Chairman's Blog

Masses of Reparation in Oxford and London

I'm happy to announce not only a Mass pro remissione peccatorum (for the remission of sins) in Oxford, but also one in London.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Anyone know the late John Arnell?

See the full story.

'Desperately' is not quite the word I'd have chosen, but we really would like to give any friends and acquaintances the chance to attend a Requiem for him in the most appropriate location possible, and it would be really nice to know something about him. We've tried some obvious avenues without success and now we've got the story into a local paper.

The bequest he has left us is not life-transforming for the LMS, but it is really, really nice and as the story says it is the largest single bequest we have ever received. This is particularly touching since Mr Arnell was not a man of great wealth: much of the money is simply the modest flat he owned and died in. Since there are no close relations, or friends acting as executors, it behoves us to ensure he is given a proper public send-off. (We have, of course, already organised Masses to be said for his soul.) It is upsetting that we weren't notified before the solicitors dealing with the case had body cremated... but we'll do what we can.

Anyone with informtion should email info@lms.org.uk

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Friday 15th June: Mass of Reparation for abortion, Oxford

|

| Mass for the Epiphany in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford |

There will be a Sung Mass in view of the Irish Referendum result:

Friday 15th June, 6pm

SS Gregory & Augustine's,

322 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 7NS

(click for a map)

The Mass Sung in the Extraordinary Form, with Gregorian Chant provided by the Schola Abelis of Oxford.

It will be the Votive Mass pro remissione peccatorum: for the remission of sins. The Mass texts acknowledge our sinfulness and our need for forgiveness, our dependence on God's mercy and our confidence in His goodness.

It will be celebrated by Fr John Saward, Priest-in-Charge of St Gregory's.

The church has a car park.

Friday 25th June: Mass of Reparation in Oxford

|

| Mass for the Epiphany in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford |

There will be a Sung Mass in view of the Irish Referendum result:

Friday 25th June, 6pm

SS Gregory & Augustine's,

322 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 7NS

(click for a map)

The Mass Sung in the Extraordinary Form, with Gregorian Chant provided by the Schola Abelis of Oxford.

It will be the Votive Mass pro remissione peccatorum: for the remission of sins. The Mass texts acknowledge our sinfulness and our need for forgiveness, our dependence on God's mercy and our confidence in His goodness.

It will be celebrated by Fr John Saward, Priest-in-Charge of St Gregory's.

The church has a car park.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

A pro-life appeal: Making the best use of our misfortunes

The best use we can make of a hideous, painful, and morally outrageous event like the Irish referendum result is repentance. Private repentance is always positive, but I would myself like to do something with a public manifestation, and to do this in collaboration with others, if anyone is interested.

It is a truism to say that penance is undervalued in the Church today. There is something amiss when one sees in the texts of the liturgy references to 'our fasts' and 'our mortifications' on days when no fasting or mortification is any longer required by the Church: this was the case on Saturday, the Ember Saturday of Pentecost. It is not just a matter of the dramatic cutting back on fast days since Vatican II, and not even the excision of references to sin and penance in the Novus Ordo, however: the problem goes further back, and penetrates the Church more deeply.

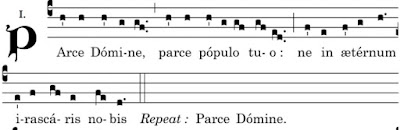

In any case, without changing the discipline of the Church (which I can't do) I would like to encourage priests to use the options which exist to express the Church's penitential imperative. For example, as the Latin Mass Society's Ordinary Prayers of the Traditional Mass notes, in Benediction the pre-Conciliar books permit and encourage the invocation 'Parce Domine' after the Collect 'Deus qui nobis' ('O God, who in this wonderful Sacrament...'), before the Benediction itself. You can say, three times:

Parce, Domine, parce populo tuo, et ne in aeternum irascaris nobis

or in English:

Spare, O Lord, spare thy people, and be not angry with them for ever.

Or sing it:

In addition to this, and for laity as well as priests, I have an idea, or the seed of one, for which I'd like to test wider support, of organising two (sung, traditional) public Masses a year in reparation for abortion and other manifestations of the culture of death.

One would be a Votive Mass of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which is celebrated in the USA on December 12th (and for that reason can be celebrated anywhere as a Votive Mass). Our Lady of Guadalupe, who is Patron of the Americas, has very appropriately been adopted by the Pro-Life movement as her miraculous image is of her during her pregnancy. I would ask for this to be celebrated on or close to her feast day.

The other would be a Votive Mass pro remissione peccatorum ('for the forgiveness of sins'), one of the Votive Masses found in the 1960 Missal. To give a flavour of the texts, the Gospel of this Mass is Luke 11:9-13, 'Ask and you shall receive'; the Gradual is Ps 78: 9-10: 'O Lord, forgive us our sins: Lest they should say among the Gentiles: Where is their God?' I would aim to have this celebrated at the other end of the year, in June: so, quite soon.

As the Representative of the Latin Mass Society in Oxford area, and the manager of a chant schola, it is a fairly simple matter for me to ask one of our many excellent priest supporters in the area to celebrate these Masses, to arrange chant accompaniment, and to advertise it locally. The cost would be minimal. However, if there is real support these Masses could be celebrated with more solemnity, with solemn ceremonies, with polyphony, in London, or in multiple locations.

Each celebration of Mass has infinite intrinsic value. This means that two Masses do not have greater value than one. The reason we have multiple Masses celebrated for an intention is because in addition to the intrinsic value of the Sacrifice of Calvary which is re-presented in the Mass, there is the 'extrinsic' value of a Mass, the value of its prayers and the prayers of those who attend it. It is in this sense that we say that a Mass celebrated with reverence is better than one with abuses; a Mass celebrated with greater solemnity is better, in this sense, than one with less; many Masses, involving many different people, are better than just one.

The principle reason for suggesting two Masses a year for this intention is to keep the cause in our minds, our hearts, and our prayers. I know lots of people do lots of things with this purpose: in England an outstanding example is the Rosary Crusade of Reparation in London, a procession from Westminster Cathedral to the London Oratory. I would like to add to these existing initiatives something which represents the specific contribution the Traditional movement, and the network represented by the Latin Mass Society, can make.

I'll make a start with this idea locally and quietly but if there is wider support I'll make more of it in the ways I noted. In particular, if Masses are to be said with professional choirs financial contributions will be needed, and if they are to be said in additional places, more people will have to take on the organising.

If you'd like to help email info@lms.org.uk with 'FAO Joseph Shaw' in the subject line.

Photos: Whit Saturday Mass celebrated in Holy Rood, Oxford, by Fr Daniel Lloyd, with Solemn ceremonies and in the 'long form', i.e. the full set of readings specific to this day. It was accompanied by the Schola Abelis of Oxford with chant.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Ireland turns to Moloch

John Stuart Mill wrote that the freedom of a liberal state should be considered as the freedom to do anything which does not harm others. The doctrine sounds reasonable until you realise that the people who profess to live by it manipulate the term 'harm' in such a way that whatever they don't like counts as harmful, and whatever they do like does not count as harmful. The doctrine of the modern world, which Mill was attempting to put into respectable dress, is that in order to be free, in order to enjoy life properly, one must be able to inflict indescribable suffering and even death on others. To be free one must be able to abandon one's spouse and walk out on one's children; one does not need the right to quote the Bible in a street conversation, or wear a religious habit on the beach. Calling a person by a grammatically correct pronoun is a harm; killing an unborn baby is not a harm.

This may seem confusing but it makes sense really: there is a pattern. The things you are able to do, and indeed must be able to do, are the things necessary for a group of highly specific lifestyles. The things you are not allowed to do are the things which impede or complicate those same lifestyles. It is not that the favoured lifestyles are happy ones: studies of objective life-outcomes like mental health and suicide rates may even rate them poorly compared with alternatives not so beloved of our political elite. This does not prevent this conception of freedom from condemning actions which might facilitate a person's move from the former to the latter. For what is true at the individual level, that freedom consists in being able to harm others, is true at the social leval as well. A free society, on this view, is a society which harms whole groups of people: a society which insists that they remain in a state of misery. The worst thing anyone can do is to help those in a homosexual lifestyle, women in crisis pregnancies, or children who are being abused by rape gangs: any of these who actually want to be helped. No: society has decreed that they are free, that freedom demands that they follow a narrowly defined path which predictably leads to objectively catastrophic outcomes, and that they must continue to suffer until they die.

It amuses me, in a meloncholy way, to read criticisms of 'integralism', a term which is used to describe what in Political Theory is called a 'perfectionist' theory: a theory that the state should act on a view of what leads to happiness and what does not. The alternative is supposed to be a 'neutralist' theory. We are living in an integralist society, my friends; just not a Catholic one. The ways of life which are given special status in our society, which are encouraged and protected, have not been chosen on the basis of Catholic principles. They appear to have been chosen on demonic principles. They have nothing to do with what any sociological researcher would class as 'good outcomes'. They are our society's offering to Moloch of the lives of our children and young people. It is considered virtuous to make this offering; it is impiety to refuse it.

First Moloch, horrid king, besmeared with blood

Of human sacrifice and parents' tears,

Though, for the noise of drums and timbrels loud,

Their children's cries unheard, that passed through fire

To his grim idol. (link)

I have few words of comfort for the defeated pro-life campaigners in Ireland. I write before the official results have been announced, but by all accounts the margin is not such as could have been overcome by a slightly cleverer campaign strategy. I don't think they need blame themselves. They were battling something bigger than the usual political movement. Their position was an impossible one, with the self-destruction of the Catholic Church's moral authority in Ireland coupled with an international movement in favour of death.

We aren't now faced with a referendum campaign, but a lifetime to live with the consequences of the series of Molochian triumphs in Ireland, Britain, and beyond. What are we to do? We are called on to oppose injustice as best we may; to help our neighbour as best we may; to worship God as best we may. I will make only two observations about the form this must take.

One is that the big issues will not come right without a conversion of heart on the part of a large number of our fellow-citizens. Personally, I love clever arguments, but while we have to have them the heavy lifting is going to be about making an integral Catholic life seem both attractive and possible to people. Only the fullness of truth, liturgy, culture, and God's grace, is going to work here.

The other is that the work we can do for the forseeable future is going to be only preparatory and experimental. This will have its value of course, but we aren't going to make substantial progress until another condition is met: the restoration of the credibility and evangelising effectiveness of the hierarchical Church. There is very little, if anything, we can do about that as lay Catholics, or even as priests, but no Catholic movement to infuse the temporal sphere with the values of the Gospel (as Vatican II expressed it) is going to make headway without the support of the Pope and a good number of bishops. A certain proportion of ineffective or even corrupt bishops would not necessarily stop it, but a good Pope won't be effective if a vast body of bishops is against him, and good bishops can do little if the Pope is against them.

Right now it doesn't seem very likely that this condition will be met in my lifetime, but you never know.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Bishop Schneider's Mass in London: photos

St Mary Moorfields was packed to the doors last evening for Bishop Schneider's Mass. There was hardly room to stand at the back and the coridoor leading to the church from the street was occupied as well.

The sanctuary was also full to capacity. The Assistant Priest was the LMS' National Chaplain, Mgr Gordon Read, assisted by Fr Mark Elliot-Smith as Deacon, Fr David Evans as Subdeacon, and Canon Vianney Poucin de Wouilt ICKSP as Clerical MC.

Beautiful music by a number of English Catholic composers - Taverner, Tallis, and others - was sung by Cantus Magnus, directed by Matthew Schellhorn.

Bishop Schneider preached about the coming of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost at Mass, and after Mass gave a talk about the Church Militant, and the idea of Christians as soldiers of Christ. The basement of the church, where the talk took place, was similarly packed to the doors, and beyond.

Mass was offered for the Irish Referendum.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Ember Saturday Mass in Oxford

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Dominican Vigil of Pentecost: photos

Last Saturday the Dominicans of Oxford celebrated the Vigil of Pentecost according to their ancient books, which means that the Mass proper is preceeded by four Old Testament readings. It was accompanied by the Schola Abelis of Oxford. The celebrant was Fr Richard Conrad.

Pentecost is one of the great festivals of the Church's year. Perhaps because it falls on a Sunday, I think we tend to take it for granted. But it's ancient Vigil, which reprises the Vigil of Easter, and Whit Week which follows it, once made it stand out. As well as the subsequent sequence of Sundays being called the 'Season after Pentecost'.

An unexpected feature of the Mass on Saturday was the presence, in the congregation, of a number of members of the Council of the Association for Latin Liturgy, who happened to be having a Council meeting in Oxford later in the day. The ALL broke away from the Latin Mass Society in 1969 when some members wanted to promote the Novus Ordo in Latin, but we enjoy friendly relations with them today.

Liturgy has to be experienced, not read about; photographs and recordings can give only the vaguest sense of what it is like.

I feel there is something especially serene about the Dominican Rite, and the chants have a distinctiveness which gives them (to those used to Roman chants) a slightly unexpected, even weird, quality which makes them fresh. I noticed this particularly with the Litany of the Saints which, though very simple, required constant effort on the singers part if it were not to turn into the Roman version. It was a privilege to assist at this Mass.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Cardinal Castrillon Hoyos: RIP

Cardinal Castrillon Hoyos died yesterday. He deserves our prayers.

He was President of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei over the period of the promulgation of Summorum Pontificum, obviously a very important time for those attached to the Traditional Mass.

In the photograph below, he is blessing delegates at the Foederatio Universalis Una Voce during the General Assembly of 2013; below that he is celebrating Mass for them in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel of St Peter's in Rome in 2011. That was the first time a Cardinal has celebrated the ancient Mass in St Peters since the liturgical reform.

There is an obituary of him on Rorate Caeli.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.