Chairman's Blog

Photos from the Family Retreat

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Is Mass in the vernacular inaudible?

In the Catholic Herald of 18th March, Ann Widdecombe suggested that it frequently is: so much so, that with the withdrawal by her parish priest of sheets with the proper prayers and readings printed on them, she has resorted to using a hand missal, as have many others in her parish.

There have been a lot of complaints from liberals about the unintelligibility of the vocabulary of the 2011 English translation, which contains hard words like 'ineffable', 'venerable' and 'contrite', but Widdecombe's difficulty is a separate issue entirely. She wants a printed text to look at because she can't understand badly read or heavily accented lections, mumbled psalms, or words overlaid with the crying of babies. (Her article is not on the Catholic Herald website, but on the right is the money quote.)

We can all sympathise with Widdecombe's problem, but her solution suggests something very strange and very un-liturgical: a group of people simultaneously reading a liturgical text is no-one idea of a common act of worship. The problem has arisen because, odd as it may seem, putting the liturgy into the vernacular has not made it accessible to the congregation, even when it is the congregation's own vernacular. If people feel the need to follow the text in a printed form, then they might as well be hearing the Mass in Latin.

Widdecombe is right: it is quite difficult hearing and understanding a text being read out. I had a formative experience as a graduate student attending a small academic conference, where the speakers used the complete range of approaches to giving their talks: from the word-by-word reading of a text, at one extreme, to the complete ex tempore experience. It became very clear that, in reading a text, the modulations of the voice, so important to make spoken English readily intelligible, tend to be flattened out. This is less so if the text is very familiar, or even learnt off by heart, but this still doesn't come out in a conversational way. A carefully prepared, but note-free talk from the energetic American ethical theorist Brad Hooker was positivly electrifying, by comparison with many other presentations. The trick was that he knew exactly what he wanted to say, but hadn't selected the words and phrases in advance: he was just telling us his ideas, as he might have done in the course of an animated conversation.

|

| Douglas Adams' permanently depressed robot, Marvin. |

Such an approach is of course impossible for readers in church, and as different from a liturgical experience as can be imagined. This contrast, however, between how readily we can grasp the meaning of ex tempore speech, and the more solemn proclamation of venerable liturgical texts, has not been sufficiently taken into account in the debate about 'having the Mass in English'. A lay reader at Mass, with little or no training, who may never have seen the text before and may have difficulty understanding it at first glance (no shame there, of course), straining to avoid the smallest error in reading it out, is predictably going to sound as enthralling as Marvin the Paranoid Android. Give the poor lector an unfamiliar accent and a little stage-fright and, yes, the congregation will be reaching for their little sheets or missals.

What if the reader is highly trained, and manages to inject the text with suitable solemnity? This is likely to obscure the meaning in a somewhat different way. Again, conversational modulations of the voice will be flattened out, this time on purpose: you don't actaully want the Epistle to sound like a racy story told in the pub. Before we get too excited, like Ann Widdecombe, about how well the Anglicans do it - or once did - bear in mind that they had two huge advantages: a semi-professional cadre of lectors (the Parish Clerk et al.: no chance of it being a form of liturgical participation for the ordinary pew-sitter), and the ancient, one-year Lectionary, (almost) identical in the Book of Common Prayer and the 1962 Roman Missal. The familiarity of the readings makes it possible to undertand them even if they are read in a somewhat stylised way. Or, for that matter, in Latin...

So, remind me again, what exactly was the point of having the Liturgy of the Word in the vernacular?

The advantages of Latin are many. First, it makes possible the use of the ancient tradition of chanting the text, which is a major aspect of the Latin Church's musical patrimony, one which has been unjustly taken away from most Catholics. Again, whether sung or said, a Latin text is equally possible for people of any language to follow: if they want translations into their preferred language, whether Polish or Irish, they can have them. If they are going to equip themselves, like Ann Widdecombe, with a hand missal, for major languages they can even choose their own translation in the Extraordinary Form, since unlike with the Novus Ordo a hand-missal is just an aid to devotion, not an official liturgical book tied to whatever version of the vernacular lectionary the local bishops have adopted.

Yes, hand missals for the EF can be revised and updated without the agreement of the entire English-speaking (or Francophone, or German, or whatever) world. As a matter of fact, the effort to approve a new version of the English Lectionary was abandoned in 2014, becuase of the difficulty of getting everyone to agree about it. OF Mass-goers are going to be listening to the long-superceded, 1966 'Jerusalem Bible' version, justly derided for being a translation not from the ancient languages but from French, for many years to come.

But above all, the use of Latin for the lections serves to make the point that the whole of Mass is an offering to God: as Vatican II said, the whole of Mass is a single act of worship (Sacrosanctum Concilium 51). It is misleading to imagine the Liturgy of the Word as didactic (teaching) rather than latreutic (worshipping): all parts of the Mass contain texts edifying to the Faithful, but all are in the service of God, in praise and thanksgiving. It is part of a sacred time, and the use of a sacred language is appropriate. Perhaps if this reality was more vividly presented to Ann Widdecombe's fellow parishioners, they wouldn't be quite as keen to keep their noses in a book while the Holy Sacrifice is taking place just a few feet away from them in the Sanctuary.

But then, with more than a dozen Eucharistic Prayers to choose from, is there any part of the Ordinary Form Mass with which they could even gain the kind of easy familiarity regular worshippers at the Extraordinary Form take for granted? It must be conceded, contrary to Widdecombe, that the whole construction of the OF assumes that the Faithful will be able to understand everything instantly as they hear it, and indeed seems premised on the assumption that this not only makes possible the use of a wider range of texts, but that this choice is a useful antidote to boredom.

On the last point, they may have over-estimated the degree of excitement yet another 1960s-era liturgical text or Scriptural translation is capable of eliciting.

See the Position Paper on the Proclamation of the Lections in Latin in the Extraordinary Form.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Photos of the Easter Vigil at St Mary Moorfields

I was present myself at this and these are my photos. There was a terrific rainstorm halfway through the service, but we managed to get through the Holy Fire part of the service with just a little drizzle.

St Mary Moorfields was packed, which means upwards of 200 people were present.

A big 'thank you' is needed for the clergy, under Fr Michael Cullinan, servers and singers for all the very demanding services of the Easter Triduum: three sets of Tenebrae and the three major services of Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Vigil on the Saturday. For these Richard Picket was an expert MC. Matthew Schellhorn with his Cantusy Magnus provided wonderful music for all of them. Our most ambitious set of Triduum services to date was also the most successful and the best attended.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Photos of Good Friday at St Mary Moorfields

The full set of Good Friday photos here.

It was organised by the Latin Mass Society and celebrated by Fr Michael Cullinan.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Public Masses at Prior Park during the Priest Training Conference

The chapel at Prior Park is stunning; anyone in the area should take the opportunity of the LMS Priest Training Conference to attend of the public Masses taking place there next week.

Monday 4th April: 5.00pm Solemn Mass of the AnnunciationTuesday 5th April: 11.00am Mass of Vincent FerrerWednesday 6th April: 11.00am Solemn Requiem MassThursday 7th April: 11.00am Solemn Votive Mass of OLJC In addition to these, there will be Vespers and Benediction on Tuesday 5th at 5.00pmSupport the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Recent Photos

Benediction in Passiontide in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford.

Tenebrae in St Mary Moorfields, on Spy Wednesday.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Surrexit! He is risen.

From the Rosary Walk at Aylesford Priory.

From the Rosary Walk at Aylesford Priory.

Happy Easter!

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

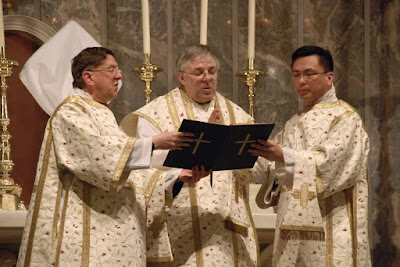

Maundy Thursday in St Mary Moorfields, London

With Canon Peter Newby, assisted by Fr Michale Cullinan and Fr Cyril Law.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Stations of the Cross: new short video from the LMS

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Triduum Recess

Jesus is laid in the Tomb,From a series of plaques depicting the Seven Sorrows, at Carfin Shrine, near Glasgow.

Jesus is laid in the Tomb,From a series of plaques depicting the Seven Sorrows, at Carfin Shrine, near Glasgow.

Wishing my readers a holy Easter Triduum, and the joy of the Resurrection.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.