children, right?

No doubt he expects us all to congratulate him on what a balanced article he has produced.

The problem is that, just as in the 'oh perhaps not all traditional Catholics are hateful bigots' article, he has reiterated and reinforced an extremely damaging negative stereotype which needs confronting and assessing. Is it true? Because obviously, if the stereotype isn't true, then a balanced assessment would use it even as one side of the see-saw.

The claim that home education is against the teaching of the Church, perhaps with an exception for 'crisis' circumstances, is obviously insane, since, first, the Church has always taught that parents are the 'primary and principal educators' ('primi et praecipui ...educatores': Gravissimum educationis 3, Vatican II) of their children; and, second, the existence of schools available even to the majority of the population, let alone all of it, is not only historically contingent but historically rare. It is rather more reasonable to say that good Catholic schools, where they exist, can offer educational, social and cultural opportunities homeschoolers will generally find difficult to arrange, and that parents' choice of educational options will take this into account. But that doesn't have quite the same ring to it, does it?

Are children not as well 'socialised' with home education than in standard schools? Is there any actual, you know, evidence out there? Well, here's an article in The Economist, hardly a hippy or traddy publication, which notes:

Nor, on the evidence of Mr Murphy’s book, are they socially backward: most seem confident, assured and well-adjusted. They also have fewer behavioural problems. But one study did find higher attrition rates when they enter the armed forces.

If Davis prefers to keep things at the level of anecdote, I would suggest he spends some time with children from ordinary schools and home-schooled children of equivalent ages. If he has remotely representative children to talk to, he will discover for himself the often-repeated truth that the latter exhibit greater social skills, self-confidence, and intellectual curiosity. In a good many cases, in fact, children are taken out of school and put into a homeschooling routine because the vaunted 'socialisation' of ordinary schools is threatening to do them permanent psychological damage. If Davis has not, in fact, met people who have been badly harmed by the 'socialisation' of standard schools, he needs to get out more.

So, is homeschooling 'the ultimate form of helicopter parenting'? At this point I feel like banging my head on the table. Has he actually talked to any? Home educators don't all have the same educational philosophy, any more than schools do, but it is the nature of homeschooling that teachers can't arrange 24-hr contact time, because the teachers - mostly parents - have other things to do, including other children to teach. This means that children are challenged to work on their own from an early age, and are freer pursue their own interests. Furthermore (and here's a point connected with the question of socialisation), homsechooled children will spend more time in different groups doing things like sports: unlike a parochial school, it won't be the same 30 class-mates in the playground, on the hockey field, and in the chemistry lab. What parents can do, of course, is to establish to their satisfaction that the things their children are doing, and the people they are doing them with, are ok, and intervene if they are not.

Helicopter parenting, if the phrase means anything, is a reaction to the problems of children swapping internet porn, bullying, and inadequate classroom teaching, and it is a reaction which does not work. No amount of ringing up the headmaster and attending parents' meetings can effectively deal with those issues, as we have all heard (those of us who haven't stuck our fingers in our ears) from countless despairing parents. Homeschoolers don't need to 'helicopter' their children because they can ensure that they are safe and are being educated.

Finally, do homeschoolers 'seal their children off' in a 'bubble'? Here's a funny thing. That is what schools are supposed to do. When you send your children off to school, the idea - if there is any idea at all - is that this completely artificial, enormously complicated, and hideously expensive institution constitutes a special environment, contrived after deep thought and long experience, to be uniquely conducive to education and socialisation.

As a matter of fact I don't think schools have ever been very good at socialisation: just read a few school reminiscences, such as the relevant passages of Betchman's Summoned by Bells or Lewis' Surprised by Joy, and the glory days of the English Public School quickly lose their charm. Today, with social-media bullying and the normalisation of playground rape, together with the almost total collapse of educational standards, the majority of schools in the developed world are a uniquely poor environment for both purposes. Like Anthony Esolen, I really wonder if children would be better off running around in the woods on their own. However, that's not the only alternative. Home educating parents set to work to create some kind of educational and socialising environment, and the results show that they they do so with a degree of success, even while leaving their children a lot more time to run around in the woods than children in schools have.

The claim that home educated children who discern vocations make bad priests is, I think, not worthy of a response. It is a disgusting, though apparently thoughtless, slur on hundreds of priests Davis has not met, and to those with the responsibility for forming them. Davis owes them an apology.

Davis does not appear to be interested in thinking seriously about the merits of home education. Perhaps that would be too much effort. Instead he just recycles negative prejudices on the subject while simultaneously admitting that the results don't seem too bad.

If this is what the Catholic press is about today, then it is about as much use as the Catholic educational system.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Counting our blessings: 10 years of Summorum Pontificum in England and Wales

|

| Bishop Schneider in London |

Last summer, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Summorum Pontificum, I was asked for illustratative statistics by Paix Liturgique. This is what I came up with, from the Latin Mass Society's records:

Locations with 'every Sunday' Masses (excluding Saturday evening Masses)

2007: 20

2012: 34

2017: 40

Christmas Masses (including Midnight, Dawn, and Day Masses)

2006: 10

2012: 44

2016: 71

I thought of these numbers when my attention was drawn to a post on a somewhat obscure blog which claims, without giving a great deal of even anecdotal evidence, that the Traditional Mass is 'stagnating' in England and Wales.

Another truth about England and Wales is that it is not Singapore: we don't all live in one high-density city. The spread of the Traditional Mass in England and Wales is a matter of getting it onto the parish schedules of more and more churches around the country, so that people can actually get to it. At this point people usually tell me that the Real Trads in the USA think nothing of 4-hour round trips to get to the EF on a Sunday, unlike the feeble people we call Trads here, but I would make two observations. The first is the cost of motor-fuel relative to average incomes in the two places. The second is that as a matter of fact there are a good number of Traditional Catholics who do go to extraordinary lengths to attend the EF, but that is about holding on to what you already know, not trying out something new which you might not like.

Getting the Traditional Mass into a new church, as a regular Sunday fixture, is an extraordinarily difficult thing to do in England and Wales. Our churches are heavily used and our priests are fully committed. Only in quite unusual situations can a time-slot and a priest both be made available. And so, yes, in the five years from 2012 to 2017, progress on this measure was of only 6 churches. Not much more than one a year.

As the squeeze on the number of clergy serving our churches tightens, the attempt to keep up all the existing Masses has made more and more demands on priests' time. One reaction by the bishops has been to try to protect their priests from impossible demands by stopping them creating new Masses, and trying to reduce the numbers of Masses in parishes - it's not as if they are all full - as well as by closing parishes. Drastic changes occasioned by parish mergers can occasionally make new EF Mass times possible, but naturally that is a very slow business.

However, we are winning at a more fundamental level, and this fundamental victory will in time be reflected in the number of Masses. What I mean is in the attitude of bishops and priests, particularly the influential senior clergy, to the Traditional Mass. Ten years ago, and before that, there was a great deal of hostility. While some still cling to that, for the most part this has melted away. It has done so partly as a result of generational change, but also because as the EF has become more widespread and normalised, everyone has been able to see that it, and the priests who say it and the people who attend it, are not freaks or monsters, but faithful Catholics.

Not only is the hostility disappearing, but the number of priests able and wanting to celebrate the Traditional Mass grows with every year that passes. The younger seminarians are not all keen on it, but if 50% of the brighter ones are, things are going to look very different in 20 years' time. And then there is the extraordinary number of vocations to the Traditional Institutes, notably to the Fraternity of St Peter, which have come from England and Wales.

Another issue to bear in mind is that, from the point of view of liturgical renewal, the Traditional Latin Mass has become, for practical purposes, the only show in town. The theoretical and practical impetus for 'Latin Novus Ordo' and varieties of 'Reform of the Reform', which have never spread beyond a tiny number of churches in this country, is played out. True, lots of people still go to the Latin NO in the Oxford and London Oratories, but no one is going to create new ones in new churches. It is a complete liturgical dead-end.

And here is something else. The experience of the last ten years has taught us that when the Traditional Mass is established in a new location, where there is little if any proven demand, it attracts a congregation. With the Traditional Institutes' new churches, this can be a congregation comparable or bigger than the typical prime-time congregation of nearby parish churches. Where we are talking about a church offereing both Forms, and if the Mass times provide a reasonably level playing-field, it can become the most popular Mass of the day. This has happened again and again, and reinforces my point that to spread the Traditional Mass what is needed, in the end, is for it to get into more churches.

It is frustrating to see so many priests who'd like to celebrate the EF on a Sunday in their churches not able to do so. But this pent-up supply is not going away: it is increasing. And when it is able to manifest itself in a new local Mass, it creates its own demand.

I'm optimistic about the future of the Traditional Mass in England and Wales, because of these longer-term trends. I have seen the transition from a generation of openly hostile senior priests and bishops to open-minded ones with other, urgent, issues uppermost in their minds. Knowing what the younger clergy are like, I forsee another transition among senior priests and bishops: from seeing the Traditional Mass as an eccentricity to be tolerated, or an opportunity for the off-loading of a crumbling historic church, to seeing it as a evangelical weapon to be deployed.

When that day comes, will we be ready?

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Young Catholic Adults: Douai Retreat 7-9th Sept

As always I'm delighted to advertise this long-running annual event.

--------------------------------

During the weekend of the 7-9 September 2018, Young Catholic Adults will be running a retreat at Douai Abbey, it will feature Fr. Lawrence Lew O.P., and Canon Poucin - the age range is 18-40.

The weekend will be full-board. YCA will be running the weekend with the Schola Gregoriana of Cambridge who will be holding Gregorian Chant workshops.

There will also be a Marian Procession, Rosaries, Sung Masses, Confession and socials. All Masses will be celebrated in the Extraordinary form.

Please note to guarantee your place this year Douai Abbey have requested that everyone books in 3 weeks before the start of the weekend i.e.17th Aug 2018.

More information: http://youngcatholicadults-latestnews.blogspot.co.uk/

To book:-https://bookwhen.com/youngcatholicadults-douai2018

To donate towards the costs of running the weekend please click here.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Can the Church forget doctrine?

| Drinking the mythical waters of forgetfulness in the underworld: Lethe. |

Reposted from October 2015

-----------------------------------------

At certain periods of history, one doctrine has been pushed to the fore either because it was needed to combat an issue of the day, because of its connection with a popular devotion, or because it was denied by heretics. Others have been pushed into the background. Being human, we can't focus on everything at once.

But there is something else, which is a doctrine disappearing from view because, although attacked by heretics, too many otherwise orthodox people are reluctant to defend and expound it. When these doctrines, and opinions which don't perhaps pertain to the Deposit of Faith but which are very authoritative, are mentioned, it can be a bit of a shock.

In researching the Position Paper on the Vulgate, I found a reference in a somewhat obscure official document published in 1994 to the ancient Greek translation of the Bible, the Septuagint, being made 'under divine inspiration'. I nearly fell off my chair. This is not, strictly, a teaching of the Church, but it is a pious opinion with considerable authority, taught particularly by the Greek Fathers of the Church. If it is taken seriously, then the policy of the Church since the 1940s to replace the ancient Latin translation of the Psalms, based on the Greek version, with new Latin and vernacular translations taken from the Hebrew, is fundamentally misguided.

Come back, 'valley of tears', valle lacrimarum: all is forgiven! You won't find that phrase in the reformed Office, the Novus Ordo Missal, or even the Knox translation of the Bible, when you look at Psalm 83.7 [84.6]. It is there in the Vulgate, and in the Greek, and in the ancient Gregorian chants: and, the Church is telling us, God wanted it there.

The policy of the Church, implemented through official organs of the Church like reforming commissions set up by Popes, Popes who then promulgated the results, runs counter to the belief of the Church. Looking more closely, this belief was even supported by Vatican II, but no matter: the policy trundled on, undisturbed.

This is an example which doesn't generate the heat of current debates about the indissolubly of marriage, and for this reason it can more easily help us, calmly, to consider what is and is not possible in the Church. There has been no official denial of the value of the Septuagint, though you'd be forgiven for thinking that such a denial was implied by the repeated efforts to strip its glosses on the Psalms out of the Church's spiritual life. One might call it a denial 'in practice', but clearly that isn't enough: we should not take our cue from policies, which go back a mere 70 years, especially when, every now and then, the contrary belief is reiterated in an official document. Looking at the tradition, over a much longer period, we see a very different policy, and it is that policy, the historic, traditional, policy, which represents the real practical outworking of the belief of the Church. It is this we can call the 'wisdom of the Church'.

Here's another example, with different characteristics. The Church has always taught that usury is wrong. The condemnation has been repeated in authoritative documents over many, many centuries, and the teaching derives from Scripture. We haven't, however, heard anything about this matter for a century or two, except from the odd popular writer. It could form the basis of an effective critique of capitalism, but the effort has never been made. The words 'usury' and 'usurious' occur once each in Leo XIII's Rerum Novarum (1891), and with no explanation. Things are so bad with this that the technical distinctions between different kinds of money-lending / investment upon which the doctrine is based are understood by almost no one. (There is an excellent explanation of it here.) Stray references to usury in magisterial documents never say that it is permissible after all; they just don't make use of the teaching. It has been forgotten, and of course that means it doesn't influence any practical initiatives involving finance the Church undertakes.

There are other examples. The doctrine of no salvation outside the Church would be one. Never mind the importance of understanding it correctly blah blah blah - all doctrines have to be understood correctly. But there is no understanding of this teaching, correct or not correct, which visibly makes any practical impact on the preaching or practice of the Church today, and it is many, many decades since it was even discussed in official documents. Many practical policies, arguably, actually run counter to this teaching. The same can be said of the teaching that husbands are the head of their households. Aside from Bishop Olmstead's recent Pastoral Letter, down the memory hole it goes. Again, while Original Sin still has vocal defenders, for much of the Church, and for the policies of official organs of the Church, it has vanished from sight. Practical life, notably in education, carries on as if it were not true.

These things are still the teaching of the Church; denial of them is still a serious matter which cuts us off from the Church. To repeat, forgetfulness, and official policies running counter to the teachings, do not imply that they aren't teachings any more. The teaching of the Church cannot contradict itself. What has been taught in Scripture and the Fathers and General Councils and the Ordinary Magisterium cannot be unsaid.

This doctrinal amnesia is not, I would say, a typical situation in the history of the Church. Emphasis and de-emphasis on teachings is typical; controversy is typical; sin is typical; but this is something else. It illustrates a dogmatic crisis which has been getting up steam over recent centuries, and of which we are the heirs. I would go so far as to say that it fulfils the implied prophecy in Our Lord's words.

For he that shall be ashamed of me, and of my words, in this adulterous and sinful generation: the Son of man also will be ashamed of him, when he shall come in the glory of his Father with the holy angels.

(Mark 8:38)

Could this forgetfulness encompass the Church's unchangeable teaching on the indissolubly of marriage?

Of course it could.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Loftus, farewell

|

| Fr Nicholas Schofield celebrating the EF in his church of Our Lady of Lourdes, Uxbridge, for the Chesterton Pilgrimage (an event promoting the Cause of GKC). |

I knew it had to happen one day: I would open my copy of the Catholic Times (I subscribe to all the Catholic weeklies), glance at Fr Francis Marsden's headline, turn the page to Fr Nicholas Schofield's chosen topic for the week and there, taking up most of the page under Francis Davis' regular slot, would be ... something other than Mgr Basil Loftus.

The day was today. Instead of Mgr Loftus' byline, there was a photograph of a young priest in a tree. A little odd, you might think, but the story was about sport.

I understand this is a permanent break, not a momentary pause, so it is something of significance.

Readers familiar with the names above - Fr Marsden, Fr Schofield, Francis Davis - will know that these are terrific, orthodox Catholic writers. Furthermore, Fr Schofield celebrates the Traditional Mass in his parish. Mgr Loftus actually used his column to attack Fr Marsden's column by name. And there are more good writers, in the Catholic Times. The permanent presence of Mgr Loftus cast a shadow over the paper which has now lifted. I wish the Catholic Herald would pluck up similar courage to cut its ties with regular writers who, like Loftus, seem to be left over from a former, darker, era.

The Catholic Times is shortly re-launching as a tabloid. I never thought I'd say this, but I think it deserves our support.

It so happens (perhaps not by chance) that Loftus' very last column was quite a nasty attack on those attached to the Traditional Mass, and I wrote a letter in response, something I've not felt motivated to do for a long time. It's not published this week, and I don't suppose it will be now, the moment has passed, but for the record I post it below. I'm not going to spend ages copying out chunks of his column to prove I've not misrepresented him; I just leave it here as a reminder of the problem Loftus represented.

Happy feast of the Sacred Heart to all my readers!

|

| O Jesus meek and humble of heart Make my heart like unto Thine. |

Sir,

Mgr Basil Loftus (1st June) writes that differences of liturgy imply differences of belief, and that resistance to change is ‘to fly in the face of the Holy Spirit.’

This may sometimes be the case, but he would do well to refresh his memory of the principles set out by the Second Vatican Council: ‘Even in the liturgy, the Church has no wish to impose a rigid uniformity’ (Sacrosanctum Concilium 37) and ‘let all… enjoy a proper freedom, … in their different liturgical rites... they will be giving ever better expression to the authentic catholicity and apostolicity of the Church’(Unitatis redintegratio 4) Pope St John Paul II declared that a ‘genuine plurality of forms’ is ‘the Church’s ideal’ (Orientale Lumen 2).

It is worth pondering the last point: that the universality, the Catholicity, of the Church is not weakened, but manifested and strengthened by liturgical pluralism, and, yes, by the fidelity to tradition common to the Eastern Churches and to those, in the West, who preserve the ‘treasure’ of the ancient Latin Mass.

Yours sincerely,

Joseph Shaw

Chairman, Latin Mass Society

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Masses of Reparation in Oxford and London

I'm happy to announce not only a Mass pro remissione peccatorum (for the remission of sins) in Oxford, but also one in London.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Anyone know the late John Arnell?

See the full story.

'Desperately' is not quite the word I'd have chosen, but we really would like to give any friends and acquaintances the chance to attend a Requiem for him in the most appropriate location possible, and it would be really nice to know something about him. We've tried some obvious avenues without success and now we've got the story into a local paper.

The bequest he has left us is not life-transforming for the LMS, but it is really, really nice and as the story says it is the largest single bequest we have ever received. This is particularly touching since Mr Arnell was not a man of great wealth: much of the money is simply the modest flat he owned and died in. Since there are no close relations, or friends acting as executors, it behoves us to ensure he is given a proper public send-off. (We have, of course, already organised Masses to be said for his soul.) It is upsetting that we weren't notified before the solicitors dealing with the case had body cremated... but we'll do what we can.

Anyone with informtion should email info@lms.org.uk

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Friday 15th June: Mass of Reparation for abortion, Oxford

|

| Mass for the Epiphany in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford |

There will be a Sung Mass in view of the Irish Referendum result:

Friday 15th June, 6pm

SS Gregory & Augustine's,

322 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 7NS

(click for a map)

The Mass Sung in the Extraordinary Form, with Gregorian Chant provided by the Schola Abelis of Oxford.

It will be the Votive Mass pro remissione peccatorum: for the remission of sins. The Mass texts acknowledge our sinfulness and our need for forgiveness, our dependence on God's mercy and our confidence in His goodness.

It will be celebrated by Fr John Saward, Priest-in-Charge of St Gregory's.

The church has a car park.

Friday 25th June: Mass of Reparation in Oxford

|

| Mass for the Epiphany in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford |

There will be a Sung Mass in view of the Irish Referendum result:

Friday 25th June, 6pm

SS Gregory & Augustine's,

322 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 7NS

(click for a map)

The Mass Sung in the Extraordinary Form, with Gregorian Chant provided by the Schola Abelis of Oxford.

It will be the Votive Mass pro remissione peccatorum: for the remission of sins. The Mass texts acknowledge our sinfulness and our need for forgiveness, our dependence on God's mercy and our confidence in His goodness.

It will be celebrated by Fr John Saward, Priest-in-Charge of St Gregory's.

The church has a car park.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

A pro-life appeal: Making the best use of our misfortunes

The best use we can make of a hideous, painful, and morally outrageous event like the Irish referendum result is repentance. Private repentance is always positive, but I would myself like to do something with a public manifestation, and to do this in collaboration with others, if anyone is interested.

It is a truism to say that penance is undervalued in the Church today. There is something amiss when one sees in the texts of the liturgy references to 'our fasts' and 'our mortifications' on days when no fasting or mortification is any longer required by the Church: this was the case on Saturday, the Ember Saturday of Pentecost. It is not just a matter of the dramatic cutting back on fast days since Vatican II, and not even the excision of references to sin and penance in the Novus Ordo, however: the problem goes further back, and penetrates the Church more deeply.

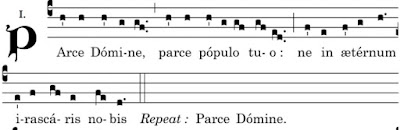

In any case, without changing the discipline of the Church (which I can't do) I would like to encourage priests to use the options which exist to express the Church's penitential imperative. For example, as the Latin Mass Society's Ordinary Prayers of the Traditional Mass notes, in Benediction the pre-Conciliar books permit and encourage the invocation 'Parce Domine' after the Collect 'Deus qui nobis' ('O God, who in this wonderful Sacrament...'), before the Benediction itself. You can say, three times:

Parce, Domine, parce populo tuo, et ne in aeternum irascaris nobis

or in English:

Spare, O Lord, spare thy people, and be not angry with them for ever.

Or sing it:

In addition to this, and for laity as well as priests, I have an idea, or the seed of one, for which I'd like to test wider support, of organising two (sung, traditional) public Masses a year in reparation for abortion and other manifestations of the culture of death.

One would be a Votive Mass of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which is celebrated in the USA on December 12th (and for that reason can be celebrated anywhere as a Votive Mass). Our Lady of Guadalupe, who is Patron of the Americas, has very appropriately been adopted by the Pro-Life movement as her miraculous image is of her during her pregnancy. I would ask for this to be celebrated on or close to her feast day.

The other would be a Votive Mass pro remissione peccatorum ('for the forgiveness of sins'), one of the Votive Masses found in the 1960 Missal. To give a flavour of the texts, the Gospel of this Mass is Luke 11:9-13, 'Ask and you shall receive'; the Gradual is Ps 78: 9-10: 'O Lord, forgive us our sins: Lest they should say among the Gentiles: Where is their God?' I would aim to have this celebrated at the other end of the year, in June: so, quite soon.

As the Representative of the Latin Mass Society in Oxford area, and the manager of a chant schola, it is a fairly simple matter for me to ask one of our many excellent priest supporters in the area to celebrate these Masses, to arrange chant accompaniment, and to advertise it locally. The cost would be minimal. However, if there is real support these Masses could be celebrated with more solemnity, with solemn ceremonies, with polyphony, in London, or in multiple locations.

Each celebration of Mass has infinite intrinsic value. This means that two Masses do not have greater value than one. The reason we have multiple Masses celebrated for an intention is because in addition to the intrinsic value of the Sacrifice of Calvary which is re-presented in the Mass, there is the 'extrinsic' value of a Mass, the value of its prayers and the prayers of those who attend it. It is in this sense that we say that a Mass celebrated with reverence is better than one with abuses; a Mass celebrated with greater solemnity is better, in this sense, than one with less; many Masses, involving many different people, are better than just one.

The principle reason for suggesting two Masses a year for this intention is to keep the cause in our minds, our hearts, and our prayers. I know lots of people do lots of things with this purpose: in England an outstanding example is the Rosary Crusade of Reparation in London, a procession from Westminster Cathedral to the London Oratory. I would like to add to these existing initiatives something which represents the specific contribution the Traditional movement, and the network represented by the Latin Mass Society, can make.

I'll make a start with this idea locally and quietly but if there is wider support I'll make more of it in the ways I noted. In particular, if Masses are to be said with professional choirs financial contributions will be needed, and if they are to be said in additional places, more people will have to take on the organising.

If you'd like to help email info@lms.org.uk with 'FAO Joseph Shaw' in the subject line.

Photos: Whit Saturday Mass celebrated in Holy Rood, Oxford, by Fr Daniel Lloyd, with Solemn ceremonies and in the 'long form', i.e. the full set of readings specific to this day. It was accompanied by the Schola Abelis of Oxford with chant.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.